Review of Ruth Gruber, Photojournalist at the Anchorage Museum (Nov 2, 2012 —Jan 6, 2013)

For baby-boomers who went to elementary school in the fifties, World War II was too raw for school curricula. Most of my friends had fathers who experienced battle. Defining PTSD was decades away, so they coped by drinking quarts of alcohol to ease pain. The Holocaust was never mentioned at Chestnut Hill, my elementary school. I would hear adults speak about the movie, The Diary of Anne Frank. I didn’t read Anne Frank until Miss Baker’s English class, seventh grade at Beaver Country Day.

Fast forward to photojournalist Ruth Gruber–Anchorage Museum’s fall exhibition of flatwork, a looped video, and some correspondence. Sadly, the museum placed this important documentation in an all-too-tiny gallery with minimal narrative explanation. Gruber, who now lives in an apartment overlooking Central Park, grew up in Brooklyn. In the early twentieth century when most women didn’t seek one college degree, she attended New York University, then the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and received a PhD from the University of Cologne; at that time she was the youngest in the world to obtain a doctorate degree. This show came from her reportage adventures in the Soviet Arctic, Alaska, and then in Europe and Asia after World War II. Some of Gruber’s images, people staring directly into her lens, seemed overly posed. Other works, where she caught subjects off-guard, delve into the human psyche and are haunting.

In the mid-thirties, Gruber began working for The New York Herald Tribune which took her to the Soviet Arctic. In her latest book Witness (Gruber has written many) she recalls her visit to Igarka, “Because there was no hotel, I was given a small room in the port administration building. It had a bed, a desk, a chair, a nail on the wall to hang clothes, and an electric light. Outside the kitchen door was the outhouse.” She took a commercial ship, the Anadyr, which was transporting people and lumber, along with a couple of polar bears, from Igarka to Vladivostok. With few available women, fights would often break out over females and one of the officers did profess his love for her. Gruber said she had free rein to photograph but felt conversations onboard were measured.

Photo A of this essay shows a deckhand who robotically resembles the machinery he is tending. A pulley at the top of the picture quite accidently looks like a laughing face and contrasts with the man’s stern persona. This image is not about a carnivalesque environment but about the dangers of ice and fog and working for an oppressive regime. In the thirties avant-garde art showed machinery spatially competing with robotic humans, often referencing war torn Europe and its dictatorships. It is hard to know everything Gruber saw in this deckhand and his work, but it’s clear this is not an idle snapshot taken on a luxury yacht but contains tropes of Modernism.

One her second trip to Siberia, Gruber had to wait three weeks in Moscow for her passport to be stamped. At six in the morning in pouring rain, she finally boarded a Junkers monoplane–no heat or lights in the cockpit. She flew over Alexandrovsky Central, a famed gulag, before landing in Yakutsk, a city of prefab wooden housing and native yurts of reindeer hide. Bathing was at the local bathhouse, Tuberculosis was rampant. Gruber interviewed the head of the secret police, who told her he rehabilitated prisoners with work and gave all exiles freedom. Skeptical, she waited until her guide, a probable spy, went out with friends. Gruber slipped a notebook in her bra, and headed to a bookstore run by a professor-Bolshevik political prisoner, who lived above the store with his wife and baby, to hear the truth.

In the early forties, The New York Herald Tribune contemplated sending Gruber to Alaska, anticipating its strategic importance in the anticipated World War. A pre-travel interview with Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, convinced him to hire her away from the paper. As a government representative, she danced at officer’s clubs, participated in a walrus hunt and hugged homesick soldiers who only wanted to hear her laugh. Gruber experienced several flying mishaps. She delayed boarding a plane to Nome which took off without her and crashed. A message from Ickes that needed decoding had saved her life. Another time a pilot flying without even a map made a forced landing on a beach near Point Barrow. She and the pilot shared a Hershey bar near the spot where Wiley Post and Will Rogers had perished. Ickes sent Gruber back to Alaska during the war to report on the Alcan Highway project, much to the objection of the presiding general who said, “We’ve got no bathroom facilities to take care of women.” Pulling rank, Ickes laughed, “You don’t know the plumbing this gal has lived with.”

