What brought Soviet Russia and the U.S. together during the Cold War? Walruses.

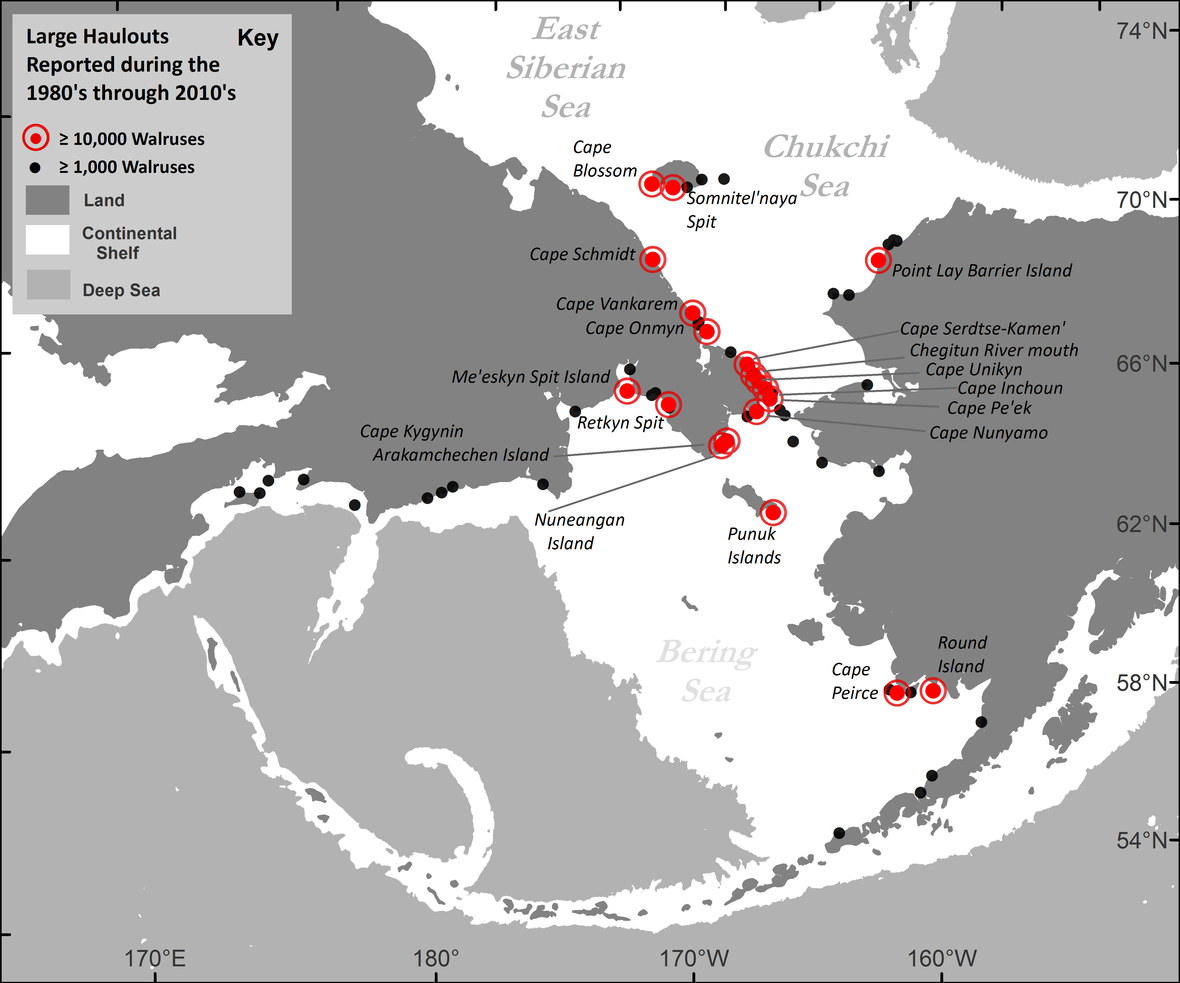

Now a new federal database, created with over a century of information, shows where those animals haul out on both sides of the border. And that’s especially important as sea ice disappears and the animals spend more time on land.

