Editor’s note: This story was originally written for the Nov. 22 anniversary of the 1936 landslide. We delayed publication after a deadly landslide struck Wrangell on Nov. 20.

Nearly a day after Juneau’s deadliest landslide, rescue crews had given up hope of finding any more survivors. But they kept working, shoveling muck from atop the 20-foot heap of debris that covered what is now South Franklin Street.

Plumes of steam and smoke billowed from under the jumble of mud, boulders and broken trees. Early that morning, an underground explosion in a buried apartment building had sparked fires that would burn for hours.

Cascades of water poured down Mount Roberts as people sloshed through flooded streets, calling out for loved ones.

A little voice cried out from somewhere beneath the mud. One of the rescuers, an AJ Mine employee named Ernest Mattielli, recognized it as the voice of 3-year-old Lorraine Vaneli, the daughter of his friend Joe.

“I’m tired,” she said. “ Why don’t you come and get me.”

‘Everything went dark’

Nov. 22, 1936 was a quiet Sunday evening in Juneau. It was raining. It had been for weeks.

That night, Lorraine and her parents braved the downpour on their way to a dinner party. As they set out, Albert Shaw was at his grandfather’s house a few blocks away.

“We were reading, my brothers and I — well, I was probably looking at a picture book, at six years of age, ” Shaw said in an interview in November 2023. “All of the sudden, the lights go out — everything went dark.”

Shaw — who has lived in Juneau for all of his 94 years — is perhaps the only living person who remembers that night. But at the time, he didn’t know what was going on.

The lights flickered out at the Matson Boarding House, too, on what is now South Franklin Street. V.A. Babcock, a miner, was finishing up a bath when he heard a loud rumbling. The walls of his bedroom began to twist and tilt.

He covered himself and bolted for the front door only to see the building’s porch get swept away in an enormous flow of mud that roared down from Mount Roberts. He turned back and made a narrow escape by jumping out a window.

Nearly naked in the rain, he stood and watched as the boarding house careened down the hill.

On the street below, a Mrs. J. Wilson made her own narrow escape when “turning around she saw a great concrete building following her, which she described as a huge pile driver, just ready to strike.” Two men pulled her out of the way just in time, the Alaska Daily Empire reported.

Albert Persson and his family didn’t have the time to escape when their apartment on the third floor of the Nickovich Apartment Building started shaking.

“I knew it was a slide. There had been so many before,” Persson wrote in an account published by the International News Service.

He and his wife huddled around their two young children as plaster rained down on them. Then the ceiling and the walls collapsed.

“It was sort of a funny feeling,” Persson wrote. “Like being inside an egg when something smashed it.”

The entire Persson family was rescued alive from the wreckage.

The slide engulfed the Matson House, the Nickovich building and two family homes. The great pile of debris — about 20 feet deep and 75 feet wide — came to a halt against the Juneau Cold Storage building, which stood across from the modern-day cruise ship terminal.

Along the way the slide took down telephone cables and power lines, throwing the city into darkness.

“The mighty cascade of dirt and rock roared down the mountainside on its mission of death, sweeping all before it,” the Empire wrote.

Shaw’s father, a volunteer fireman, joined dozens of men who formed the rescue crews — city officials, police officers, U.S. Forest Service employees and sailors from the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Tallapoosa, which was docked in town.

“They put some of the miners to work, shoveling the muck, because that’s what it took,” Shaw said. “This took several days to get it cleaned up.”

Babcock was among them. He borrowed clothes from a friend and returned to the scene of his near-death. The crews set to work by the light of headlamps and headlights from cars and fire engines, which illuminated a gruesome scene. Live wires sparked fires, and heavy rain kept pouring down as rescue crews started digging.

Twenty-three people were caught in the slide. Some escaped with minor cuts and bruises, others with deeper wounds or broken bones. Gust Erickson, who lost his home, survived “slightly crushed” after his stove slid across the room and pinned him against the wall, the Empire reported.

His wife, Cora, was buried beneath the house’s toppling chimney. She was the first slide victim discovered that evening.

“Tragedy has struck the city,” read a column in the Empire the next morning. “The forces of nature with which we must always battle for existence have overwhelmed the puny human efforts for a moment.”