In 1944, Ickes sent Gruber to Naples to rendezvous with the Henry Gibbons, a refugee ship heading for Oswego, New York. Gruber spent thirteen days crossing the Atlantic interviewing camp survivors and tells, “I can’t listen anymore, but I listened.” One man still wearing camp pajamas said, “We can’t tell you what they did to us. It was too obscene, and you are a young woman.” These refugees were detained until the end of the war when they were granted asylum by President Truman.

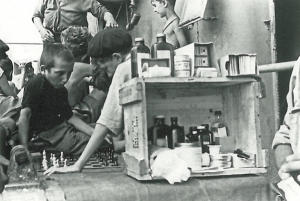

Photo B of this essay is about visualizing hope. Two boys in the foreground, clearly emaciated, survived unimaginable hardships. Now, they were crossing the ocean not knowing where they were going and for how long. It’s hard to believe that they could find enjoyment playing chess in the ship’s makeshift pharmacy.

In 1946, Gruber accompanied the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Palestine to Europe, attending the Nuremberg trials. Her brother Irving, a captain in George Patton’s medical unit, accompanied her. When watching Goering incessantly yawn, Gruber said, “I wish we were closer and I had a gun.” Next she traveled to Baghdad to interview a rabbi who helped her buy an aba (long robe) and yashmak (covering for the face) for a trip to Saudi Arabia. In spite of Gruber’s obtained visa and her willingness to sleep in the sultan’s harem, she was prevented from going by Sir John Singleton, “Don’t you know,” he shouted, “that no women are allowed to enter Saudi Arabia?”

Frustrated, Gruber soldiered on through the Middle East, interviewing Holocaust victims for The New York Post; as well as Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion who became a personal friend. She joked that with all his attention to opening up the Holy Land to all Jews, he took time to chide her for wearing a black dress and said, “Well, don’t wear black anymore, unless someone has died.”

In 1947, Gruber traveled with the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine for The New York Tribune. The British were slowly relinquishing control of the Holy Land, but they were still managing the hoards trying to enter. Gruber headed for Jerusalem and witnessed a rusty armada loaded with refugees docked in the neighboring port of Haifa, including the famed Exodus ship that had been attacked by the British for running a blockade. The idea was to encamp refugees in Cyprus, and allow 750 to enter Palestine each month. Gruber observed their living conditions, “The architecture had come straight out of Auschwitz.”

Photo C of this essay speaks aboutthe unsanitary and uncertain living conditions in the camp. Still, there was a baby boom as refugees wanted to rebuild their war-torn lives. In this photo, a father manages to assemble a bassinette out of rags and pieces of wood for his baby.

Next, Gruber headed for Port-de-Bouc, near Marseilles, where three refugee ships were desperately seeking asylum. She boarded the Runnymede Park and found half–naked people and reported, “the space they filled on that slimy floor was their kitchen, their dining room, their bedroom-everything.” In 1951, the New York Herald Tribune sent her to North Africa and the Middle East; it was also her honeymoon. Today at one hundred and one Ruth Gruber continues to focus on those oppressed.

Witness by Ruth Gruber (available on Amazon) complements her Anchorage Museum Exhibition. Although the book has emotional photography and riveting text, it was poorly edited and clumsily designed. I would have liked to learn more about Gruber’s experiences as a Jewish woman trying to succeed in an anti-Semitic and male chauvinistic era. The needed narrative that runs through the book gets chopped by pictures that feel thrown-in. Below these photographs are details that should have been assimilated into the text and not left as photographic taglines. It’s as if a mosaic crashed onto the floor and someone must crawl around and reassemble all the pieces. However, reassembling to read Witness is very much worth it because Gruber’s eyewitness photography and explanations should be contemplated. Sadly, most of us baby-boomers’ only recollections came from listening to Andy Williams sing the theme song from the movie Exodus.