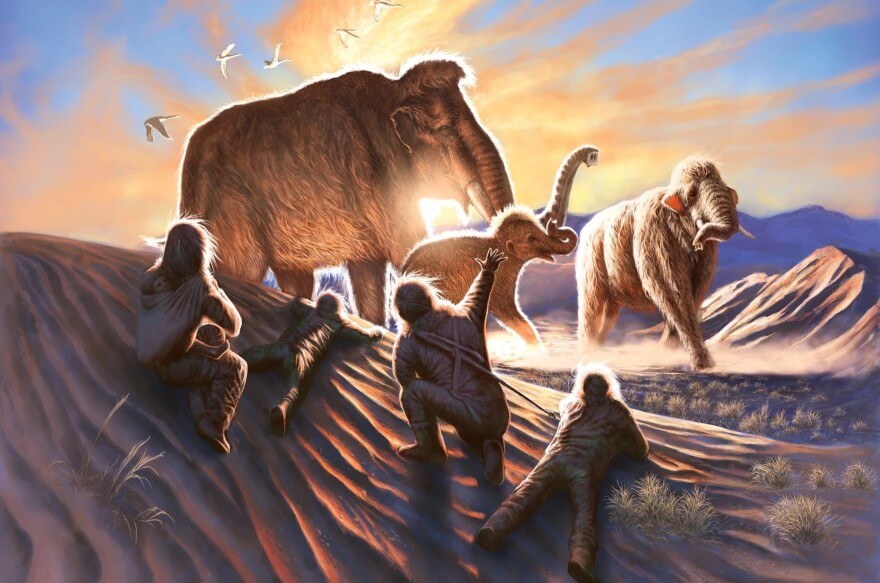

The first Americans ate a lot of mammoth about 13,000 years ago, after entering through Alaska to rapidly populate North America.

That's according to a study co-authored by researchers at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and published in the journal Science Advances.

By analyzing the isotopic data from the remains of a child, who was part of an ancient group called the Clovis people, the researchers got the first direct evidence that ancient Americans focused on hunting large animals. That often included the now-extinct wooly mammoth.

UAF archaeology professor Ben Potter is a co-lead author of the study. And Potter says the Clovis people's adaptation to hunting mammoths was a unique and powerful advantage.

Listen:

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Ben Potter: They were megafaunal specialists, these earliest Americans, Native American ancestors. They focused on megafauna, and particularly Mammoth, and that allowed these people to be so successful, to expand rapidly into Beringia, from Asia, into our part of the world, through Alaska, and then expand throughout all of the Americas, and in basically a few hundred years. So it was a very successful adaptation. And we were always wondering what facilitated that, what made that happen?

So what hunting mammoth allows you to do is, once you understand the ecology of that animal, it allows you to successfully follow them, follow these herds. And we know they were very migratory, and they travel long distances, and you don't need to necessarily learn each valley you move through. Like in a more recent foraging perspective, you want to look at the fishing, maybe shellfish, salmon, small game birds, things like that. You can't transfer that knowledge very well from, say, Alaska to Alberta to Mexico, for instance, whereas mammoth are found in all three of those places. And this, we think, is sort of the smoking gun that allows us to understand that adaptation.

Casey Grove: Yeah, that's super interesting. And maybe we could just back up, our understanding of this was mostly based on finding old tools or the remains of prey animals. But like you said, we actually know now that this is exactly what they were eating. But how do we know that?

BP: Sure, there's a couple of answers. But first, I want to sort of highlight what you just said. There's debate. There was debate. It wasn't just that these are indirect clues. There was actually hotly contested arguments on both sides that — at the level of how do we understand ourselves as hunter gatherers in the ancient past — there was a lot of literature on both sides saying, "No, they couldn't possibly have done this." And then others saying that, "Yeah, the evidence suggests that they did." So that's where we came into this debate was, you know, very much trying to address this with direct data that can hopefully resolve some of this.

So it's important to think about how our bodies are made of elements. The animals are made of elements. Like carbon and nitrogen are very common elements within our body. And we build our tissue through the food that we eat. And so each element has some varieties of isotopes. These are just, they're slightly different masses, because they have different numbers of neutrons. So carbon-13 versus the normal carbon-12. Nitrogen-15 versus the normal nitrogen-14. So we look at the ratios of those two stable isotopes with respect to different plants, with respect to the animals that eat those plants, and they're very distinctive for each species. Different foods have those different signatures.

And so that's what we did. We have the only known Clovis burial, actually the only known human associated with the Clovis culture. This was a child, 18 months old, in southern Montana called Anzick-1. And what we do — we didn't do any destructive analysis — we relied on a couple of samples that had been taken previously. We used those isotope samples. We did a quick nursing correction to get back to the diet of the mother, so we're looking at the maternal diet. And then we compared her values to the values of other species that we gathered together for the region, which is the northern Great Plains, and for the time period, which is the last bit of the Ice Age. And from there, we could then produce statistical models to identify what proportions of these different foods were in her diet. Not just mammoth, but 96% of her diet was on megafauna, so very high elk content, also bison. And small mammals are very negligible. Less than 4% of her diet was on small mammals, like rabbit, hare, marmot, things like that. And what we found was that her diet was most similar to homotherium, and that is the Scimitar Cat. So it's a variant of Saber Tooth cats that were alive in the last Ice Age. So our individual, our Clovis female, was most closely similar to this hyper-carnivore that focused on mammoth. So again, more evidence for this heavy-mammoth diet.

