The discovery of baby dinosaur bones on Alaska’s North Slope has paleontologists rethinking the animals’ lives and physiology.

University of Alaska Museum of the North director Pat Druckenmiller and colleagues from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and Florida State University made the discovery along the Colville River.

Druckenmiller said the area of eroding bluffs has yielded many dinosaur fossils over the last couple of decades. But these bones are different.

“Tiny little baby bones and teeth, not of adults and juveniles, but of actual very, very young animals that died either in the egg or just after they hatched,” he said.

[Sign up for Alaska Public Media’s daily newsletter to get our top stories delivered to your inbox.]

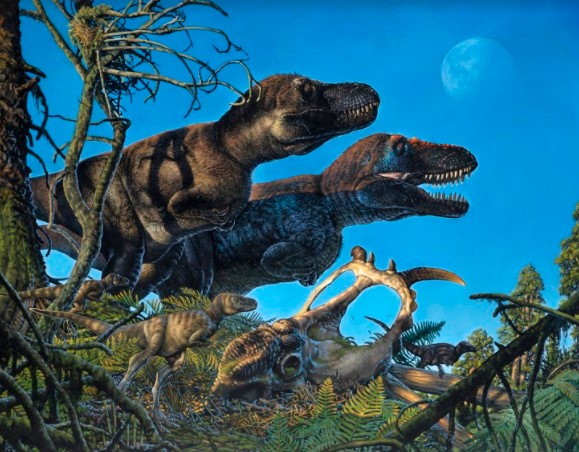

The baby dino bones were found in sediments collected by University of Alaska Fairbanks and Florida State University scientists. They ranged from those of small bird like animals to giant Tyrannosaurus. Druckenmiller said the discovery of the baby dinosaur bones so far north indicates year-round residency.

“Dinosaurs likely had incubation periods upwards of five to six months for some species. And if that’s the case, a dinosaur laying its eggs in the spring would have been hatching them late in the summer,” he said.

If dinosaurs were migrating, they would have had very little time to move to lower latitudes with newborns, which suggests that the animals did not, in fact migrate.

“We think it’s more likely they actually managed and adapted to living in the Arctic conditions, year-round,” he said.

Given that the site where the bones were found was closer to the North Pole 70 million years ago, Druckenmiller said even in that era is warmer climate, the dinosaurs endured pretty extreme conditions.

“Yes, it was cold. Yes, it was freezing conditions and probably snow. But at 80 to 85 degrees north you have to deal with three to four months of continual winter darkness. That’s the kind of world we don’t generally envision dinosaurs living in,” he said.

Druckenmiller said living in such relative cold is also telling about the dinosaurs physiology.

“If you lived up there year-round, you almost certainly had to have made your own body heat and probably maintain some elevated internal body temperatures and that’s that in a nutshell is warm-bloodedness,” he said.

Druckenmiller said that adds to evidence from other studies pointing to warm-blooded dinosaurs. Findings from the study are published in the journal Current Biology in an article authored by Druckenmiller, Florida states Gregory Erickson, and Jaelyn Eberle of the University of Colorado.

Dan Bross is a reporter at KUAC in Fairbanks.