For hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops and their families, when the Pentagon orders them to find health care off base there is none.

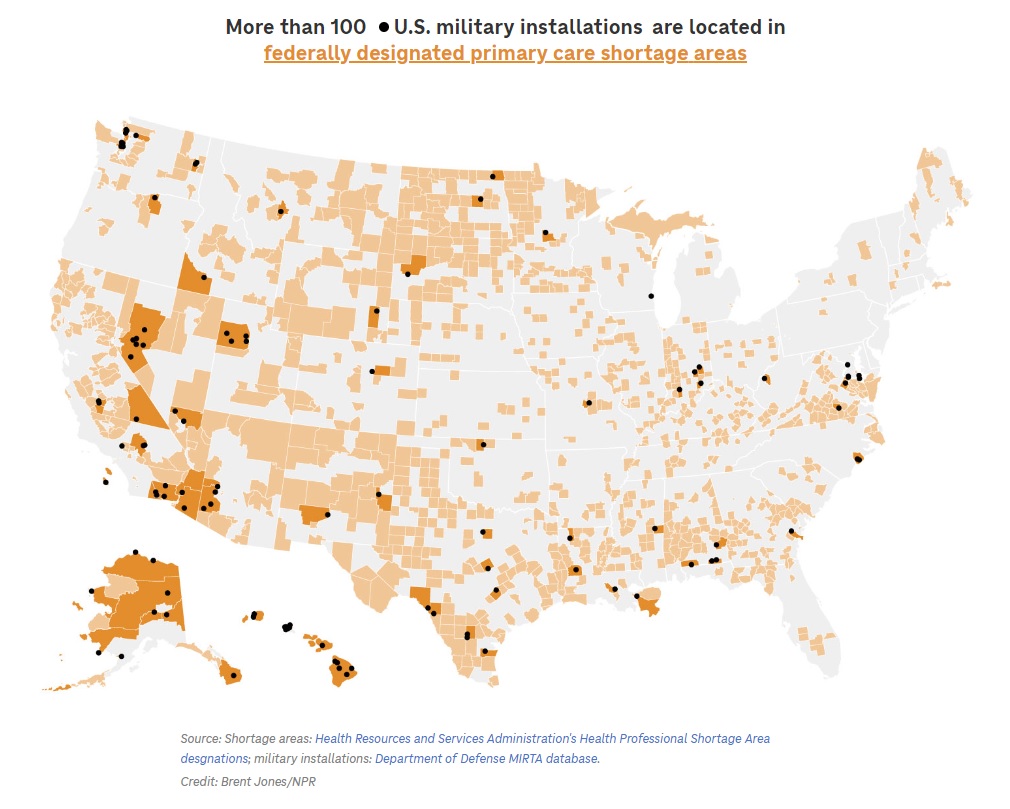

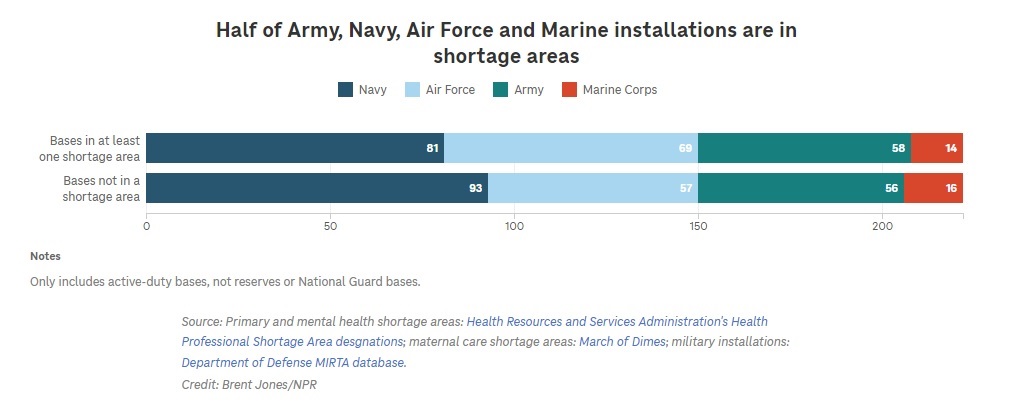

An NPR analysis found that 50% of active duty military installations stand within federally designated health professional shortage areas (HPSA). Those are places where medical services are hard to find — commonly called “health care deserts.”