Tony Fischbach says a cacophony of walruses has a lot of bass.

“There’s so many animals there. It really reverberates in your chest, especially when you’re laying in the sand,” he said.

Fischbach is a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. He’s describing listening to more than 10,000 walruses on the beach in Point Lay. When he’s in the field, Fischbach dresses up in an outfit that looks like beach debris to sneak up on the animals to radio tag them.

He says, not too long ago, this spot looked different.

“Well, prior to 2007, we’ve never had large numbers of walruses on the North Western Coast of Alaska,” Fischbach said.

That’s when the sea ice disappeared off the continental shelf of the Chukchi Sea. In the summer, female walruses and their babies spend time offshore hauling out. They float on sea ice to a walrus version of the grocery store, an area full of nutrient-dense food like clams.

But with the melt, they’ve had no choice but to come onshore.

“When they’re onshore, if they get moving, they can develop into a panic, and there can be trampling, injuries and deaths,” he said.

Fischbach says he’s encountered over 100 walruses who died like this, mostly babies.

But this isn’t the only time in history biologists have been concerned about the Pacific walruses. In the 1960s, Fischbach says commercial overharvesting — not melting sea ice — was seen as a potential danger. And to get an idea about walrus population, the United States had to team up with an unlikely ally.

“Even the Cold War was not able to stop this work from happening,” said Anatoly Kochnev in Russian.

Kochnev is the coauthor with Fischbach on the Pacific Walrus Coastal Haulout Database, which holds 160 years worth of information. It’s a historical treasure trove — from old ship logs to joint aerial surveys that happened before the fall of the Soviet Union. Our countries go way back on working together on walrus.

“Walruses are not political and do not respect any political boundaries,” he said.

Knowing that, Kochnev says Russian and American scientists agreed to work together. Our countries collected and shared information on walruses that could shape policy decisions today. All of this when Russia was still a ruled by a Community party.

“In the Soviet era, financing was provided to the scientists and that was provided to do the aerial surveys by plane, and the last one of those was in 1990, and that was the last year the Soviet Union funded the surveys,” Kochnev said.

Since then, Kochnev says Russia has been through some tight economic times, and the funding for projects like this has largely dried up. So, I ask, how is he able to spend months at a time in remote parts of Russia studying walruses? My translator, Elisabeth Kruger, responds to his answer with a laugh.

“He says I know myself how he finds money, and that I don’t need to ask him,” Kruger said.

She works for the World Wildlife Fund. The organization helps pay for Kochnev’s research.

Remember Point Lay — the spot where Tony Fischbach observed over 10,000 walruses hauling out? Just across the Bering Strait is Cape SerdtseKamen’. Kochnev has documented more than 100,000 walruses hauling out there.

And over the years, he says he’s witnessed the effects of climate change firsthand. Polar bears attacking and killing walruses. Something he says biologists hadn’t observed at the haulout before. Just recently, they’ve seen evidence of walruses eating birds.

“That could be an indication that they are finding it more difficult to find food,” Kochnev said. “And that their normal food source is not enough. The walruses predating on birds happened 30 years ago, but it was very rare. Now we’re starting to see it more often.”

Both Kochnev and Fischbach say they hope the haulout database can help illuminate what’s happening to the Pacific walrus. Next year, the feds will decide if the animal should be on the endangered species list. And the database has already received attention from a private company that advises the industry on oil and gas.

Fischbach says the database couldn’t have happened without decades of scientists working across the Bering Strait.

“Even down to the small details,” Fischbach said. “I was having trouble working with the Russian language, representing the Russian script in the database because it’s in Cyrillic. And I’m using Latin script, and the complexity of that on computer systems is really daunting.”

And a Russian scientist — who wasn’t even working on this project — put in the time to lend a hand.