While police issues continue to divide communities and make national headlines, the Sitka Police Department is trying to restore confidence locally, after disturbing video from the Sitka jail surfaced on social media this fall. Police officers and community members convened to talk about troubling points in the case — like the fact that one of the officers involved had previously been involved in a fatal tasing event in New Mexico.

The department’s top officers recently gathered with tribal leaders and other Sitkans in a town hall meeting to discuss the incident, and to share information about the department’s guidelines regarding the use of force.

About 35 people attended the 3-hour meeting.

The town hall meeting was the kind of conversation that many larger communities should probably have, but can’t, because the scale of the acrimony and tension over policing issues in recent years has grown too large for a single room.

But Sitka has a just-rightness that allows people to speak, and a cultural tradition of courtesy that allows people to be heard.

Sitka’s police force has undergone some recent changes as well. Officer Mary Ferguson, a Tlingit citizen and newly minted graduate of the Law Enforcement Program at the UAF Career and Technical College emceed the meeting. Two relatively new lieutenants, Jeff Ankerfelt and Lance Ewers have years of experience, but share an attitude about public engagement that feels fresh.

This is Lt. Ewers, speaking about the department’s renewed push for body cameras on officers:

“These things are great because they’re completely non-biased witnesses to events that take place. It’s a beautiful thing, being able to video-record everything the officer does.”

Body cameras were on the agenda, along with recent cemetery vandalism, and the department’s newly implemented taxi-voucher program to reduce holiday drunken driving arrests.

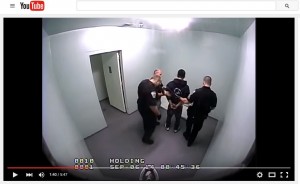

But none of these topics could match the gravity of the tasing incident in Sitka’s jail. A video of the 2014 arrest of then-18-year-old Franklin Hoogendorn went viral when it was posted on social media this fall by a Sitka teacher.

Hoogendorn is an Alaska Native from Koyuk. He was attending Mt. Edgecumbe High School at the time of the event.

The video was obtained through a court order requested by Hoogendorn’s defense attorney.

Lt. Ankerfelt nodded to it in his discussion of body cameras. He asked, who owns the video files of police activities?

“One of the things we’ve struggled with locally is that someone will have an encounter here with a police officer and they’ll get on social media — Sitka Chatters or Sitka Chatters Without Rules, these different places — and they’ll discuss what they feel happened. But if you watch the video, it’s something entirely different. Meanwhile strife, conflict, disinformation — to some degree — is occasionally spread. But there’s this information that is essentially publicly-owned.”

Ewers and Ankerfelt explained that pressure to finally release the Sitka Police Operating Procedures Manual — and to have the town hall meeting — came from within the department.

Alaska Native Brotherhood president Tom Gamble applauded the efforts of the police to improve transparency. And he spoke candidly about his own experience, echoed by other tribal citizens at the meeting.

“The thing about growing up in Sitka as a young Native person is that you see those uniforms, and it’s very intimidating. Some of that, as we age, just never goes away.”

Nevertheless, Gamble remained open on the issue of the Hoogendorn video. “I can’t say the video was wrong,” he said. “I wasn’t there.”

The Sitka Tribe of Alaska wrote a letter to the FBI asking the agency to examine bias against Alaska Natives in the Sitka police department. The personal stories of several other tribal citizens like Stephanie Edenshaw and Bob Sam, suggested that relations between police and the Native community in Sitka have been difficult at times.

But Alaska Native Sisterhood president Paulette Moreno believed that this meeting, and the willingness of the officers present to speak openly about their interest in regaining trust, meant that times had changed.

She referred to police chief Sheldon Schmitt.

“I know he’s a good man, and he wears a badge here tonight. And I know in my heart that if he had seen — in his experience — a Native person who was treated unkindly by an officer or by a police department, or treated unfairly, that he would do everything in his power to stop it at that point. And I know a lot of people here have been treated unfairly. I know that there’s a history in the Indian village, a history among our women, and other incidents with our elders and their sons and their families. And I just want to say that we feel your tears.”

Schmitt responded it was important to address systemic prejudice in policing.

“I know in my heart that there’s been injustice in this community and in this state toward Native people. And I know that influences how people feel about the police. Even if it’s not that police officer, or me specifically.”

Many in the room used Chief Schmitt’s words as an invitation to share their personal — and sometimes painful — stories of police encounters. Elder Nels Lawson said that this was the purpose of the talking circle.

But the discussion never drifted too far from the Hoogendorn video. The audience asked about the hiring policies of the police department, and whether the city knew that one of the officers involved in the Hoogendorn incident had been involved in a fatal tasing in New Mexico.

According to court records, the public defender agency obtained detailed personnel records of one of the officers who arrested Hoogendorn — Jonathan Kelton — who was involved in a fatal tasering incident in Roswell, New Mexico in 2013. The victim in that incident, Cody Towler, stopped breathing after being tased in a violent encounter with police. Although the death was ruled a homicide, Kelton and his fellow officers were exonerated when autopsy reports showed evidence that Towler’s health was severely impaired by drug use.

They also asked about the taser, how it’s used and how often it’s used.

Lt. Ewers explained as much as he could without going into specifics of the Hoogendorn case, which might be headed to court.

But not everyone was satisfied. Brent Turvey is a forensic investigator who came to Sitka 15 years ago, and has since made the community his home.

“I hear what you’re saying. But I have a very real concern that you don’t understand that what actually happened was wrong. Because what I hear is, ‘We’re gonna do this, we’re gonna do that.’ But do you actually understand that that kid being tased that many times with three officers piled on top of him, in a situation he couldn’t respond to — under circumstances of being held by police — that that was wrong? Because the community understands it’s wrong.”

Turvey has been a frequent and vocal critic of police practices on social media. He said he supported the department’s efforts toward transparency.

Lt. Ankerfelt, however, thought social media had created antagonism toward officers. Some of those feelings came out in this exchange with Turvey.

“We don’t pay them very well. Collectively we don’t treat them very well. OK? They risk their lives. And they go home and talk about the things they read on the internet that affect their children. We are getting death threats right now against our officers. I got a call a couple of days ago from a guy who says he’s going to come into my driveway.”

“Are you saying you can’t tolerate a public dialogue about facts that are available to the public, because your officers’ feelings might get hurt?”

The FBI has not said how it will address the tribe’s letter on racism when agents arrive in Sitka this month to investigate the Hoogendorn incident. Nevertheless, there was sentiment among some elders at the town hall meeting that it had been productive, and that open dialogue with police should happen more often.

Tribal chairman Michael Baines closed the meeting by thanking the officers, and everyone who shared their stories, but he also suggested that the conversation isn’t over. Baines said that if there was anyone in Sitka who has experienced a civil rights violation, the Tribe wanted to know about it.

Robert Woolsey is the news director at KCAW in Sitka.