I distinctly remember what I was wearing that late afternoon of March 27, 1964. It was a brand new, never worn before, robin’s egg blue cotton sheath. The kind with the tight pencil skirt half way down the calf, and only a short slit in the back. Typical of mid 1960 styles, it was slenderizing but did not allow much room for leg movement. Not that I needed any slenderizing.

At 22 years old, and standing 5’2”, I weighed not much over 100 lbs, even though it was only six months since David’s birth. But it was the day after my birthday, Friday, and my husband John and I had plans to have a “date” on the town that evening. As I carefully made up my face and hair, donned my prized blue straw 3” spike heels and started dinner, I thought about my new dress.

Mother had taken me to J. C. Penney’s the Sunday before and together we picked out my “birthday present”. And what a treat that blue dress was! On one income with two little ones to clothe and feed, there wasn’t anything left over for luxuries like new dresses.

John worked for Jerry Mulenos at Business Service Bureau, one of the first, if not THE first, computer company in Anchorage. My memory is that he worked on circuit boards. At BSB, bank after bank of these gargantuan circuit boards took up an entire room. They undoubtedly contained far less data than today’s smart phone does, sans the Internet. Output was processed on thousands of IBM punch cards.

I remember walking into the building on numerous occasions and hearing the whirr of the punch card machines. What an exciting new frontier, I thought at the time, never dreaming that computers would eventually take over virtually every aspect of our lives.

Jerry’s wife, Marianne, was prominent in the newly formed Greek Orthodox Church in Anchorage, sang in its choir and loved skating on the pond behind the Peanut Farm.

Looking back from the vantage point of 2012, the months that John worked at BSB had a sort of “Mad Men” flavor to them. I have vague memories of office parties where liquor flowed freely and the women were dressed to the “nines”. On our extremely slim budget, I very inexpertly sewed a floor length gown of emerald brocade satin that fit like a glove. I proudly wore it on at least one occasion before my pregnancies interfered.

But on this Good Friday, dressed, makeup on, and daydreaming set aside, I started pork chops cooking on the stove at about 5:00 p.m. John would not be home from work for another 45 minutes to an hour, and I wanted dinner to be ready when he came in the door.

We lived in a small trailer near the corner of Tudor Road and Old Seward Highway. Most likely the trailer was built in the mid 1930’s. It was single wide, perhaps 8’ x 35’, and had an attached lean-to that held a reasonable sized living area and master bedroom in the back. There was a small stand-up oil furnace inside somewhere near the entrance from the living room into the trailer. The cooking stove used propane that was piped in from a tank outside. What had once been the teeny living area in the trailer now served as a dining room where shelves were full of books and knickknacks.

For some reason, which I will never be able to explain in any terms other than supernatural, I moved the pork chops to an electric frying pan and turned off the propane burner. That one act, which had neither rhyme nor reason at the time, may have saved my life.

Lying on a blanket on the carpeting in front of the small black and white television, the kids were watching a cartoon. David, a sweet baby, was a stocky 18.5 lbs. at six months. Naomi, eighteen months old and 26 lbs., loved being his big sister. Typical for Alaskan homes, they were dressed in tee shirts, diapers and socks. Since the house was quite warm, there was no need for more clothing.

Outside it was about 25° and lightly snowing. At 5:30 there would still be light for a few hours. It was rush hour, if you could call it that, and a few people looking forward to Easter weekend were heading down the highway towards their homes on O’Malley, Huffman, De Armoun, or Rabbit Creek Roads. Our little trailer house, one of several set back from the highway, was perhaps 75′ behind a “fork and spoon” restaurant called Kitty’s Café. To the north of the café, on the corner of Tudor Road and Old Seward Highway, was North Star Fuel, a company run by my in-laws.

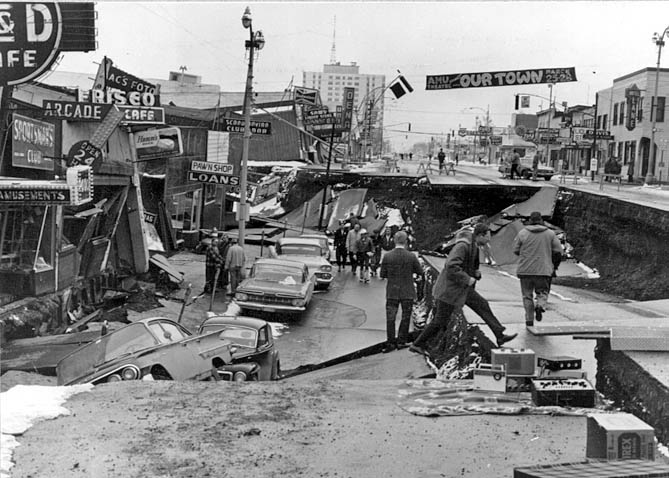

At 5:36 p.m. in Prince William Sound, 78 miles east of Anchorage, a fault between the Pacific and North American plates ruptured catastrophically, triggering a megathrust earthquake and calamitous tsunami.

