For the Aaluk Crew, last Wednesday was cooking day.

The night before, the whaling crew, captained by Bernadette and Quincy Adams, had landed the first bowhead whale of Utqiaġvik’s spring season. The crew flag, featuring a harpooned bowhead tail framed by a sunset, waved above the Adams’ two-story home, signaling the successful hunt.

The garage door rolled up and steam flooded out into the yard.

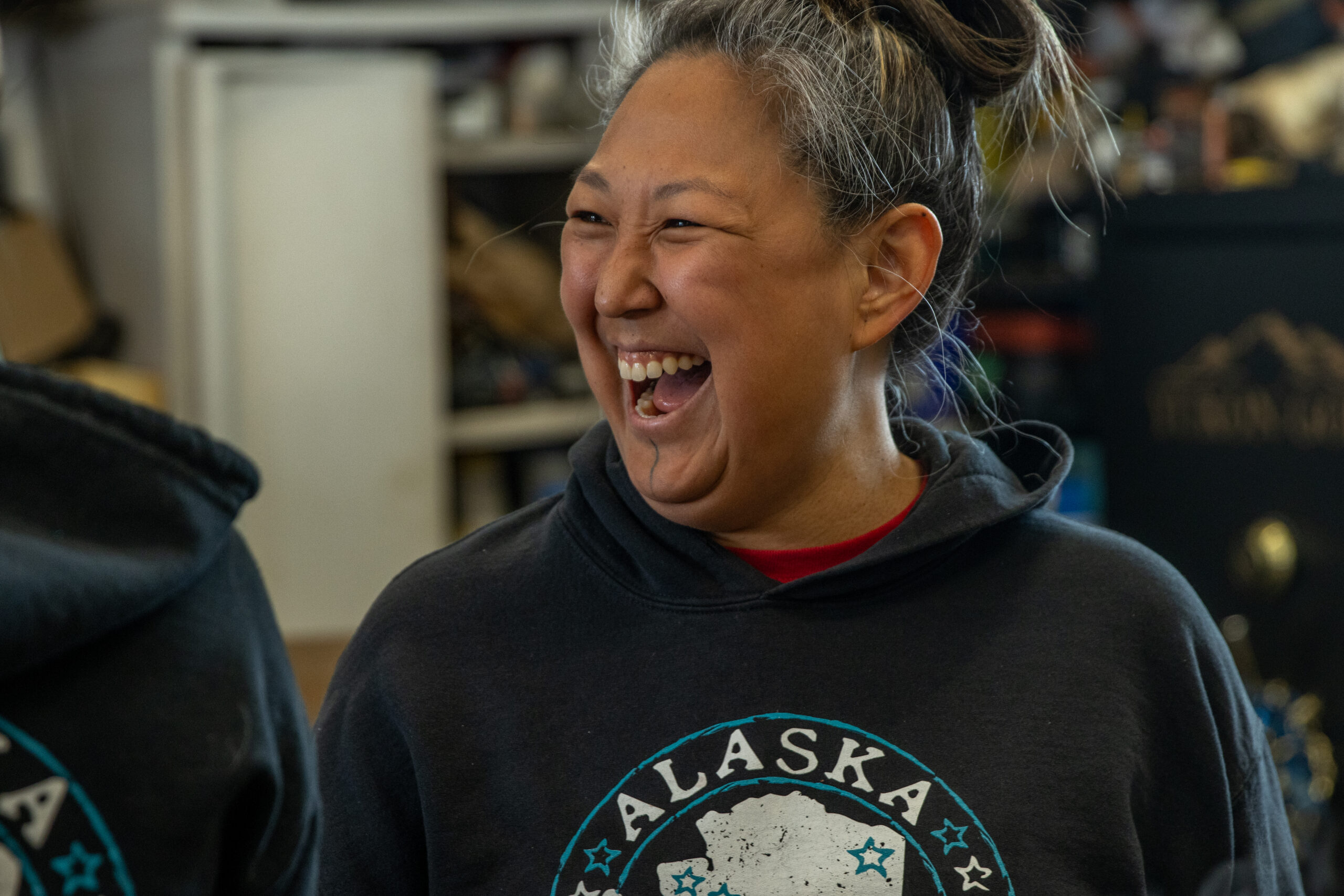

Inside was a picture of a jubilant chaos. Late 2000’s pop music blasted from a bluetooth speaker as crew members and family bustled between huge pots, tending to different cuts of meat — boiling slices of bowhead blubber and skin, or uunaalik, heart, tongue and intestines.

