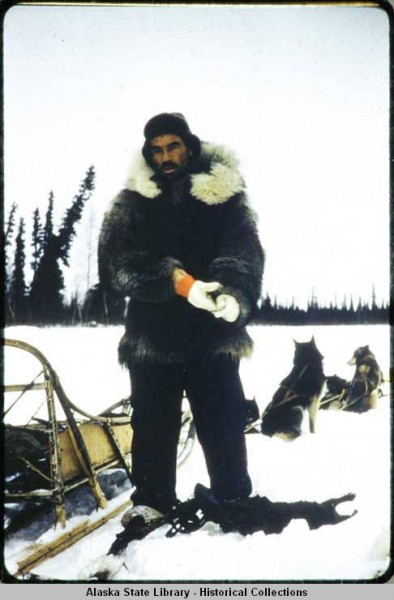

Interior elder Sidney C. Huntington died on Tuesday in Galena. He was 100 years old. He leaves behind not only a long list of accomplishments, but an entire philosophy of life.

Sidney’s biography could go on for hours. His story is so intertwined with the story of Alaska over the past 100 years.

His dad came to the territory of Alaska in the Klondike gold rush. He watched the villages of the middle Yukon and lower Koyukuk valleys transition from isolated, subsistence-based settlements to communities with satellite dishes, snowmachines, and multimillion dollar schools.

But like the villages themselves, Huntington never abandoned subsistence. As he explained in a 1996 interview for the oral history series “Raven’s Story,” Sidney took pride in living close to the land, even after his trapping days were over.

“The change in life has been dramatic. For me to say that I have changed very much…I imagine I have, to quite a degree to keep up with the times. But my variety of food, and what I do, has not changed very dramatically, only I have adapted myself to the new methods of harvesting wildlife resources. And I have a deep respect – probably a deeper respect for wildlife resources than anybody in the country.”

Never lacking in confidence, Sidney did many different kinds of work during his life: hunting, fishing, trapping, boat building, carpentry, mining, fish processing. He served on the Board of Game for 17 years and helped create predator control programs and controlled-use areas to protect moose populations in the Interior. He had a huge family.

He leaves a legacy in Galena not only in terms of what he did, but how he did it.

Sidney insisted on the value of hard work and despised government handouts. He was legendary for starting his work early in the morning, working late into the night, and doing it all again the next day.

Though he only had a third-grade education, he was a strong supporter for public education in rural Alaska. Someone else in his position might say, “You don’t need to go to school. I only went through third grade and look at me now.”

He took the opposite approach. He wanted rural kids to have the formal education that he never had. He loved meeting students at Galena’s boarding school, and considered himself a father to all of them. The Galena K-12 school is already named after him, and has been for 10 years.

But what I think is the most interesting legacy that Sidney Huntington leaves behind is the new Alaska identity that he forged. He was half Alaska Native, half white, and didn’t consider himself a full member of either of those camps. He drew lessons from books, boarding schools and native elders alike to build a lifestyle based on practicality, preparation, and respect.

Each of those values is on display in this outtake from “Raven’s Story,” in which he describes his wolf trapping techniques.

“I wouldn’t tell anybody how I trap wolves. That is not the historic way of doing it. They say you give your luck away and you can’t catch them anymore. Well, I’m about over the hill anyways so it doesn’t make much difference. I generally trap on glare ice, and wolf trapping I’ve found is a lot of work, a lot of work. Dedicated work. You are trapping a very cautious, wary animal. The only thing that gets him – he’s like you and I. He wants to know what is on the other side of the fence.”

Clever, iconoclastic, and ultimately — practical. That was Sidney Huntington.

And of course, Sidney left us his book – “Shadows on the Koyukuk.” It’s become more a reference book than a biography at my house, and I try to reread every year. It never ceases to be a fascinating look back at how Alaska used to be, but also an inspiration to the challenges that lie ahead of us.

I never managed to have Sidney autograph it. But we have a table he built in our cabin, and that seems good enough.