Fifteen funerals

Fifteen people died in the landslide. It was national news. The Associated Press, the New York Times and local papers from California to New England wrote stories about the destruction.

In the light of day on Monday, people found that other, non-fatal slides had come down across town, one on Glacier Highway and another in front of the Salmon Creek Bridge. The debris snarled traffic for days.

The threat of more slides continued in the unrelenting rain. Hillside homes along Franklin Street and Gastineau Avenue were almost completely abandoned.

It took the makeshift search and rescue crews hours to reach the first slide victims — most were buried deep. The more they dug, the higher the death toll rose.

“All the bodies were cut, bruised and discolored, as if hurled through a mighty grinder,” the Empire reported.

A wisp of a red dress led them to the body of Lucia Hoag, who had been attending a dinner party at the Nickovich Apartments with her family. Hours later, rescue crews discovered the bodies of her husband, James, and her fourteen-year-old son, Forrest.

Later that day, crews reached a gray-haired couple wearing pajamas. They were Hugo and Hilja Peterson, a couple who apparently had been crushed in their sleep.

It took five days to recover all of the victims. Most, it seemed, were killed instantly by the enormous force of the slide.

Local churches held 15 funerals that weekend. After the victims were laid to rest, the clean-up took weeks. Pickup trucks, dwarfed by the massive debris piles, lined up to carry the mud off to different parts of town, or to dump it in Gastineau Channel.

The rain was unrelenting for the rest of the year. A week after the first slide, a much smaller slide came down, leading crews to pause their efforts for the winter.

They cleared the remaining debris in the spring, but the mark of the slide was prominent for decades — a wide gash in the hillside where one cabin, which had been narrowly missed by the mud flow, stood alone.

“That cabin was still there, I want to say, into the 50s, maybe into the 60s,” Shaw said. “And for years, there was no basic development. There were areas along Franklin, South Franklin, where there were no buildings.”

Today, the street is fully redeveloped. The area where the Cold Storage Building stood is a vacant lot, but the stretch of South Franklin Street opposite that lot is the heart of Juneau’s tourist district. On any given summer day, hundreds or thousands of cruise ship visitors wander in and out of gift shops that line the street. Some of those gift shops have apartments upstairs.

‘Juneau is built against a hill’

“Juneau is built against a hill, not just a rolling land but a gigantic mountain of hard rock covered in shale and loose dirt,” wrote Juneau resident George L. Webb, in a December 1936 letter to his family. “The rainfall last month was over 25 inches, which is a great deal for any century.”

According to Sonia Nagorski, a professor of geology at the University of Alaska Southeast, Webb’s letter describes the basic ingredients that trigger a landslide — a heavy bout of rain on a steep slope covered in loose sediment.

“In Juneau, we’ve built up, you know, numerous houses right along the edge of these slopes,” Nagorski said.

