A tribal citizen science network that got its start in Alaska is being touted as a model for tracking climate change in the Arctic. The eight-nation Arctic Council plans to expand the Local Environmental Observer Network to other Arctic nations.

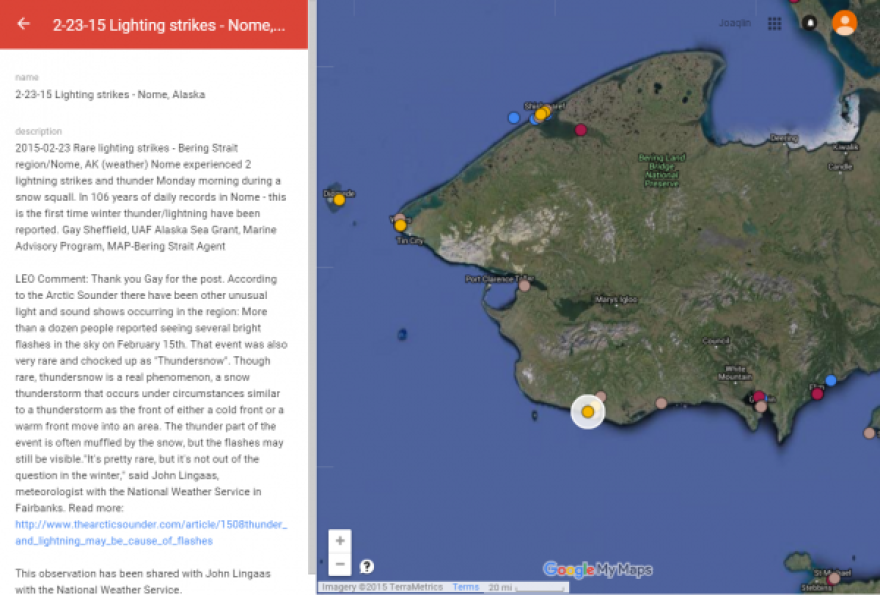

Alaska's 120 or so Local Environmental Observers document the rare, unusual or unprecedented. a brown bear foraging for food in January in Port Heiden, lightning during a snowstorm in Nome, erosion, flooding, droughts, invasive plants and animal die-offs - anything that could affect food or water security or community health.

At the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, Mike Brubaker is director of the Center for Climate and Health, which created LEO. He said most of the LEO observers are tribal environmental experts who have lived 10, 20 or more years in their community, and have knowledge handed down through the generations. He said LEO also has experts who can share other perspectives and sometimes answer questions - what caused an animal die-off, or whether a species is far outside its normal range.

"There's also people that are topic experts both locally, and around the state, at universities, or at agencies, or at different organizations," said Brubaker."And we depend heavily on those members of the LEO network, who are maybe not on the observation side but they're in sort of the ground-truthing and providing technical assistance side."

If you go to the LEO website, you'll see an interactive map created by Geographer Moses Tcheripanoff. He said there are several ways to access information.

"In the dialogue box it has the observation, the title of the observation, as well as the community where the observations occurred, the date, as well as the category," said Tcheripanoff.

Program assistant Mary Mullan also posts data, and works with the observers, who are not paid by the LEO network - most add the observations to their other duties working for a tribe. She said their motivation is to get the information out, and get answers.

"For these guys to get, to have a place to get questions and concerns out there with some sort of consult coming back is very positive," said Mullan. "Because eventually with these things, they're going to have to learn, if things continue to change, they're going to have to figure out ways to change their lifestyles to still live there."

Local Environmental Observer Wilson Justin agrees the LEO network will help people adapt to the changes associated with climate change.

"Number one you want to understand the speed of change," said Justin. "If you never observe anything, change always amazes you when it happens. It falls on you like a truck hits you. But if you're constantly observing and making notes you begin to accommodate speed and you begin to think about not only are the changes happening on a calendar basis, but then the next thought is if this keeps up we're going to have change in a very short period of time, what do I have to do to adapt to those changes and the potential impact."

In addition to the observers in Alaska, LEO has a few in Canada. The Arctic Council, which is made up of representatives of circumpolar nations, has adopted a recommendation to create a Circumpolar Local Environmental Organization, using LEO as a model.