The number of incarcerated Alaskans released on discretionary parole last year dropped to its lowest rate in at least the past decade, according to data recently released by the Alaska Parole Board.

Only about 16% of inmates who applied for discretionary parole were released in 2020, down from a high of 66% in 2015.

“Looking back historically, we’ve not seen this before,” said Jeff Edwards, director of the Alaska Parole Board.

It may have something to do with changes to the law, he said.

Senate Bill 91 — a criminal justice reform bill which passed the Alaska Legislature in 2016 — required the board grant parole in certain cases, Edwards said. But a new law, House Bill 49, which went into effect in the middle of 2019, gives more discretion to the board.

“There was a legal requirement in some cases, where if inmates met those requirements that the board ‘shall’ grant discretionary parole. And that has since been changed under HB 49 to that the board ‘may’ grant it,” he said. “And just the difference between ‘shall’ and ‘may,’ in legal terms, is quite significant.”

Another possible factor behind last year’s low rate of parole approval, Edwards said: The pandemic-related cancellation of in-person rehabilitation programing, often a requirement for parole.

“The department did the best they could — they tried different avenues and frequencies to make sure that the programs were up and running,” he said. “But that was one of the questions and discussions that came up quite often, was about the availability of programming.”

But advocates are concerned there are other reasons the rate of granted paroles dropped so sharply last year.

Megan Edge, spokesperson for the ACLU of Alaska, said data shows the current board, chaired by the mother of a murder victim, has voted more to deny people up for parole — keeping them in prison longer. She said it’s part of a misguided idea that has been disproved by researchers about harsh sentences for crimes.

“Longer sentences do not make us safer,” said Edge. “Mass incarceration does not equal public safety. We need to be rehabilitating people, correcting behavior and releasing them when they have a chance.”

Edge also points out the low parole rates come at a time when state prisons are already near capacity. The state Department of Corrections plans to reopen a new prison to free up space, but keeping inmates is expensive: Corrections now takes up more money than higher education in the state budget. And denying parole means more people in jail, costing taxpayers more than $50,000 a year for each incarcerated person, according to an estimate from a prison reform research group.

Edge said she’s concerned about a lack of transparency surrounding the parole board’s decision-making, which raises questions about equity.

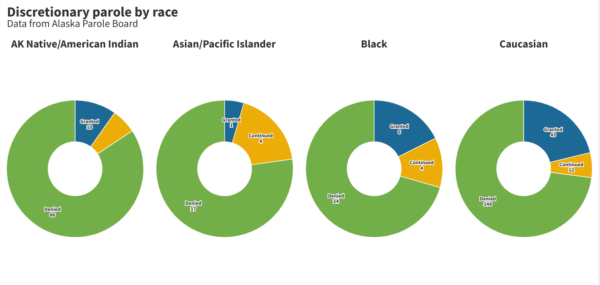

Data from 2020 shows incarcerated white people were about twice as likely as Alaska Native and American Indian people to be granted discretionary parole. The disparity is even higher for people who identify as Asian or Pacific Islanders.

Edge said while other factors could account for the disparity, such as the severity of the crime, the board doesn’t disclose enough data to know for sure.

Ideally, the board would publicly release information including reasons cited for denying parole for individuals, she said. The board keeps the names and case files of inmates confidential.

“We need a lot more information to really understand what’s happening in closed-door parole hearings,” Edge said.

Edwards, director of the parole board, said if there are biases in the parole board’s decision making, legislative auditors can review individual cases. So far, he said, they haven’t deemed that necessary.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated in what year 66% of inmates who applied for discretionary parole were released. It was 2015, not 2016. Also, the story previously mischaracterized how much the state spends on prisons compared to education. It spends more on prisons than it does on the university system, not education in general, as previously stated.

Lex Treinen is covering the state Legislature for Alaska Public Media. Reach him at ltreinen@gmail.com.