A lot of science involves happy accidents.

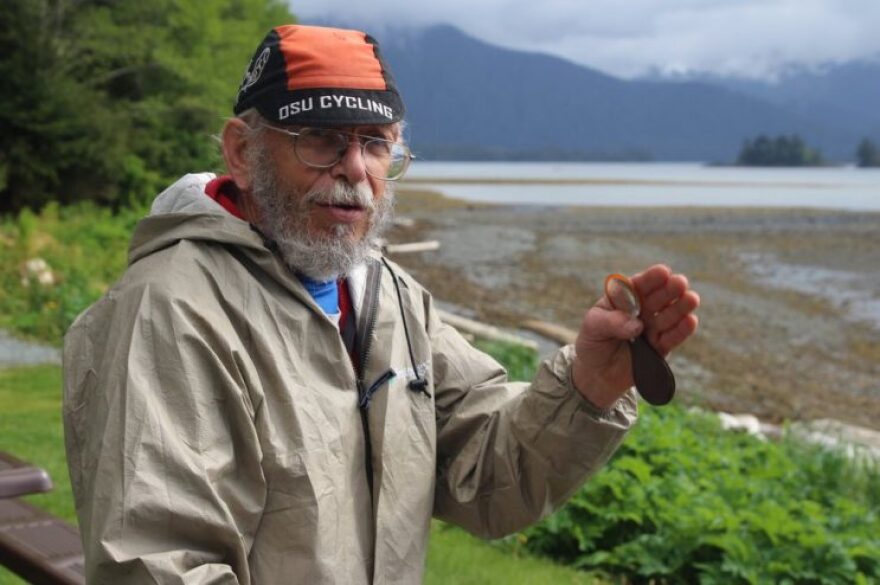

Late last month a retired scientist from Oregon stepped off the ferry in Sitka, and on a hunch decided to look around the woods for an old friend.

And while his discovery sheds light on one of the more obscure corners of entomology, it also is a clue to how humans may have survived the Ice Age in North America.

Forty years ago, Loren Russell discovered a kind of flightless flea while doing graduate research at Oregon State University.

Actually, Russell can’t claim full discovery rights. There was this undergrad, but what do they know?

"I’m the second person to actually look at it in its space, because I was showing the sample to an undergraduate who wandered through, and I said, 'Hey, look at this one! I thought it was something entirely different,'" Russell said. "And he said, 'No, it doesn’t have that.' I looked at it. Oh, well. Most people at that point say meh and go on. But I kept it."

So it’s pretty great to find a new anything on the planet, but it’s not like discovering penicillin, or a cure for cancer.

Russell knew there wouldn’t be much buzz around this insect.

"There’s a genus Caurinus. They are related to something that’s sometimes called scorpion flies," Russell said. "But they are so obscure you just have to be into Caurinus to enjoy them. They’re tiny little guys, about the size of fleas. They hop like fleas, and some of them probably evolved into fleas. In Oregon, we call it The Oregon Funnybug."

After earning his Ph.D., Russell became a scientist for the Environmental Protection Agency, and — as many a grad student has done — left his thesis and the funnybug behind him. He believed that the funnybug only inhabited the so-called “fog belt” from the middle coast range in Oregon to the Olympic Peninsula.

But then on a vacation to Alaska in May 2017, Russell takes a stroll through Sitka National Historical Park and easily finds a funnybug. And by doing so, Russell has just joined the ongoing academic debate over how humans migrated to North America.

The funnybug contributes to the mounting evidence that along the coast during the Ice Age, there were many places that had no ice.

The funnybug doesn’t fly. It doesn’t move around much. It’s a vegetarian. It’s presence in Sitka is a big question mark.

“Some of these insects had to survive in place," Russell said. "Something with wings, something that rides on other organisms, could recolonize this region. But a little forest critter without wings almost had to have a place to ride it out.”

But it’s not just Sitka. Caurinus dectes has also been identified in Vancouver, and on Prince of Wales Island. Russell lent his expertise to that survey about 5 years ago.

Actually, it’s not a pure lucky stroke that Russell found the funnybug in Sitka. He was acting on a solid hunch.

"You have to look," Russell said. "The odd thing is that this is an insect that’s relatively common. It’s hiding in plain sight. Entomologists don’t typically have the luxury to go out and survey something for some reason. And most entomologists don’t do much in the winter, which is the primary period when these are active farther south. Here, you have to go in the rainforest and — in my case — you have to look at the host plants, the liverworts growing on tree trunks. If I look, I can usually find them."

Russell was also planning to look in Ketchikan on his return trip home. He’s contributing his samples to researchers back at OSU, who are using DNA analysis — a technique undiscovered when Russell first found the funnybug — to identify what might be discreet species of the insect.

What’s next for Russell? Looking even farther afield for the funnybug, of course.

“I think this genus, or something similar could very easily be on the Asian side of the Pacific,” Russell said.