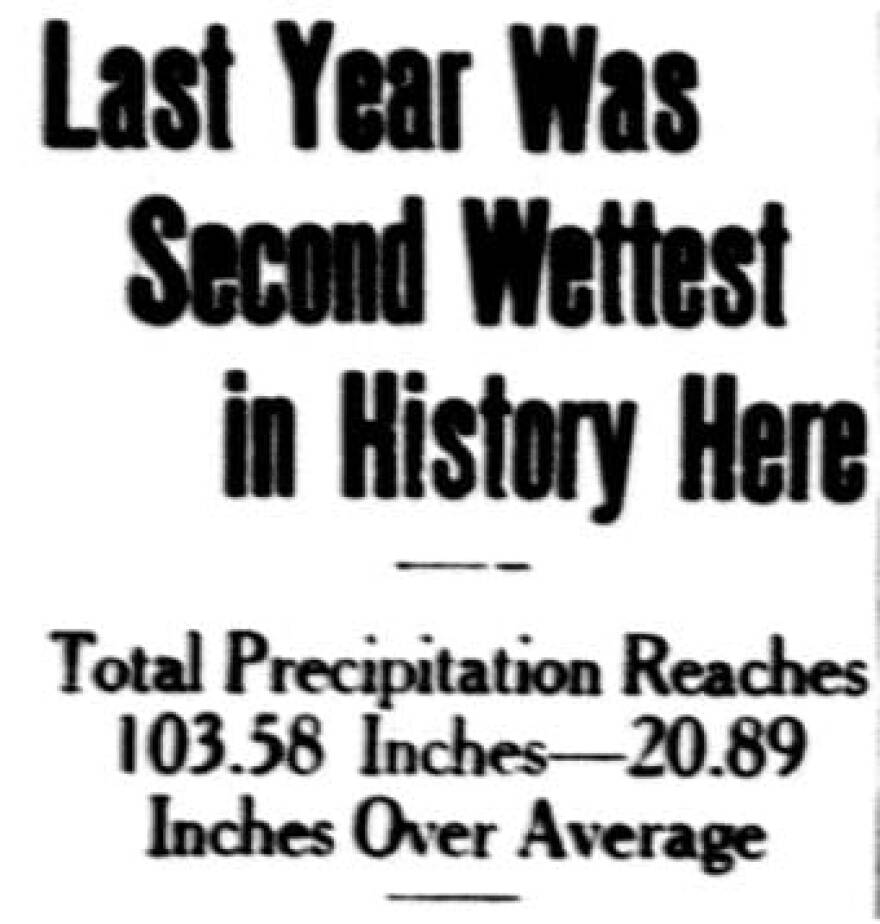

In 1936, the stretch of South Franklin Street at the base of Mount Roberts was one of Juneau’s most densely populated neighborhoods. A remarkable amount of rain saturated the mountain slopes that November. More than two feet — 25.87 inches — fell in the course of the month.

“First one record is broken, then another, until finally all the records are broken,” the Daily Alaska Empire reported a week after the landslide. “Now the meteorologist has put away his record book.”

Southeast Alaska’s geology is well-suited for heavy rains. Most of the time, the soils can drain the water fast. But if the drenching passes a certain point, water pressure starts to build up under the soil, and the solid earth is transformed into a viscous slurry of soil and water.

That can trigger a debris flow — the most common kind of destructive landslide in Southeast Alaska — where viscous earth mixes with boulders, trees and other debris as it flows rapidly down a slope.

Nearly four inches of rain fell in the 24 hours leading up to the 1936 slide.

“It’s those heavy rain events — on top of conditions that were already rainy for a while — that seem to be the most hazardous,” Nagorski said.

In Wrangell, the storm that led up to the fatal Nov. 20 landslide dumped three inches of rain in 24 hours. More than one inch fell in just six hours before the slide.

And human-caused climate change is making heavy rain more common. Most of the heaviest, most prolonged rainfall in Southeast Alaska comes in tropical fronts known as atmospheric rivers, which are becoming more frequent.

Other deadly landslides in recent memory — the 2015 Kramer slide in Sitkaand the 2020 Beach Road slide in Haines — happened during record rainfall events brought on by atmospheric rivers.

So as the region gets wetter, landslides may become more common, too. But they have always happened in Southeast Alaska, and in Juneau.

In 1920, a debris flow came down on Gastineau Avenue, destroying 16 buildings including a boarding house, three homes and a dozen small cabins. It killed four people.

Another Gastineau Avenue slide destroyed a house in 1929.

And just weeks before the Nov. 22, 1936 slide, a debris flow came down Mount Roberts and across Gastineau Avenue, breaking through the back of the Alaska Hotel, damaging two houses and burying one woman, who ultimately survived.

A series of slides downtown

Some blamed those slides on the AJ Mine, which cleared trees and operated its mill on the slopes of Mount Roberts.

In 1920, the AJ Flume overflowed just before the deadly slide. But that overflow came on top of snowmelt and nearly 2 inches of heavy rain over 24 hours. Geologists would later say that overflow from the mine did not cause the slide by itself.

Gust Erickson and two other men who lost their wives and homes in the November 1936 slide filed lawsuits against AJ Mine, claiming that the company neglected to maintain the hillside. A deep crack in the ground beneath the flume was noted around the time of the slide. That may have contributed, but geologists would later determine that the slide began much further up the ridge.