CG: So the Scimitar Cat has, my understanding is, large teeth, like saber-like teeth, I guess. And we had some idea of what sort of tools people were using back then, because we have been able to find them. But why was there debate about whether or not they could successfully hunt mammoth? Is it because the tools were small? Like, obviously we don't have giant saber teeth. But why did people think that that wasn't possible?

BP: Yeah, it's a long and complicated story. There's different lines of evidence that get really, it gets a little bit complicated. One line was arguing that, "Well, maybe when we look at the animal bones in these sites, only the big-bodied animals, the big bones, survive." They're very dense, and maybe there's a whole bunch of small game, like birds, small mammals, that those just simply didn't survive. So we're missing those in the record. That was one argument.

Other arguments sort of rely on, if they were really hunting megafauna, we should see tons of kill sites, and we only see like 15. So that's not enough. So, you know, it goes back and forth. You can sort of pin your hat on on either side, but ultimately, this is the direct data that's really required to answer that question

CG: Well, so I guess the 18-month-old Clovis child that is at the center of this, it was found in Montana, I think you said, and I read that an important part of this was interfacing with the Indigenous people in Montana and I guess Wyoming also. Can you tell me how that went?

BP: Yeah, and Idaho as well. So the work that I've done for the last 30 years up here in Alaska has always included consultation with local Indigenous peoples. It's not only ethical, it's actually just really good science, because there's going to be a lot of traditional knowledge that are going to be connected to our interests. We certainly want to understand how people interfaced with modern conditions in these areas. And also it's just the right thing to do, when we're when we're talking about people's heritage.

And so when I first became involved in this project, that's one element that I really wanted front and center, is that we reached out to tribal liaisons and identified who should we talk to, who's interested in this material, what questions do they have? What questions can we address? And I think it's been very productive discussions, very, very positive relationships that are developing based on this research. And I'm happy to say, you know, this was done through no new destructive analysis. So that's really important to Indigenous peoples in that region, that, you know, we're not destroying the remains. The remains are safely reburied. They were reburied in 2014, and we can still generate new information, significant information, about the heritage of their ancestors in a meaningful way, moving together, the scientists and the Indigenous peoples.

CG: Yeah. And it seems just kind of cool, too, to like make this connection to somebody that lived in their region, that is an ancestor of theirs, that they can look at and say, you know, "That was us," right?

BP: Yeah, and I think, you know, understanding that this, the Clovis people, were unique. They were very good at what they did. They were, by any stretch of the imagination, very successful. So they were able to expand genetically, to understand this is, for a fact, sort of ancestral. The mother is clearly related broadly to all of these people. And I think that's some of the pride that I've sensed in talking with a number of people, Indigenous folks down there, is that, yeah, they're able to handle, easily, the most dangerous, largest animals out there in the last Ice Age, and this was an effective strategy. It was a smart thing to do, and they could easily do it.

CG: Well, you know, other than being just completely fascinating, how does this research inform modern humans? I mean, in terms of either, you know, our adaptability, what things we might expect from climate change, anything like that?

BP: Oh, there's lots of lessons. So I think one of the fascinating things about the region that I study, and that is related to the work that we did on this project, is the transition from the last Ice Age into the modern Holocene period. It was a period of rapid climate change, lots of temperature shifts, vegetation shifts, and of course, animal populations were greatly affected. That was the last time we've had a great warming within the Earth's climate. And so we certainly can directly look at modern and future global warming trends. And so it really behooves us to understand those ancient systems so we can begin to model, and better model, and more realistically model, the things that are going to be in store for us in the future. Another issue is how unique this situation is, this major expansion from one hemisphere to the other hemisphere. You know, this is the origin. This is quite early, and we need to understand it, our capacity as a species.

CG: Well, Ben, I'm going to invoke an old Sesame Street thing that they did that was called, "Would you eat it?" I suppose if you were a Clovis person, you wouldn't have a whole lot of choice, you'd probably just be happy to have some mammoth. But I wanted to ask, do you want to guess as to what that might have tasted like?

BP: Well, first, I would absolutely eat it. I think would be tasty, especially if it's fat-rich. You know, that's where the taste is at. What do I think it would taste like? It probably would be similar to Asian elephant. That's the closest modern species to mammoth. But I've never tried elephant, you know, of course, it's not in regular supply. And yeah, so I wouldn't, I'm not going to go with the chicken example. I don't know what it would taste like, but it would probably be good. I would suspect it would be good. Yeah.