The deafening roar came seconds before the shaking. Gathering speed, the sound became a runaway freight train, bearing down on anyone in its path. The world started to shake brutally, and as the expression goes, all hell broke loose.

Electricity was extinguished in that instant. Accompanying the roar of the earthquake was the sound of nearly everything falling and shattering around me. Immediately I picked up David under one arm, and led Naomi to the front door, opening it into the small, enclosed porch on the front of the lean-to where we stowed our boots and snow shovels.

Growing up in Anchorage, we had all been “schooled” in earthquake etiquette. “Stand in a doorway”, we had always been told, as the structure was presumed to provide stability and safety. Since eighty percent of our planet’s earthquake activity occurs in the Pacific seismic belt, Anchorage was no stranger to tremors.

It was immediately apparent, however, that this was no normal quake. All the ones of my youth, even the strong ones, had lasted briefly. A quick jolt or two and that was that, it was over. I remember standing in the hallway as a kid, having been awakened in the middle of the night by the house shaking. “Isn’t this fun”, my brother and I would say to each other as we rode it out for a few seconds.

Earthquakes were something to be joked about since nothing was ever damaged to any great extent. “Just another earthquake” we’d say. It was part of the fun of living on the frontier. These tremors also provided a topic of conversation at school the next day, giving us an opportunity to tease the “cheechakos” who generally had been completely unnerved.

This one appeared to have no inclination to end, however, and it became rapidly apparent that I needed to get my children to safety. The porch was swaying and creaking, threatening to break apart from the lean-to. The front porch door was swinging wildly in keeping with the sound of shattering coming from within.

I knew I had to take the children to Kitty’s Café, where there would be people to help. Gathering up Naomi, and clutching both children snugly to me, I made my way down the three or four icy steps of the porch to solid ground. And fell. All of us, sprawled on the ice-crusted snow on the driveway, kids half dressed, screaming, me – well, terrified didn’t even begin to describe it.

The trailer next door to us housed a dog that I avoided at all cost. He was a large mutt, a mixture of breeds whose one purpose was to intimidate and frighten anyone who approached. Frequently his keepers let him run loose, and I rarely ventured out until I first determined where he was. Now I could see him – a poor, wimpy excuse of a guard dog, running in circles with his tail between his legs, howling at the top of his lungs. It was obvious to me he was no threat.

As I lay there, I remember hearing the peculiar crackling and snapping sound that boots make when walking across crusted snow. But there was only the dog running in circles, and myself with two small screaming children sprawled on the icy ground. Later my in-laws told me they had been standing at a rear window in their fuel company, watching a fissure open and shut beneath the trailers, mere feet away from where we lay.

It was clear I had to somehow walk to the café. Cars had pulled over on the Old Seward Highway and men were standing on the pavement, holding on to their cars for dear life. “Why don’t they come help me?” I wondered, not understanding that they couldn’t move.

We didn’t lay there long. I’ll never know if I screamed it out loud or if it was only a thought in my mind, but I said, “Oh God, please help us!”

And instantly the most amazing peace came over me. The fear dissipated completely and very calmly, I stood up, lifting my two hefty little ones as I rose. And in my tight, robin’s egg blue cotton skirt, and 3” spiked heels, I walked, David clutched under one arm, and Naomi under the other, all the way to Kitty’s Café, and up the steps to safety inside.

By the time I reached the steps, the violent buckling of the earth had slowed and become more of a sea-swell motion.

Anchorage sits on an ancient glacial deposit known as Bootlegger Cove Clay. That deposit is comprised of “quick clay” that exists underground as a solid gel, but liquefies when shaken. In the Anchorage basin the result of the Good Friday earthquake was akin to shaking a bowl of jello. The ground shook and shuddered, and even after the major earth tremor subsided, the ground still trembled, for four minutes – a lifetime when you think you might die. Four minutes, perhaps five counting the jello effect. Longer than Elvis singing “Heartbreak Hotel” twice; longer than my routines in the Acrobatic Majorette Corp at Anchorage High School. Sometimes four minutes can be hours.

