Beavers are moving into the Arctic. Scientists at the University of Alaska Fairbanks are seeing thousands of new beaver ponds changing streams and rivers, and accelerating climate change. The effects are so dramatic they can be seen from space.

Climate change is allowing taller shrubs to move into the Arctic and beavers are following, according to UAF ecologist Dr. Ken Tape.

“It's shocking, the places that they are,” Tape said. “You go out to these windswept, tundra areas, and you just think, ‘Really?’”

Tape said he and colleagues have found beaver lodges on those unlikely treeless plains, with a few shrubs. But overall, the Alaskan Arctic is becoming a friendlier place for beavers.

“There’s more shrubby vegetation. Winters are shorter, and there's more unfrozen water in these streams, so we know that their habitat's improving,” he said.

Tape said American beavers are now rebounding from overtrapping in the past. But he has no evidence that they have lived in the Arctic before.

“It's hard for us to tell how much of this is them just reclaiming some former range, and how much of this is climate change encouraging them into these new areas,” Tape said.

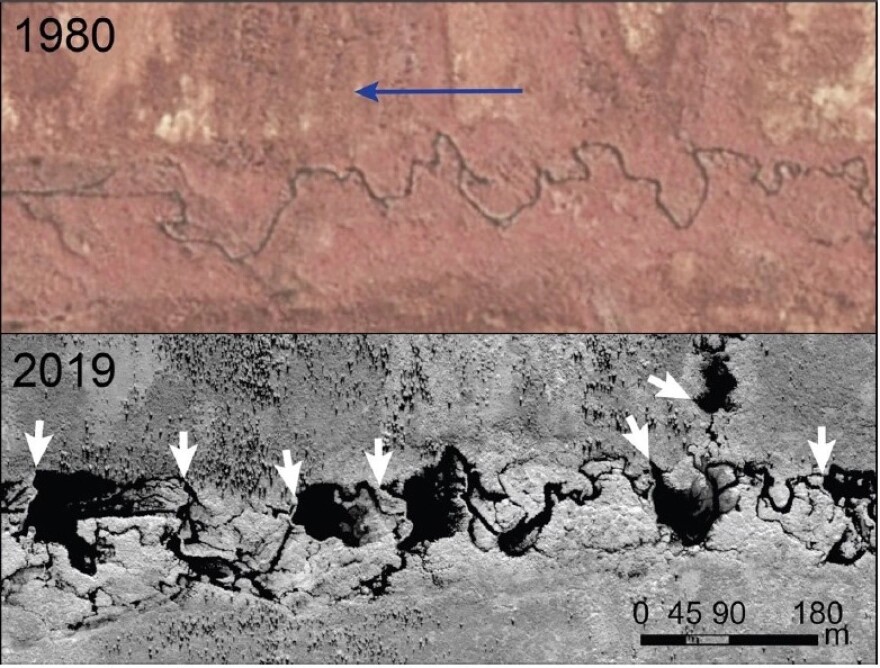

Tape and his colleagues, Jason A. Clark, Benjamin M. Jones and Benjamin V. Gaglioti from UAF and Seth Kantner from Kotzebue, published a paper last spring about the beaver intrusion. They looked at aerial photos from the early 1950s and found no signs of beaver north of Alaska’s boreal forests. Then in 1980s satellite imagery, the first signs of widened streams and rivers began to appear.

In satellite imagery from 2003 to 2017, the beaver ponds doubled. What used to be a squiggly line of a creek now looks like a chain of beads, as ponds form behind dams. The group found 11,000 to 12,000 new beaver ponds across Northwest Alaska from Nome to Kotzebue. Where they didn’t see them was on the far North Slope, past the Brooks Range.

To Tape, the images are pretty convincing evidence that a warming Arctic is what is driving the beaver colonization.

“We've caught them in the act,” he said. “In all of Northern Alaska, there are zero beaver ponds. And the reason, when you sort of overlay topographic and climatic variables on those 12,000 locations, is that temperature is a big constraint. It is THE big constraint that is preventing them from going on the North Slope.”

The data also show that the beavers are accelerating the warming.

“When you put a pond on a stream or on preexisting tundra vegetation, it absorbs heat more readily,” Tape said. “That warmer water is gonna thaw permafrost, which we see happening.”

There is a lot more open water, more melting permafrost and more groundwater flow now across the Seward Peninsula.

And whether this is good or bad depends on how adaptable you are. A warming Arctic will benefit some species.

“At the end of winter, that's your coldest moment of the year,” Tape said. “At the end of winter, you still have liquid water at the bottom of these ponds, and so it's almost like having a groundwater spring -- you're gonna have species in that stream that suddenly can survive year-round.”

Beaver colonization of the tundra represents a disturbance as great as wildfire, the scientists say. There’s no other animal that has changed the Arctic so much, so fast, except for humans.