The tiny but mighty phytoplankton live at the base of the food chain in the Gulf of Alaska. They're a food source for small crustaceans, which in turn feed small fish, then bigger fish, then seabirds and marine mammals.

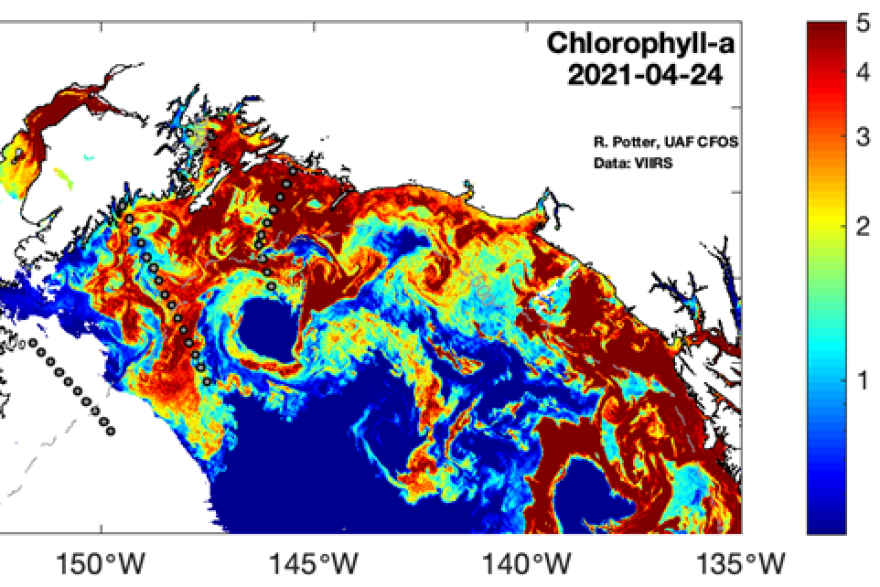

Each spring and summer, a large concentration of phytoplankton blooms in the gulf. This year, researchers recorded the biggest bloom they’ve ever seen.

“Which theoretically means we should have a very productive year at a whole bunch of other steps in the food chain," said Russ Hopcroft, a professor with the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

He said the phytoplankton bloom in itself is nothing out of the ordinary.

“Part of the natural cycle in the Gulf of Alaska is that when the light starts coming back in the spring and the storms start to subside a little bit, we get a big explosion of life in the phytoplankton," he said.

RELATED: With low stocks and closures looming, Bering Sea crab fleet braces for another blow

Hopcroft said people on passing ships might not register the large amounts of phytoplankton, besides more activity from birds or fish in the area.

But researchers keeping tabs on the blooms have noticed. They monitor the area each May, both with satellites and samples taken on a research vessel.

This year, the bloom spanned from Kayak Island near Cordova to Kodiak, dropping off where the gulf shelf plummets into deeper waters.

“I think we just had the right combination of some prolonged light and just enough storminess to keep things mixing a little bit, but not so much that they diluted and spread everything out," Hopcroft said.

Climate may also play a role. The Gulf of Alaska saw a heat wave between 2014 and 2017, nicknamed “the Blob,” which decimated some commercial fish populations and changed the marine makeup of the gulf.

“There wasn’t much of a bloom during the Blob," Hopcroft said.

But he said the gulf has seen more normal temperatures in this year, at times even trending slightly cold.

He said the hope is the energy from the phytoplankton make it up the food chain, from the fish that swim in the gulf’s waters all the way up to the Alaskans who eat them.