And even after the mine closed in 1944, slides off Mount Roberts kept happening. In October 1952, three more slides came down across Gastineau Avenue and South Franklin Street after a rapid burst of heavy rain. They destroyed two houses, and they came down within — or extremely close to — the same paths as the 1920 and 1936 slides.

Albert Shaw said he’s tracked landslides and avalanches in Juneau closely throughout his life, ever since he first saw the carnage on South Franklin Street in 1936.

“Stuff has come off the hillside repeatedly. Now, it’s apparently slowed down. But that gives you a false sense of security,” Shaw said.

Though Juneau hasn’t had a fatal slide since 1936, Shaw feels that’s just luck. He’s spoken outat city meetings on hazard mapping in recent months, urging the city to enforce stronger precautions for development in slide zones.

Just last month, the Juneau Assembly voted to repeal hazard maps and development restrictions in landslide zones.

Nagorski, the geologist, said we can’t know when the next disastrous slide will happen.

“They don’t necessarily follow some regular temporal pattern, like a regular interval,” Nagorwski said. “It’s possible that a slope might not fail for the next several hundred years, or it might fail in the next atmospheric river.”

But the most likely locations for a major slide, she added, are known.

When a landslide happens, it changes the slope, the vegetation and the way water flows down a hillside. That can make the slope susceptible to more landslides. And when a slide comes down, the debris flow can exploit natural gullies that funnel it down the hill. Or it can tap into channels that were carved by slides that came before it.

“So the places around downtown — or anywhere in Juneau — that you would expect debris flow would be where they’ve happened before,” Nagorski said.

‘And the little spark of life went out’

For the men searching the rubble in 1936, the sound of Lorraine’s pleading voice felt too good to be true after nearly 48 hours of digging in the rain and mainly finding crushed bodies. Dozens of shocked and frantic rescue workers set to work digging her out.

“Faster, faster, flew the shovels,” wrote the Empire. “Hardened, calloused men who have often flirted with death were whipped into frenzied heights of energy as they heard that plaintive little voice call out ‘mother.’”

By this time, the body of Lorraine’s mother, Delia Vaneli, had already been recovered. Her father Joe would be found dead a few days later.

It took rescue crews more than three hours to reach the toddler. She was huddled about 10 feet down in a small air pocket in the wreckage of the Nickovich apartment building — just a few hundred yards from where the downtown Juneau library stands today.

Lorraine was alive and responsive, but she’d been pinned face down for almost two days, and she was badly bruised. A wooden chest had fallen on top of her. Her left hand was crushed, stuck beneath a fallen beam. Her legs were blistered and burned from the underground fires.

She wore a jacket and a pair of ski pants that kept her warm from the November chill, and underneath, a pink silk dress and a string of gold beads she’d been dressed in for the dinner party. As Mattielli carried her out, Lorraine pushed her mop of curly brown hair away from her face, revealing wide brown eyes. She didn’t cry, the paper reported.

She was rushed to nearby St. Ann’s Hospital, where doctors tried to warm her up and tend to her wounds. But she died less than two hours later.

“The exposure and shock of being under the slide was more than was possible for the three-year-old to endure,” the Empire wrote. “And the little spark of life went out.”

The following Juneau residents died in the 1936 landslide

- Forrest Beaudin, 14 years. A student at Juneau High school and the son of Lucia Hoag.

- Pete Battello, 54. Owner of the North Transfer Company.

- Cora Erickson, 64.

- James Hoag, 40.

- Lucia Hoag, 42.

- Callie Lee, 38.

- Lena Peterson, 48. A seamstress at Snow White Laundry in Juneau.

- Hilja Peterson, 47. Store owner.

- Hugo Peterson, 46. Store owner and member of the Coast Guard Tallapoosa crew.

- Pauline Lott (Latt), 55. A dressmaker.

- Oscar Laito, 65. From Sitka.

- Marie Mattson, 58. Proprietor of the Mattson Boarding House and wife of jeweler Fred Mattson.

- Delia Vaneli (Giovanele), age unknown.

- Lorraine Vaneli (Giovanele), 3.

- Joe Vaneli (Giovanele), 30. Electrician and maintenance man at the Gastineau Hotel.