What would you do if you knew you had 10 seconds before an earthquake hit?

Robert de Groot, a U.S. Geological Survey spokesperson in California, can name a few things. Dentists can stop drilling. Teachers can tell their students to get under their desks.

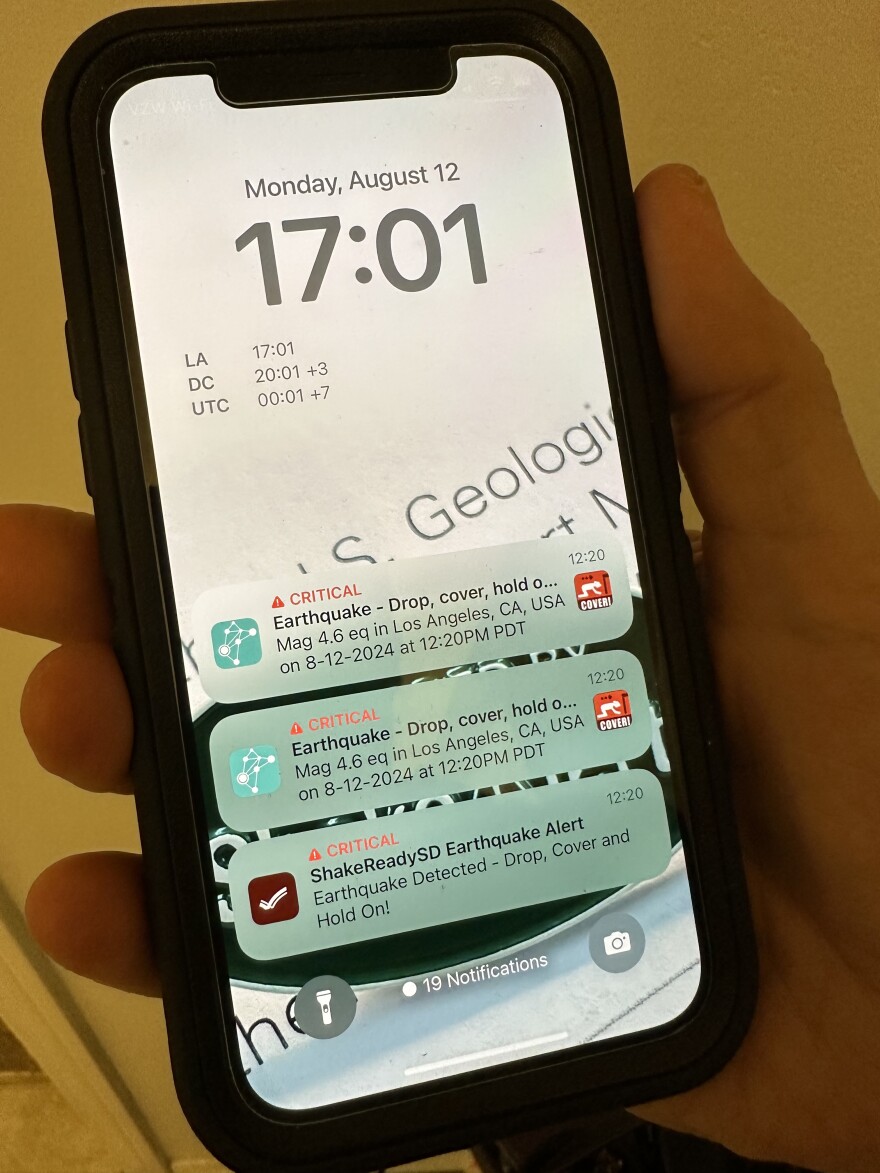

"People can take protective action," he said. "Slow down that train, open that firehouse door so first responders can get their vehicles out — or drop, cover, and hold on."

Once, de Groot said, he was in the middle of an acupuncture appointment when he got an earthquake alert.

"I actually had to protect myself, and also respond to the earthquake itself," he said. "While this is all going on, I had, like, 35 needles in me."

De Groot works with the USGS to develop and expand an early earthquake warning system called ShakeAlert. It tells people an earthquake is on its way, usually in the form of a text message.

Since 2021, the system has been available to over 50 million people in California, Washington and Oregon. Mexico started implementing a similar system decades before the United States. And Canada's went live last year.

But nothing like it exists in Alaska, which gets more earthquakes — and far more big earthquakes — than any other state.

Alex Fozkos is a graduate student with the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute. He's one of the scientists working to find out what it would take to establish an earthquake early warning system here.

"It hasn't really entered into the public's general awareness," he said. "One of the main goals of this study is to have a set of numbers that we can go talk to people about and say, 'Hey, would you be interested in this?'"

It's not science fiction, and it's not earthquake prediction — it's all about early detection

An earthquake releases a lot of energy, which travels through the ground in two main types of waves. The first is called a P wave.

"Those are fast waves," said Fozkos. "But they're not very strong."

If Alaska had an earthquake early warning system, it would rely on sensors close to the earthquake to pick up those fast-moving P waves and relay that information to the Alaska Earthquake Center in Fairbanks. The system would then create an alert with an estimate of how strong the shaking could be.

Many people could get that alert before feeling the potentially damaging S wave.

"Those waves are slower, but they're a lot stronger," said Fozkos. "They usually bring the strong ground motion."

Alaska's most recent big earthquake was July's magnitude 7.3 earthquake off Sand Point. Fozkos said his analysis shows that an early warning system could have given Sand Point more than 10 seconds of lead time before the worst shaking. King Cove could have gotten about 20 seconds.

But there's a huge financial barrier to getting the system up and running in Alaska.

For it to work, Fozkos said, the state needs more earthquake monitoring infrastructure.

"A lot of the stations are out in rough, remote areas," he said. "The winters are very cold and harsh, and we have to do a lot of maintenance on stations to keep them up and running. So that, combined with just the size of Alaska, we need a lot of stations and a lot of coverage for a functional early warning network."

It would cost about $66 million upfront to bring an earthquake early warning system to Alaska. Maintenance could be another $12 million a year. Fozkos said the federal government would have to foot the bill, unless private partners want to chip in.

Scientists are still optimistic

USGS spokesperson de Groot said third parties have already stepped in to help the system in California.

"We produce the data, and then we work with third parties, like Google and others, to actually deliver alerts to cell phones," he said. "I help build relationships with those third parties to take our data and use it to keep people safe."

State Seismologist Michael West, with the Earthquake Center, is in charge of the project to map out the future of ShakeAlert in the state. Despite the financial and logistical hurdles, he said he knows it'll get here, he's just not sure when. There's no federal or state funding to implement the system in Alaska, and no corporate funders have offered support.

"It is not an 'if' question, because that's just where the world is moving," he said. "At some point in our future, early warning will be something that we all just take for granted as one of those public services that exists."

Copyright 2025 KUAC