Trees are gaining ground in the Arctic as a result of climate change. A group of scientists studying tree cover in Alaska’s Brooks Range found that trees are expanding north and at higher elevations, in part due to the loss of Arctic sea ice, which is disappearing because of human-caused global warming.

When sea ice retreats, large areas of open water are left in its place. Warm conditions speed up evaporation, leading to heavier snowfall on nearby land, said Patrick Sullivan, director of the Environment and Natural Resources Institute at the University of Alaska Anchorage.

“You basically have this blanket of snow that covers up small seedlings and saplings, and protects them,” he said.

That thicker snow layer is making it easier for trees to survive in harsh Arctic conditions.

“In the winter in the Arctic, the wind picks up all of these spiky snow crystals, and basically batters trees and other vegetation that stick up above the snow,” Sullivan said. “And so the deeper the snow, more of the population gets protected.”

Sullivan said snow also serves as an insulator, keeping the ground warm enough that soil microbes can continue to churn out nutrients for growing trees.

Permafrost thaw, another effect of climate change, is also at play, said Sullivan. The thick, insulating layers of snow are speeding up the thaw, making it easier for trees to take hold in the soil and grow.

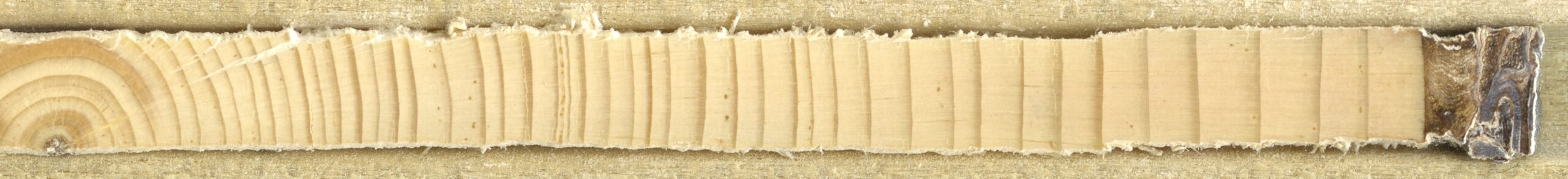

Rapid growth in white spruce trees can actually be linked to periods of open water at sea, said Colin Maher, a postdoctoral fellow at UAA who studies tree rings.

“If you look at the tree ring measurements, you would see an increasing trend in ring widths. They start kind of small, and then they get bigger and bigger. And that’s what the open water looks like as well,” Maher said. “It’s increasing rapidly.”

Roman Dial, a math and biology professor at Alaska Pacific University who co-authored a recent paper on tree line expansion in Science with Sullivan, Maher and other researchers, studied satellite imagery from around the circumpolar north and found that the tree line is advancing in many parts of the Arctic.

Dial said this shift in the Arctic ecosystem isn’t limited just to trees – animals like moose, beavers, black bears, and even salmon are moving north too. The availability of the subsistence animals that many communities rely on is also changing.

“What does that mean for people who live there? It’s hard to say,” Dial said. “It’s a change. You can talk to people in Kotzebue, and they’re excited about the huge chum salmon runs that they’re getting, but they’re kind of bummed out that the caribou populations are crashing.”

Dial said it also remains to be seen how increased tree cover will affect the climate. Trees serve an important role as a “carbon sink,” storing carbon dioxide, which is a major driver of global warming. But at the same time, dark trees like spruce soak up sunlight instead of reflecting it back the way bare, snowy tundra does. Dial said trees trapping heat like that could speed up Arctic warming.

Kavitha George is Alaska Public Media’s climate change reporter. Reach her at kgeorge@alaskapublic.org. Read more about Kavithahere.