Inside, Kitty and her patrons were literally rattled, as was I. Naomi and David calmed down considerably and people offered up sweaters and shawls to wrap their chilly little bodies in. I sat down on a stool at the counter to gather my wits about me and stop shaking. The café telephone was not working and I knew that the phone in the trailer would not be, either.

By the time my nerves calmed sufficiently to think clearly, I realized that I should go back to the trailer for a quick look-see before it became so dark it would be impossible to access the damage. We also needed a few necessities: proper clothing for the children and myself, diapers, a bottle or two for David. That would tide us over for the meantime. And so, perhaps a half hour after the earth settled down, I borrowed a flashlight and gathering my courage about me, left the little ones with Kitty and walked back across the parking lot to what remained of my home.

The front door to the lean-to had slammed shut and locked, but I found the hidden key and going inside, discovered that the flame in the oil furnace had gone out and oil was flooding its belly. A quick fix: turn off the oil and deal with it later. Standing briefly in front of the propane range, I thought about the pork chops. If the burner had been left on, the house could easily have caught fire or blown up with me in it while I was looking for diapers and bottles and warm shoes.

The toilet tank was broken; lots of splintered glass and certainly a huge mess on the floor in every room, but nothing severe that I could see. I changed clothes and shoes, gathered up the few things that I had come for and with a sigh of relief, headed back across the parking lot to Kitty’s and the comfort of others.

We stayed at Kitty’s until John finally arrived. Traffic out of town was slow; people were freaked out and the roads were filled with debris and occasional fissures. His parents didn’t bother to check up on the children and me. As soon as the ground stopped shaking they left the fuel company to drive downtown and check on their house.

Some of the radio stations must have had generators, and started broadcasting again as the word had spread that people were missing or dead in Turnagain, a fairly new upscale subdivision on the bluffs overlooking Cook Inlet. Anchorage’s most prestigious subdivision was built on the 72’ tall bluffs, and 200 acres of land had slid down and forward toward the ocean. Ground collapsed 984 feet inland from the bluffs’ edge.

John, of course, was anxious to head back into town and join the search parties. I was terrified. I couldn’t stay at the café all night; and his suggestion that we return to our trailer was beyond unreasonable. I needed the security of other people. At 22, there were times I still needed my parents, and this was one of them. Finally, after I refused to stand down, John agreed that he would drive us to my parents and then go on to Turnagain, where he would join the search parties. Gathering up more supplies from the trailer, we headed back into Spenard and my parents’ house. Mother and Dad, needless to say, were relieved to see us.

Public communication was extremely limited and we had no idea how dire the situation was, not only in Anchorage, but in the rest of Southcentral Alaska. We would later learn that an Anchorage High School science teacher, Leora Knight, lost her life that afternoon in Turnagain. Her husband lost a leg, but survived. Eventually that summer I would make friends with Judy, a young mother whose daughter, born the same day as David, was tragically swept away during the tsunami that devastated Whittier following the earthquake. Judy was an inspiration to me as she dealt with the death of her daughter, along with recovering from her own serious injuries.

Fortunately there were not a large number of casualties from the quake itself, due mostly to solid wood construction and low population density. However, the ensuing tsunami also claimed lives, most in Alaska, but others in Oregon and California. Damage was severe and it took years to rebuild but as often happens during periods of crisis, people came together to help each other out. Folks opened their doors to strangers, offering food, clothing, and shelter.

A new sense of unity swept over our communities as we healed. Our world had been shaken to the core, but we emerged all the stronger.

Jana Ariane Nelson (nee Janet Griffith) moved to Anchorage in 1948 with her parents, Donald and Denney Griffith, and her twin brother, Jack.

Jana worked in the legal field in Anchorage before moving to Oregon. She retired from Lane Community College in Eugene where she was the Mathematics Division Coordinator.

Her daughter, Naomi Sweetman, is the Alaska DARE Coordinator and her son, John Nelson, is a financial advisor for Merrill Lynch in Anchorage. Jana has 4 grandchildren and one great grandchild in the Anchorage area. Her brother, Jack, runs the Griffith Lab at the University of North Carolina.

For more stories of early Anchorage, visit growingupanchorage.com.