Children ran underfoot, people fed babies tiny pieces of cooked meat. A husky named Avvaq sat tied up in the snow, hoping for scraps. Laughter ricocheted off the walls. Everyone buzzed with excitement for Utqiaġvik’s first spring bowhead.

“Whaling brings so much joy,” said Natasha Itta, a member of the Aaluk Crew.

Meat from this catch will feed the crew and their neighbors for months to come. It will also be sent to other North Slope villages and even family in the Lower 48.

“The bounty just goes all over the place,” Itta said.

For Inupiat communities on the North Slope, bowhead whaling is a central part of spring. But climate change is adding an extra element of uncertainty to the whaling season.

Warmer temperatures are driving a decline in the region’s sea ice, which is forming later in winter and thawing earlier. Whalers say the shorefast ice, or the ice still attached to the coastline at this time of year, is becoming thinner and less predictable. That poses an extra challenge — and possible danger — for crews, who must cross the ice to reach open water and then rely on it when they pull in whales that can weigh more than 60 tons.

Itta said a possible future without stable ice and successful spring hunts is scary to think about.

She said whalers are thinking about how to adjust if the shorefast ice won’t support spring whaling in the future, like potentially going out earlier in the season when the ice is firmer — but then there’s a risk that whales won’t be migrating yet.

“It’s going to take a lot of adapting,” Itta said. Traditionally, bowhead whaling starts in late March or early April, with feasts and festivals following in the summer. Losing that rhythm would be hard, Itta said. “It’s almost like you lose a piece of your identity. Because that’s who we’ve always been, that’s who we’re going to be.”

But this season is already a success. It also marked an important milestone: the 31-foot-whale caught by the Adams crew was landed by 17-year-old Donald “Button” Adams — his first as striker.

Donald is the son of the Aaluk Crew captains Bernadette and Quincy Adams. He’s not one to brag.

“I don’t know. It’s pretty cool,” he said with a shrug, in a crowded kitchen.

But his parents couldn’t hide their quiet pride.

“It’s a big deal. He’s been working really, really hard,” said Bernadette Adams, Donald’s stepmom. In 2014, Bernadette became the first known woman from Utqiaġvik to land a bowhead.

Donald has been going out on the ice since he was seven years old, learning from his parents: “What to look for on the ice, when to go out, when not to go out, which way the wind direction is going,” he said.

For several years, he’s been training to take on the role of striker from his father, Quincy. The striker stands in the bow of the boat and launches the darting gun to harpoon the bowhead.

On the night of the successful hunt, the crew set out just before midnight, Donald said. They prayed with the boat and then launched it from the ice.

“The water was pretty flat, almost glass,” he said. “Then we saw a whale along the tuvak — that’s the edge of the ice where the ice and the water meet.”

That first whale quickly disappeared. But soon, the crew spotted another one, about 300 yards out. As they sped towards the second whale, Donald said, they saw it spout just 20 feet away, and closed in to where they expected it to surface next.

“Sure enough, right beside us the whale popped up,” Donald said. He threw the harpoon. “It was a good shot, too.”

Experienced hunters themselves, Donald’s parents know what it takes to be a successful striker.

“We told him you gotta show us you can do it,” Bernadette said. “We made him go and help cut multiple whales. ‘You got to ask questions,’ I said. ‘It’s not just from us you’re gonna learn, it’s from everybody else.’”

Donald was ready to serve as striker last fall — until he broke his leg in an accident on the boat. Just then, the crew spotted a whale. Despite his broken leg, Donald refused to let them turn around, Bernadette said.

“He was like ‘just go after it!’” Bernadette recalled.

Quincy said it’s hard to express how it felt to watch his son take on this new role.

“I don’t have any words for that,” he said. “I don’t have any words for watching that happen. It’s just so humbling to see.”

The crew towed the 32-ton whale back to their camp and heaved it onto the ice with the help of snow machines. It took about 40 people another six hours to process the catch to bring into town, Donald said.

In the garage on cooking day, teenagers darted in and out with massive sheet trays, sliding batches of cooked meat into plastic totes lined with trash bags to share with anyone from the community who stopped by.

In the yard outside the Adams’ house, big chunks of meat lay scattered in the snow, waiting to be processed. Quincy and a few other men cracked jokes while they portioned out cuts for crew and family.

Whaling is about providing for others, Quincy said.

“It’s just built in us. It’s something that we yearn to do,” he said. “If we’re not successful, then we find other ways to feed the community. But doing this and feeding the community is what it’s all about.”

This first bowhead was an auspicious start to Utqiaġvik’s spring whaling season. Since last week, crews have caught five more.

Kavitha George worked at Alaska Public Media from 2021 to 2024. Her coverage areas included statewide politics and climate change.