State and local law enforcement officials announced a breakthrough on a more than 25 year old cold case in Juneau this summer, thanks in part to a DNA analysis tool at the Alaska Scientific Crime Detection Lab.

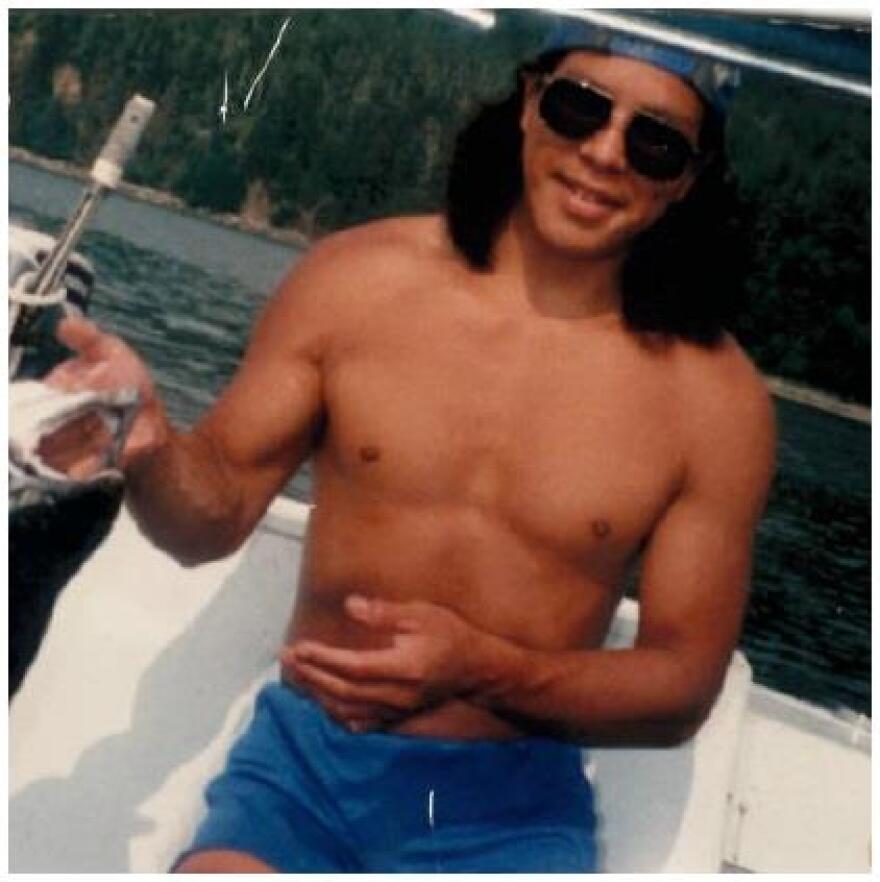

Darryl Bruce Fawcett, an Alaska Native man, was 28 years old when he went missing in 1999. His remains were found by divers in the Gastineau Channel in 2004. In July, with the help of a tool that analyzes DNA from bones, officials said they were able to compare a sample with a family member’s DNA and identify Fawcett.

“It is pretty rare, especially (with) that amount of time to have passed,” said Juneau Deputy Chief Krag Campbell, in August. “So I’m just happy that the family was able to get some closure on this.”

The forensic method is not new, but the Alaska Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory was able to adopt it with new federal grant funding, said crime lab chief David Kanaris. Forensic scientists are able to extract DNA from bones or teeth, which can be compared to DNA of a missing person or relative to make an identification.

Previously, bone samples would be sent out-of-state for testing, usually to the University of North Texas, Kanaris said. The state may continue that practice as needed. “We saw real value in bringing on an ability to do most of the work here in Alaska, where we can,” he said.

Cheryl Duda, a forensic scientist and DNA technical leader at the crime lab, said this forensic method is one of many that investigators use when unidentified remains are recovered.

“For many years now, our laboratory has been able to do testing on a very wide variety of body tissues like blood, saliva, hair roots and skin cells, but all of those are very soft tissue types,” she said. “What is different about this technology that we’re bringing online is it’s a method to extract DNA from bones.”

Duda said that first, any unidentified remains reported to the state go through the Alaska State Medical Examiner’s Office, which determines first if they are human or animal. If deemed human, and a bone or tooth is recoverable, the agency will send a sample to the crime lab for analysis. The DNA is then entered into a national DNA database, the Combined DNA Index System, commonly called CODIS, where investigators can search for a match.

The database can compare the sample with samples of known missing persons, family members, or other samples that law enforcement has collected from crimes or that have been submitted by the public.

“That’s the big first step for us, is generating this profile in the hopes of getting that match or that association in state, so that we can report those results,” Duda said.

Jennifer Foster is a forensic scientist and supervisor at the crime lab, and said that the next step requires coordination across agencies. State employees work with the Federal Bureau of Investigation that governs CODIS, other forensic labs, and local and state law enforcement departments conducting investigations. “So there’s a lot of communication,” she said.

Officials at the crime lab say they’re working on a list of remains to be tested from the Alaska Medical Examiner’s Office, and cases are prioritized as they come into the lab. Once DNA samples are entered into the national database, the search continues.

“So that profile routinely searches every night,” Duda said. “It does missing persons searches monthly. Relatives of missing person searches monthly. So as long as it doesn’t need to be removed for whatever reason, it stays in there and will search.”

Austin McDaniel, director of communications for the Alaska Department of Public Safety, said the state has analyzed three more cases since August, but no identifications have been made.

McDaniel said each case of unidentified remains is prioritized as it comes in through the Medical Examiner’s office, and investigators pursue and coordinate leads for identification. He said the new tool won’t necessarily unlock the state’s cold cases.

“If pulling DNA from bone fragments would have been helpful before, you know, either the crime lab or the medical examiner could have sent that out to other labs to have it completed. So I wouldn’t say there’s, like, this huge backlog of cases that just haven’t ever been worked,” he said.

There are currently 60 unidentified persons cases open in Alaska, according to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons Database, which goes back to 1968. The most recent unidentified remains on that list are bones found in a creek on Aug. 24 in Anchorage.

McDaniel said new DNA samples also get shared with the national database by the public through commercial at-home genetic testing, which can be shared with law enforcement. “That’s usually a box people can check, something like that might happen. Or maybe we go through and have family members reach out to us and offer familial DNA samples that can be compared against,” he said.

McDaniel said local law enforcement investigators can request the DNA analysis as they pursue leads. “An investigator from any number of agencies, not just the Troopers, as they’re trying to go through and maybe work on some of these cases they might go through to reach out to a family member proactively that they suspect might be related to the decedent, and see they can collect a voluntary sample from from them,” he said.

Kanaris, as head of the crime lab, acknowledged these are sensitive cases, especially as Alaska grapples with a crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous people. Alaska Native residents are disproportionately victims of violent crime. At least 27% of the 1,268 known cases on the state’s Missing Persons Clearinghouse database, managed by the Alaska Department of Public Safety, involve Alaska Native people.

“We have worked with the tribal liaisons, understanding that a lot of these bones may come from Alaska Native remains,” Kanaris said. “And so we want to handle these samples as sensitively as we can and be as culturally aware as we can.”

He said another benefit of having this DNA analysis tool in the state’s crime lab, is handling cases more promptly.

“They’re going to involve less transit time. The bones are going to stay in state, and they will, hopefully, be able to be returned to the families for closure as soon as possible. That would be one of the benefits of this,” he said.

“I’d like to see us be able to work as many of the samples, not just with bones, but across the board, with forensic science samples in Alaska, at the Alaska crime lab,” he said. “So I think this is a big step forward for us.”