Pablo and the fish and I are headed in the general direction of home, which lies to the southwest. In order to get there from here, we first have to travel more than a hundred miles northwest. That’s just the way things are in Alaska, what with its paucity of highways.

Now I find myself thirty-three miles farther away and in the little town of Chitina. We’ve been away from home for nine days, eventually making our way to the seaport town of Valdez in Prince William Sound. That’s where we acquired the fish.

Pablo is an orange-eyed parrot. To be exact, he’s a Mexican Double Yellow-Headed Green Amazon, and he likes to travel with me in my truck and camping trailer. The fish are not pets. They’re dinner. Fresh troll-caught silver salmon from the waters of Valdez Arm, courtesy of Bill and Betty and an afternoon spent on their boat. Betty counted the fish as “two and a half” as one is particularly small, and contained neither eggs nor milt.

Somewhere along the way that little salmon began swimming with the wrong crowd, maybe took an unplanned turn in the ocean when bigger fish swam past. Now, instead of another year in the ocean to grow and produce roe or milt, it’s in my refrigerator. I was thinking about that fish this afternoon, after we left Valdez, serpentined our way through narrow Keystone Canyon with its Horsetail and Bridal Veil Falls, climbed over twenty-six hundred feet to the summit of Thompson Pass, and hiked around Worthington Glacier.

How did that little salmon come to be swimming with a school of much older, much larger fish?

Anyway, about one o’clock this afternoon, as we were approaching what I felt was nap time, my foot eased the brake on and my hands turned the steering wheel to the right and suddenly, without forethought, we were headed for Chitina on the Edgerton Highway, the opposite direction from home.

Chitina is an historic little town in its own right, but then, most of Alaska is historic in one way or another. Chitina was established in 1908 as the northern terminus of the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad (CR&NW), cynically, and perhaps affectionately, referred to as the Can’t Run and Never Will Railroad. This town also served as a mining supply town for the Kennecott Copper mine, more than sixty miles away at Kennicott. I didn’t make a typo there—those are the correct spellings, all the result of a lack of proof-reading many, many years ago.

Today, Chitina is known for three things: Copper River salmon dip-netting, the start of the road to McCarthy, and a well-known bumper sticker that reads: “Where the he– is Chitina?”

So here we are, Pablo and me, and the fish, camped beside the great Copper River, just downstream of about a dozen fish wheels that are churning in the turbid waters, the big baskets occasionally scooping up a salmon. Like that little fish now in my refrigerator, I made an unintended turn, but that turn has brought back a flood of memories about old friends, far away destinations, and the worst and best dog team I ever had.

***

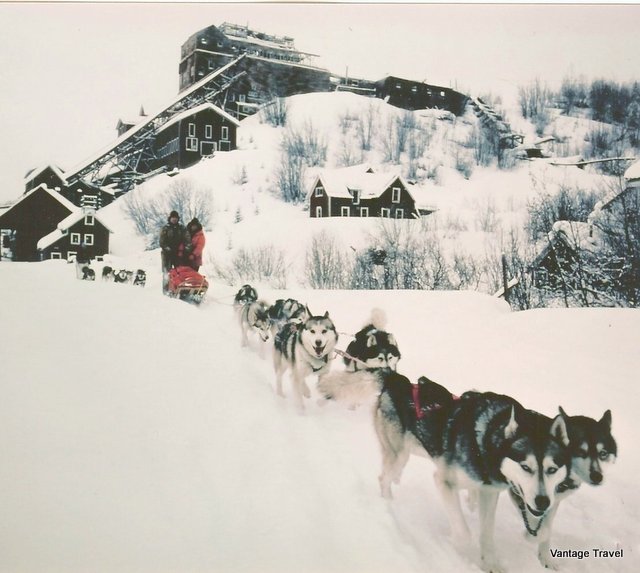

Thirty-some years ago my friend Ramona had the use of her friend’s team of Malemute-McKenzie River huskies. These were working dogs, used by her friend Steve to haul freight and gear on Mt. McKinley for mountain climbing teams. During his off-season, Ramona ran them to keep them in shape.

Down the road lived my team of pets, Siberian huskies mostly, though one of them was rumored to be one-eighth wolf. He sired a litter by one of my females, and I kept two of the pups. They were now my lead dogs Mugsy and Bashful. I used my team for recreation and a ten-mile run was a good workout for us.

Ramona and I decided to take on a bigger challenge one winter—we wanted to mush to the old copper mining town of McCarthy, deep in the Wrangell-St. Elias area, where our friend Nancy owned a cabin. All the plans were made early in the winter, which gave me plenty of time to get my team of laggards into shape for the sixty-three mile run from Chitina to McCarthy on the rail bed of the defunct CR&NW.

I put in lots of time that winter getting those dogs ready. We got so a run of eighteen miles from our home to Cooper Landing and back wouldn’t make us collapse with exhaustion, and I was feeling somewhat optimistic about our chances of getting to McCarthy without totally disgracing ourselves in front of Ramona’s team of Mack trucks, as I called those huge, freight-pulling dogs.

