Timber sales in Southeast Alaska’s Tongass National Forest often spark conflict between environmental groups, the timber industry, and the U.S. Forest Service. Timber companies want more opportunities to harvest, and environmental groups want to protect the forests. But a new sale near Petersburg focusing on second-growth trees has all those groups on board.

The sale design is the result of the Forest Service changing its public process over the years.

Brett Martin has owned a small sawmill for 35 years. He lives part-time in Petersburg and part-time in Sitka and loves making lumber out of Southeast trees.

“Two by fours, two by sixes, fenceposts, fencing…,” Martin said. “Anybody who’s ever sawn logs into lumber, you know, it gets into your blood, and it’s something you really enjoy.”

Martin considers himself one of several small cottage industry mills in the region. He’s also been a logging engineer for three decades, contracting with the Forest Service and private companies to inventory forests for possible harvests.

He has seen timber sales dramatically decline in the last few decades, devastating the region’s industry. Employment went from the thousands – when logging old growth was common practice – to less than 300 workers a few years ago.

There is only one remaining larger-sized timber company in the region – Viking Lumber Co. on Prince of Whales Island. They have the necessary infrastructure to harvest trees in very remote places. And Viking has sustained its company by shipping logs out of Alaska in the round to be processed somewhere else. Martin says that means Alaskans must import their lumber.

“Most of the lumber that’s used for oh, construction purposes in Alaska, a lot of it shipped up from the Lower 48, if not most of it,” he said.

But Martin sees an opportunity to keep more lumber in Alaska with the Forest Service’s shift from old-growth to young-growth timber sales. The Tongass has 17 million acres of forest and Martin says up to 450,000 acres is young growth or second growth, meaning it’s been previously logged. It’s those young trees that the Forest Service wants companies to harvest while preserving the old-growth stands.

Ray Born, Forest Service district ranger based in Petersburg, is helping to manage the new timber sale in Thomas Bay.

“There’s certain old growth areas, we’ll just leave alone,” Born said. “We’re gonna leave them, you know, for wildlife or for old-growth characteristics or things like that we want to maintain over time.”

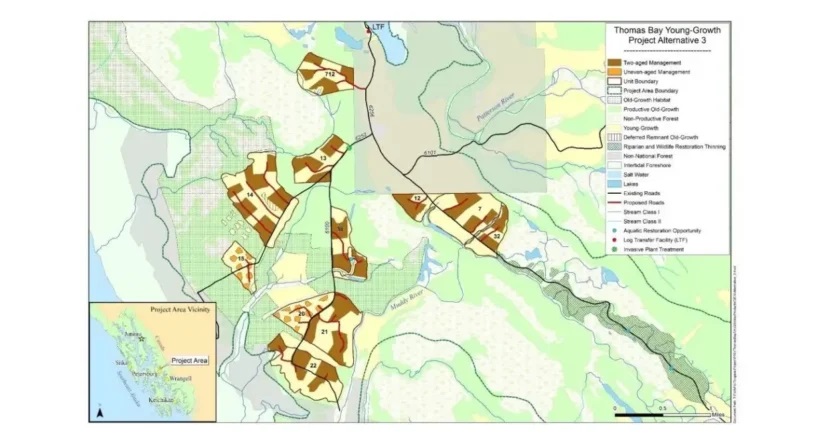

The initial Thomas Bay timber sale proposal was for about 22 million board feet, mostly clear-cut. After a few years of public process, they shrunk the harvest to 12.6 million board feet to be harvested through a patchwork of areas over several years.

Thomas Bay has been logged to varying degrees from the 1930s through the 1980s. The Forest Service still considers it a productive area, with the ability to regenerate harvestable trees in 60 to 80 years. Born says there could be continuous harvests if it’s done piecemeal.

“So the intent is we’ll do some now, and 20 years down the road, we’ll do some more, 20 years down the road, we’ll do some more and in about 80 years, come back to where we started at,” Born said.

Harvesting smaller areas over time could be better for wildlife and it could allow small sawmills more opportunities. Those are comments the Forest Service has heard during the public process leading up to the sale. Born has been working with the Forest Service for three decades and says a lot has changed in how they approach timber sales.

“It’s more listening. We’ve listened more carefully to all the people who have an interest in it now and it’s more holistic,” Born said. “And that’s kind of one of the unique things about the Forest Service, you know, we focus on serving the people and caring for the land – it’s that balance there that makes it really interesting, and we spend more time listening to the people now.”

And they did listen to people, according to Katie Rooks with the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council.

“I actually have lots of good things to say about the Forest Service in relationship to this particular timber sale,” she said.

The Southeast Alaska Conservation Council often opposes timber sales but they see the Thomas Bay one differently.

“This feels like a different timber sale,” said Rooks. “Instead of going for the obviously most profitable alternative, they do create a pretty decent balance between providing some timber and wildlife habitat.”

Rook’s group isn’t anti-timber but they are against clear-cutting old growth – they believe it’s bad for the trees and the wildlife. The Thomas Bay sale’s environmental assessment considered the impacts to deer, moose, wolves, marine mammals, salmon, and birds. Rooks also supports the federal effort to break up the acreage over time, catering to smaller sawmills.

“To be able to somewhat create a market for this timber and to process it here locally as much as possible into a higher value-added product,” Rooks said.

That’s exactly what small sawmill owners like Brett Martin are interested in. He has a vision to expand his company and provide building materials for Southeast residents and businesses. He also wants to sell cabin kits from the local wood.

“I can hire 14 to 16 guys full-time, and that’s just in my sawmilling side of it,” Martin said. “I truly want to start a construction side of it, which would then allow us to, you know, start building cabins because people will come, they’ll want to buy a kit, and then the very next question out of their mouth is going to be, ‘Do you know of anybody who builds them?’ I could potentially hire, 20 to 25 people full-time.”

To accomplish his business goals, Martin would like to buy two million board feet of timber a year for the foreseeable future. But first he has to win the bid for the Thomas Bay sale, which the Forest Service plans to open in early fall.

The Forest Service plans to start marking the area in April.

While big equipment is at the Thomas Bay site for logging, the Forest Service plans to restore habitat that’s been damaged from past timber sales. Back in the 1950s and 1960s logging in Southeast was often short-sighted. Projects left behind infrastructure that affected fish migration, such as culverts that later became blocked. Or they logged up to the water’s edge, damaging fish rearing habitat. The Forest Service also plans to treat invasive plant species while they’re at the site.