“Military members often don’t have a lot of control over where they’re stationed. Certainly their families don’t,” says Eileen Huck, with the National Military Family Association.

“It’s incumbent on the military to make sure that when you send a family to a location, the support and resources are available to take care of them. And that obviously includes health care,” she says.

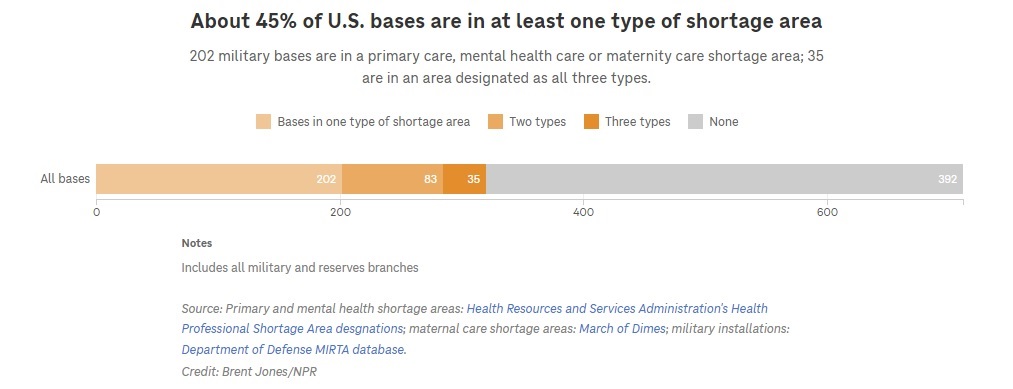

NPR mapped counties designated as shortage areas for primary care, mental health care and maternity care nationwide. Excluding National Guard installations, half the bases landed within at least one desert. Three out of four bases in primary care deserts are also in either a mental health care desert, a maternal care desert, or both. By population, 1 in 3 U.S. troops and their families live in a health care desert.

Three out of four bases in primary care deserts are also in a mental health care desert, a maternal care desert, or both.

For more than a decade, the Department of Defense has been trying to realign medical services, bringing the four branches of the military under one health agency with the aim of cutting costs and downsizing military treatment facilities. A big part was pushing family members away from treatment on base and out into the civilian community where they could use their Tricare health insurance. Troops, families and military retirees have used Tricare for decades, and it once enjoyed a good reputation. A joke about marrying a soldier used to go, “You had me at Tricare.”

Now the Pentagon admits the downsizing has gone too far and may be hurting military readiness, as well as recruitment, according to a DOD memo titled “Stabilizing and Improving the Military Health System.” Issues with access to care and medical staff shortages on base have been documented by a DOD Inspector General’s report.

“You do not have a robust surrounding civilian medical care,” says Sean Murphy, who served 44 years, retiring as deputy surgeon general of the Air Force. Civilians, he says, are free to choose where they live. Troops don’t get as much say about where they’re stationed.

“So you’re out with the rest of everybody in the boonies. And we have kind of promised the military members to have a certain level of care no matter where they are, ” he said.

Murphy says civilian health care is working on such low profit margins that many providers can’t afford to take Tricare’s low reimbursement rates — even in areas that are not health care deserts. When Murphy retired to North Carolina in 2021, he had trouble himself, getting turned down by four doctors before he found a fifth who would take Tricare.

“I’m the (former) deputy surgeon general of the Air Force!” he said with an ironic laugh.

Murphy is concerned that downsizing health care has hurt military readiness, leaving American troops less healthy and spiraling down the number of doctors, nurses and battlefield medics trained-up in the case of another war.

Military recruiting has lagged in recent years, and surveys show that health care is a growing concern for military families. Convincing them to stay in the service may be harder when they might be ordered to go live in a health care desert.

About the data:

Military base locations came from the Military Installations, Ranges and Training Areas (MIRTA) dataset produced by the Department of Defense. This data includes DOD sites in the U.S., Puerto Rico and Guam that are larger than 10 acres and have a facility replacement value of at least $10 million.

Primary care and mental health care shortage areas came from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s shortage designations. These health professional shortage areas (HPSAs) are identified by state offices and approved by the federal agency. The shortage areas used in this analysis were geographic HPSAs, meaning the shortage is for the entire population within the designated area. An HPSA designation takes into account travel time to the nearest source of care in addition to other factors.

Maternity care shortage areas came from the March of Dimes. The areas used in this analysis were areas designated as “maternity care deserts” or areas with “low access to care.”