As a tune-up trip, or shake-down cruise, we decided to run the dogs from the Petersville Road to Kroto Lake, where friends had a ski lodge. In the days preceding our run, the area received about four feet of new snow, making the trails slow and difficult. We were carrying heavy loads, trying to simulate as closely as possible the weight we would have to carry on the later trip.

It seemed to take hours to reach the lodge about ten or twelve miles off the road, and I was feeling discouraged about our chances on the Chitina-McCarthy trip, but kept my concerns to myself. I was a bit more optimistic the morning we prepared to leave the lodge and head back to the trucks, and hoped my dogs would perform better.

Once on the trail they seemed even slower, and I was mentally writing the script I would have to repeat to Ramona and Nancy as I cancelled my participation in the upcoming journey. To make things worse, I’d neglected to bring booties for the dogs and the new snow was clinging to some of the dogs’ feet, forming huge, painful snowballs. Every few minutes I would have to stop the team and pull chunks of snow from the huskies’ feet.

As we approached a large open area, a red and white Super Cub on skis landed in the soft snow. When it came to a stop the small airplane sank to the fuselage, supported only by the “tail feathers.” It was my husband Ken, who was supposed to have flown in to the lodge at Kroto Creek but the weather had not permitted. Now, here he was, buried in deep snow alongside the trail back to the Petersville Road.

Wearing hip boots, he waded through the soft snow over to the packed trail where I waited with my dogs. After some initial conversation, I told him how disappointed I was in my team’s performance and how I was thinking of canceling the long awaited trip to McCarthy.

I asked him how much farther we had to go to get to the Petersville Road, telling him we’d already been on the trail an hour.

“Why, you’re there,” he said. “It’s just beyond this clearing.”

Whoa! Ten miles in an hour with stopping every few minutes to remove snowballs. Maybe I should reconsider my pessimistic attitude, I thought, as I watched him get the small plane up on step and fly away.

***

And so it was that in late March the two of us, plus Nancy, camped in a freezing cold cabin in Chitina the night before our departure to McCarthy. We were doing our best to keep the dogs quiet and not disturb any neighbors, so I put my two lead dogs in the back of my truck for the night.

The next morning I discovered that Mugsy and Bashful had raided the supplies for the trip and had eaten most of five pounds of fat chunks that were meant to be dog snacks for the entire week-long trip. I had two very hung-over huskies on my hands. They would much rather have spent the day retching and sleeping than harnessed and running, but their reprieve lasted only eleven miles down the McCarthy road before we came to a place to park where there was enough snow on the road to run dogs. It was our bad luck that the road had been plowed recently in preparation for the spring mining mobilization.

Once in harness, Mugsy and Bashful let me know often just how sick they were, pausing to disgorge chunks of fat, and in general running about as slowly as tortoises. At one point Mugsy gave up and refused to go any farther. I unsnapped him from his position in lead and put him father back in the team, a huge insult to a lead dog. He trotted dejectedly for a while and when I put him back in lead after a few miles, he kept his traces taut but we still traveled slowly.

Ramona and Nancy with the team of Mack trucks didn’t travel too fast either, but were ahead of us by a good distance most of the time. They would stop and wait for us to catch up, occasionally letting us go on ahead and then running past us.

After thirty-three miles we arrived at the home of friends, where we camped in an old cabin for the night. The temperature was slightly below zero the next morning when we set out. Our friend, who once had worked for Susan Butcher, the famed Iditarod musher, offered to run her own team ahead and show us a better trail down the lake that eventually came back to the road. Away she went, and when she finally stopped and waited for us to catch up I could read the look on her face: “You call those dog teams?”

Mugsy seemed to feel better that day and we mushed into McCarthy in mid-afternoon. We found places to stake the dogs close to Nancy’s cabin, but far enough away to not bother any residents of the town. We built a fire in the woodstove in the cabin, fed the teams, fed ourselves, and settled in by lantern light for the evening.

About a half hour later there was a knock at the door. It was my husband Ken, who’d flown in to join us. The next day we hooked up the dog teams and mushed the five miles uphill to the Kennecott Mine ruins. Ken didn’t have much to say about my team’s performance and it’s just as well because most of what he did say wasn’t complimentary. He claimed he could walk in the deep snow faster than my team was moving. The trip down the road didn’t proceed much better and I had a pretty dismal outlook on dog mushing in general when we arrived at Nancy’s cabin.

The day Ken flew out was sunny and crisp and we had another side trip planned with the dogs. This time we were headed to the Nizina River, about eleven miles away, and an area of even more remote mining operations. I thought about bowing out, thinking I’d need to rest these useless dogs for a month before we could make it back to the trucks parked more than fifty miles away.

The trip to the Nizina was a little better, with my dogs trotting along. We climbed the switchback trail out of the glacial valley where McCarthy lay, then along a mountain flank until we began a steep descent towards the Nizina River. Sometimes we led, sometimes we followed. We arrived at the Nizina in early afternoon, and spent a sun-drenched hour eating lunch and basking in the warmth. It was almost break-up on the river, with open channels cutting away at what had been solid trails across the river ice. All too soon it was time to head back, if we wanted to reach town before dark.

