With warming ocean temperatures, the risk for paralytic shellfish poisoning can linger all year round. And Alaska has only one FDA-certified laboratory to test shellfish. There are no labs to protect those digging for their dinner, but that may soon change.

At the end of the month, the Sitka Tribe of Alaska will open an environmental research laboratory and – with all hope – take a bite out of the testing market.

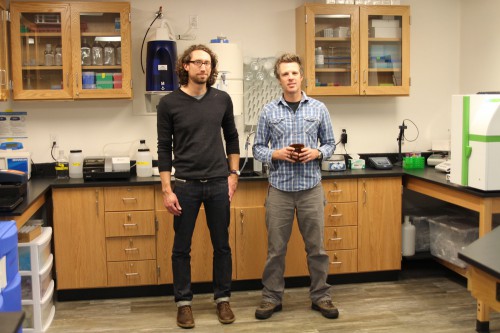

This time last year, the room in the corner of Sitka Tribe of Alaska’s (STA) Resource Protection Department was bare. And now, it’s got a fume hood, test tubes in every color, and a $49,000 machine.

Michael Jamros is the lab’s new manager. And the “robot” in question is a plate reader, one of several machines that can analyze toxins in shellfish. After the shellfish arrive, Jamros shucks all the meat out and puts it in a blender to homogenize it. He then extracts the toxins and removes the solids using a centrifuge.

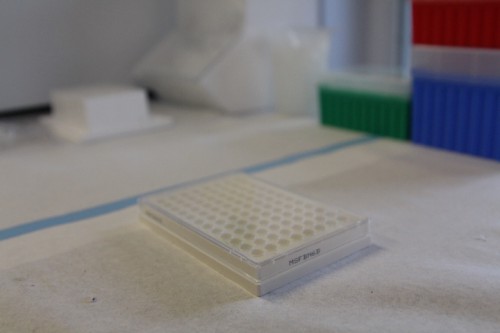

Using a pipette, Jamros will dispense the solution in 96 tiny wells on one plastic plate. Imagine filling a tray with batter for 96 muffins, but instead of putting it in an oven, he feeds it into a plate reader.

Jamros is running an ELISA assay, measuring the toxicity of each well. The results appear on his laptop. “From here we have our data that we can calculate from and figure out how much toxin is in our samples,” he said.

You hear that? Data. Cold, hard numbers that take the guesswork out of eating butter clams or blue mussels. In Southeast, there’s never been a way for subsistence harvesters to assess the risk of paralytic shellfish poisoning or measure harmful algal blooms, or HABs, which load shellfish with toxins. Until now.

Chris Whitehead is STA’s environmental program manager and the driving force behind the lab, set to open in May. “Native people have been harvesting clams for thousands of year. A lot of the elders I talk to don’t do it anymore because they just don’t know. So, to be able to bring that back and be able to utilize that resource is huge,” Whitehead said.

When he came to Sitka in 2013, Whitehead wanted to create a warning system for clam diggers, like in Washington state. “The Washington Department of Health has a great website so you can see what beaches are open or closed. And when I got to Alaska there wasn’t anything.”

Whitehead called up Alaska’s Department of Environmental Conservation, which tests all commercial shellfish for the state. He discovered, however, there would be a time lag to ship shellfish to Anchorage and await results. “The turnaround time for the [DEC] data – to actually be usable for us and to prevent human health issues – wasn’t going to work,” he said.

Given this, Whitehead decided to pursue a local solution by creating his own marine biotoxin program right here in Southeast. He locked in $1 million in grant funding for the next three years. He formed Southeast Alaska Tribal Toxins (SEATT), a coalition of thirteen other tribes in the region and organized trainings for them with state and federal agencies, like NOAA, to be “eyes in the water,” monitoring local beaches for toxic blooms.

“So those sites will be monitored at the expense of the tribe and the resources that the tribes have every other week. So every tide cycle pretty much,” Whitehead said.

Jerry Borchert was in Sitka to lead one of those trainings. Borchert coordinates marine biotoxin management for the state of Washington.

In speaking with KCAW, he said, “My first time here was a year ago in September. It was a smaller group. I think there were six tribes at the time and for a lot of these folks, this was brand new to them. Looking at plankton, trying to identify what a harmful species looks like, how to record it, how to share this information, and it’s those same tribes in the beginning who are now the teachers and the program is expanding. This is amazing.”

With the new laboratory, subsistence harvesters can hopefully send their shellfish to Sitka and get test results back in one business day. Eventually, the lab hopes to run tests for commercial entities – like shellfish growers and processors.

But some hurdles remain. The lab needs the blessing of an alphabet soup of agencies, like the FDA, to become a full-fledged regulatory lab, on par with the one on Anchorage. Borchert said, “Long term stability is something I’m a little concerned with. The state regulatory folks are finally coming to these workshops and I’m hoping they can recognize what can happen.”

For his part, Whitehead is taking it one step at a time. The lab is running test samples all this month and sending their results to NOAA in Seattle, for verification. If those check out, the lab will begin accepting subsistence shellfish as early as May.