Sitkans paid their final respects last week to Herb Didrickson.

The 91-year-old Tlingit elder died in Sitka on September 25. In many ways Didrickson was everything you’d expect of a man of his generation: A 1946 graduate of Sheldon Jackson High School, who married his sweetheart Pollyanna. He subsequently earned an Associate of Arts Degree from the college of the same name. He spent 30 years working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs as an Industrial Arts instructor at Mt. Edgecumbe, coaching sports and refereeing basketball.

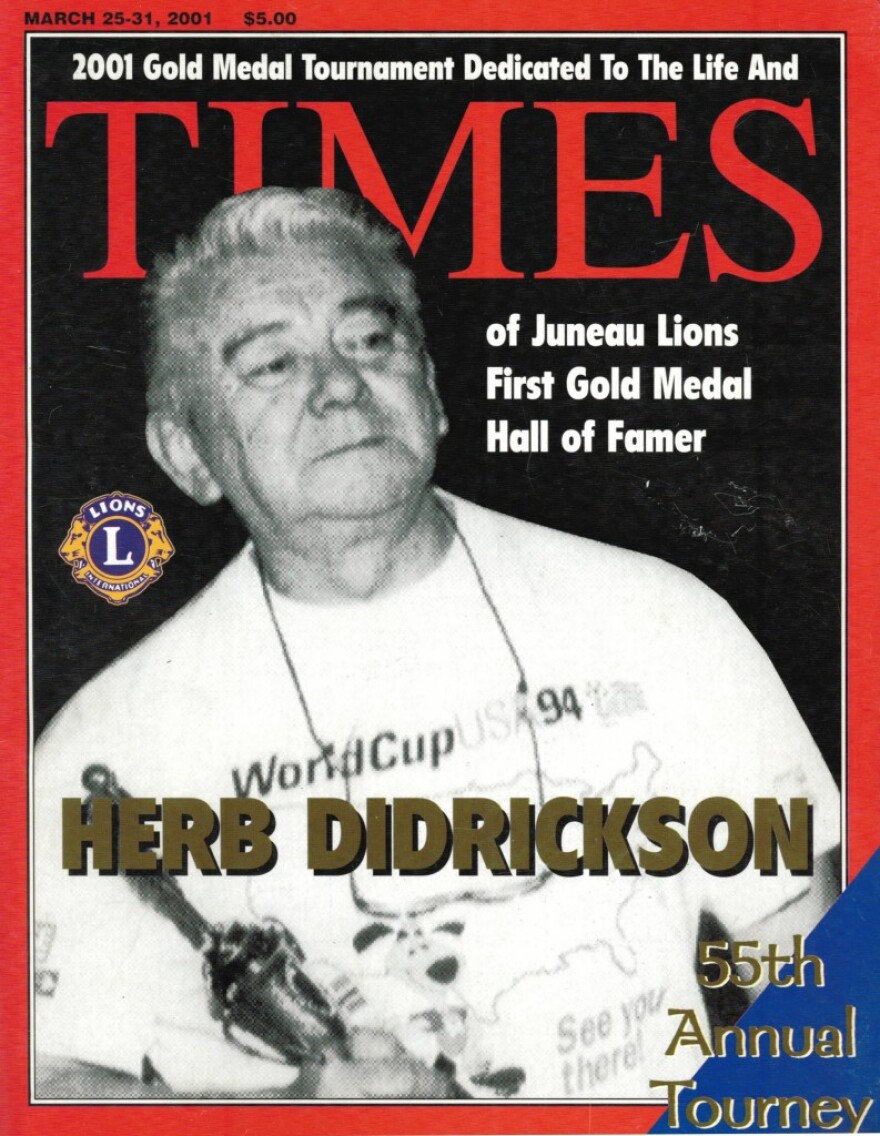

But Didrickson was also something most can never claim to be: The greatest athlete ever produced in Alaska.

The stories have always sounded like myths. As an older man, Herb Didrickson would be in the stands cheering on the Mt. Edgecumbe Braves.

