Should Southeast Alaska have a hatchery-only king salmon sports fishery? Researchers recently tried to answer that question as a possible solution to a declining number of wild kings.

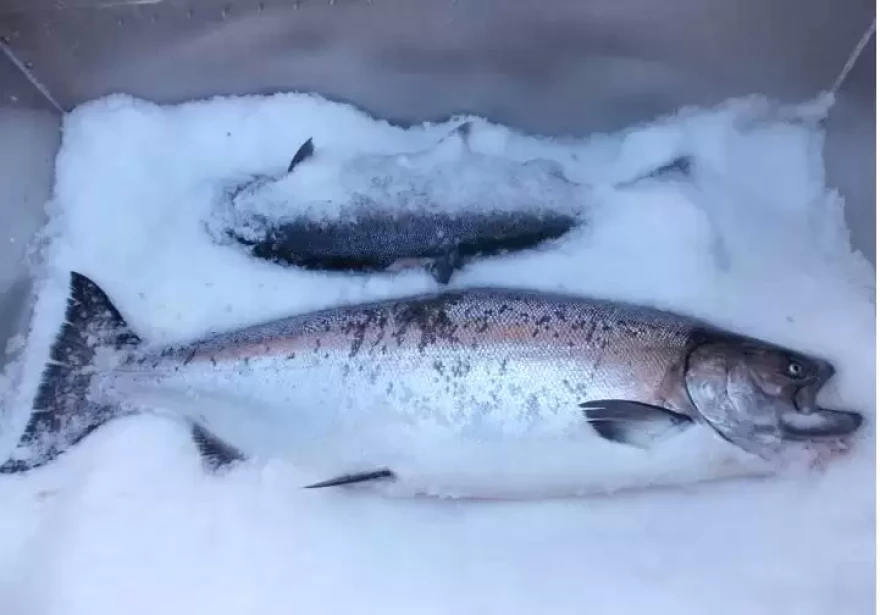

Chinook or king salmon are the largest and most valuable salmon species. They’re sought-after by sport, commercial, and subsistence fishermen alike. But in recent decades, their harvest has become more restricted as populations plummet. A recent study considered if a new Southeast fishery could help – one that allows sport fishermen to keep only hatchery king salmon and release wild ones.

“And an important question there is could this actually be done within the current management context? And is this something that is desirable for folks in Alaska?” asked Anne Beaudreau, who led the study, which took about a year.

Beaudreau is an associate professor with the University of Washington’s School of Marine and Environmental Affairs. The study was initiated and funded by the Alaska delegation of the Pacific Salmon Commission. Members asked the Alaska Department of Fish and Game to explore the possibility of a hatchery-based sports fishery, and the state then contracted with the university.

As part of the study, Beaudreau helped run several public meetings throughout Southeast. Dozens of people participated.

“We heard a lot of concern brought up at these meetings,” she said.

In theory, a hatchery-only fishery – or what’s called a ‘mark selective fishery’ – could provide more sport fishing opportunities. All types of fishing for wild kings are highly restricted because of a treaty that the U.S. has with Canada. It sets harvest limits to make sure that both countries get kings every year. And hatchery king salmon don’t count toward the U.S. treaty allocation.

But the study found that a lot would have to be in place for such a fishery to work. For starters, not all hatchery king salmon in the region are marked. Marked kings have their adipose fin removed, making them easily identifiable. In fact, even a few wild kings in Southeast are also marked that swim to spawn in transboundary rivers leading into Canada. So, in order for a hatchery-only fishery to work, there would have to be buy-in from all the region’s hatcheries. But Beaudreau said some just aren’t set up for marking all of their fish right now.

“The more fish you mark, the more successful you can be in actually implementing a mark-selected fishery,” she said. “It would also require hatcheries to support the idea of mass marking for a mark-selected fishery. And that’s not the case presently.”

Southeast residents also worried about other ramifications – like how such a hatchery sport fishery might affect commercial fisheries. And charter boats concentrating their efforts near hatcheries that locals rely on. And how the management of it might divert resources away from other issues like habitat and bycatch.

Beaudreau said a major concern that arose from the study was incidentally killing wild kings while targeting the hatchery fish. It’s estimated that 16% of catch and release sport-caught king salmon in Southeast die.

“One thing that has risen to the top over and over again, especially in conversations with community members, is these concerns about incidental mortality, the mortality of those unmarked fish that are released,” Beaudreau said.

Also, Southeast’s king salmon fishing is complicated because there is a mix of fish swimming towards many different destinations. Some wild kings are heading to Alaska spawning grounds and others are here temporarily until they return to spawn in British Columbia or the Lower 48. And some are hatchery-produced, returning to where they were released. The fish’s origin varies and depends on the time and location.

Ketchikan sport fisherman Russell Thomas questioned the study’s lack of data on the rate of encountering wild versus hatchery kings.

“It just seems to me like without that information, how do you ever really evaluate what the feasibility is?” he asked at one of the public meetings.

Beaudreau admitted that the study was a high-level overview of the region. Researchers didn’t drill down on how a sport fishery like this could work in specific areas.

Staff from the state’s Sports Fish Division agreed. They said there are too many unknowns right now to start a new fishery in Southeast. Patrick Fowler, a regional fisheries management coordinator, addressed Russell’s concerns.

“I would just say at this time, the Department doesn’t intend to advance a particular proposal,” he said.

But Fowler added that if residents wanted to pursue a local fishery the state department could help gather data for that specific area for a future proposal.