I suggested to Nancy and Ramona that they go on ahead and maybe my dogs would move a little faster if they knew another team was ahead of them. We had a mile long, steep climb out of the riverbed, and I wasn’t looking forward to it. Ramona roused her team and took off. Nancy started up the hill on foot. My dogs complained loudly, but I held them back for about fifteen minutes before I let them go. When I did, they shot out of there, whip-lashing my neck with their sudden start.

A quarter of the way up the long climb I spotted Nancy and yelled at her to jump on the sled as I went by. I could barely slow the dogs as Nancy grabbed the handlebar and swung onto one runner. The dogs never noticed the extra weight.

They’ll slow down after we reach Ramona’s team, I thought, and then it’ll be five miles an hour or less back to town.

Not a chance. We passed Ramona’s team in a blur and shot up the hill. There was no way these dogs were going to slow down. Ramona’s team gave it everything, but those huge heavy dogs were no match for these Siberians that were less than half their weight. We crested the hill and raced down the trail, quickly losing sight of Ramona and her team. Several miles down the road I stopped the dogs and made them wait for Ramona to catch up. Nancy and I gawked at each other in complete disbelief.

The dogs barked and yipped, lunging at their traces, anxious to go. I tried making them run behind Ramona’s team, tried riding the brake. Nothing would slow them. They were on a mission and they were going to get there as quickly as possible.

I was impressed. This is a fine team, I marveled. Wonder what they’ll do tomorrow on the way out of McCarthy?

***

Less than an hour and a half after leaving McCarthy we were twenty miles down the road at our friends’ house, who once again were expecting us to stay. We opted to push on as it was only noon, and the dogs were complaining loudly about having to stop even for a few minutes.

We zoomed out of our friends’ yard and flew up the road. The weather had not been kind to the road. The warmth and sun had melted even more snow and large patches of gravel faced us, especially on the south-facing hills. My dogs didn’t even slow, sprinting up hills, racing each other on the flats.

It was as if they were running free, unfettered, the wind in their faces. They moved with the grace of finely conditioned athletes, their muscles and tendons and ligaments stretching and contracting, rippling their glistening black and silver and white coats. Their eyes—blue or brown or, in Wolf’s case, a luminous unfathomable amber—sparkled with joy. There were huge grins on their faces and their pink tongues flapped from the sides of their mouths.

I can still see them loping up the road, forging ahead with little effort as if the heavily loaded sled wasn’t even attached to their harnesses and gang line. They ran as freely as their lupine forebears.

I pulled them to a stop once each hour, forcing a five to ten minute rest break on them. They responded by leaping crazily into the air, yipping and begging to run. They had no use for rest breaks, but I felt it only polite to give Ramona and her team a chance to catch up. Eventually, shaking her head in wonder, she told me to go on ahead—she would meet us at the trucks.

We flew up that road, splashing through melting snow, across glaciated patches, up bare gravels hills. Riding the brake did no good as they weren’t about to slow.

Soon I spotted the trucks and thought the dogs would pull up at ours as they usually did.

They did not. After more than fifty miles of running, they tore past it, with me yelling to Mugsy and Bashful to “gee”, or turn right, and “truck,” a word they knew. On past the truck we went about a quarter mile before I finally got some purchase with the sled brake and was able to turn them around and head back.

Only after I got them loaded into the truck did they settle down and accept the fact that their running was over for the day.

***

And that’s my story of how my coddled bunch of pets started running with the big dogs one day, how they disgraced themselves initially. And then, by some incredible fortune or strength of will, those seven Siberians excelled.

Here on the banks of the famed Copper River that whole journey has come back to me. Mugsy and Bashful and all the others are long gone now, all having lived well into their teens, but just for today they are alive in my heart and memory. I recall their faces, the color of their eyes, their personalities. I remember how much I loved them. I have to take a deep breath when I think of Mugsy and Bashful, how special they were and the mysterious connection we had. It seemed Mugsy could read my mind, and Bashful would read his and follow his lead.

I think of that little salmon in my refrigerator, caught before its time and destined for the dinner table. When that day comes, I’ll remember that fish that took an unplanned turn and swam with the big guys for a while—and brought a beloved dog team alive for me again, the finest dog team I was ever privileged to be part of.

Jeanne Waite Follett has lived in Alaska since 1948, graduating from Anchorage High School in 1960. As a reporter for the Anchorage Daily News after high school, she covered the Alaska Court System in its infancy after statehood, as well as federal and municipal courts. She also worked in radio, as a legal secretary, cook, electrician, and in construction. She and her husband puchased the renowned Jockey Club roadhouse in Moose Pass and reopened it as Trail Lake Ladge. They retired after selling it in 1996.

Jeanne is an award-winning writer and now blogs at http://gullible-gulliblestravels.blogspot.com.