Invariably someone would point to him and tell point out that Didrickson had been a huge star in his day, and that at 5’10” he could dunk a basketball from a standing jump, and maybe bump his elbows on the rim.

Yet people who saw and played against Didrickson in his prime don’t dispute any of the stories.

Gil Truitt was just a couple of years behind Didrickson in school.

“He had the ability in all sports — things coaches tried to teach, to Herb came naturally," Truitt said. "He didn’t have to work hard, but I never knew anyone who worked harder in any sport than Herb. He was continually trying to improve himself as an athlete.”

Didrickson honed his skills as a student athlete against the big military teams stationed in Sitka during World War II. He averaged around 30 points a game in his student days. Later, playing Gold Medal Basketball for Sitka’s ANB team, Didrickson’s average dropped, as he developed his mastery of the assist, and a style of basketball that would later become associated with NBA greats like Larry Bird and Magic Johnson.

“There’s not a team in America — not a team in America — he wouldn’t have started for as a point guard,” John Abell said.

Abell is also something of a basketball legend. Growing up in Sitka he watched Didrickson play Gold Medal. Abell graduated from Sitka High in 1954, and went on to play for Oregon State University, and eventually coach for the 1964 Olympics.

“I’ve seen worldwide athletes, worldwide basketball players. And it can be etched in stone that I never saw a basketball team at any level that Herb Didrickson couldn’t have played for," Abell said. "As a point guard, Herb Didrickson was 40 years ahead of his time.”

In 2012, Abell and Truitt nominated Didrickson for the the Alaska Sports Hall of Fame. Didrickson was already in the Gold Medal Hall, as well as the Alaska High School Hall, but he was never really tested outside of the state. It was important to frame Didrickson’s nomination against other inductees like Carlos Boozer and Libby Riddles.

"I look around and I see players now at the college level, and there isn’t any doubt in my mind that he would have been able to play with them in today’s game. That’s a big statement, I understand that," Abell said. "I’ve watched him, and year after year I would see things develop, and I’m thinking, “My gosh, I saw Herb do that back in the 50s!”

Gil Truitt said that Didrickson and his teammate Moses Johnson perfected what they were calling the “lob pass,” but is nowadays referred to as the “alley-oop.” Basically, a player sprints for the basket and jumps, just as his teammate has lobbed up the ball. Done right, it results in a dunk, or an elegant tip-in.

Although Didrickson was only 5’10”, Truitt said he could do either.

“Standing under the basket he was able to jump and dunk the ball from a standing position," Truitt said. "And he did mention that he bumped his elbow on the rim a few times.”

But despite the sheer physical prowess, Truitt argued that Didrickson brought many gifts to the game: He was an extraordinarily quick ball handler, often the fastest person on the court. He had long arms and defensive instincts that made him impossible to challenge. Truitt remembers opposing coaches instructing their players to turn and pass the ball anytime Didrickson came near. And there’s this: Win or lose, he’d visit the other team after the game in their locker room to congratulate them.

Unlike many athletes of the era, Didrickson’s career was not interrupted by war.

"Personally, I thought Herb had a great life and family. And he enjoyed where he was living," Abell said. "And remember they didn’t have — especially professionally, hell, I knew (Jim) Barnett, he got $4,200 for going to the Warriors — they didn’t have the big bucks they have now. If they had seen Herb in today’s market and said, 'Herb, you know, x-number of millions…' it wouldn’t surprise me at all if Herb said, 'Thank you. That’s very generous. But I’m happy where I live. I’m happy with my friends here, and I don’t want to give that up for money.'"

While college is a stepping stone to pro basketball, it’s not for other sports. The Alaska Sports Hall of Fame said the Seattle Rainiers minor-league baseball team also made an unsuccessful attempt to recruit Didrickson to be a centerfielder.

Just one more reason, according to the Hall of Fame, that it considers Didrickson to be “the Jim Thorpe of Alaska.”