As the ice goes out in the Arctic, many people predict more ships will be drawn through the Bering Straits to take advantage of a shortcut between Asia and Europe. But, a recent government report suggests less ice may not mean more ships.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski has made it her mission to remind Washington the Arctic is opening up. In speeches and at hearings with top officials, she aims to instill a sense of urgency about preparing for an increase in ship traffic and new economic opportunities.

“The time to development the infrastructure and support capacity to handle this growing amount of traffic is now. Actually, it was yesterday,” Murkowski said on the Senate floor last month.

A recent report from the Government Accountability Office runs counter to her message. The report authors interviewed dozens of stakeholders, including executives at cargo companies, mining companies and cruise lines about their plans to send more ships into the Arctic.

“We came to the conclusion that it was going to be limited,” Lorelei St. James, team leader on the GAO report, said.

Two big caveats: The GAO report looked only at commercial activity in the American Arctic,

and only over the next decade, but St. James found that just because ships can traverse the Arctic for part of the year doesn’t mean they will.

“There’s just some fundamental geographic reasons that make it more difficult to operate in the U.S. Arctic,” St. James said.

While an over-the-top route can be 40 percent shorter than the traditional voyage between Asia and Europe, the GAO found container shipping companies aren’t interested. To them, speed is less important than reliability. The business is largely driven by the need for components to move steadily around the globe, from factories to assembly plants to markets. Nobody wants

inventory to pile up, so if ships are late, St. James says, a factory might have to halt production.

“They’re very concerned about on-time, and with the unpredictability of some of the weather patterns up there, it just made the shipping companies we talked to less, the U.S. Arctic less attractive to them,” St. James said.

Time is also a big factor for cruise lines in the Arctic, the GAO learned.

“We were told that even if there were deep water ports or ports that the cruises could stop at, that it just takes so long to go through the U.S. Arctic that there’s just a lack of demand from the mainstream for that type of cruise,” St. James said.

While the Arctic lacks deepwater ports and the U.S. has only two working ice breakers, better maritime infrastructure would not really boost shipping or tourism, St. James says, although miners told the GAO they could use a new dock.

“Right now the zinc that the Red Dog Mine has is lighter than copper, so the copper industry would need a deeper water port but officials told us that they were not prepared to pay for that type of … infrastructure,” St. James said.

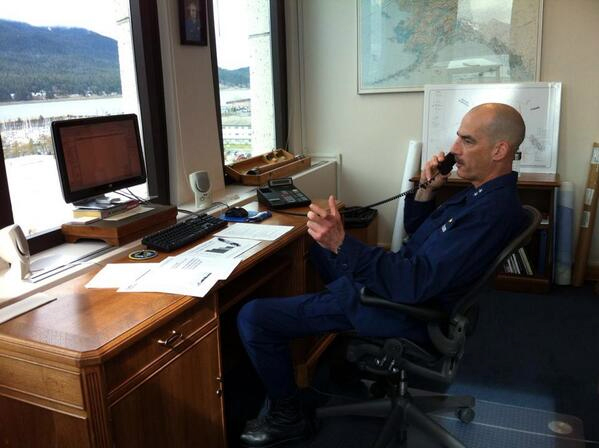

Admiral Thomas Ostebo, commander of the Coast Guard in Alaska, says he agrees with the GAO report and the cautionary note it strikes on building maritime infrastructure.

“Based on what we know now … it’s too early to tell, what infrastructure we need where we would need it and how big it should be,” Ostebo said.

Get those answers wrong and you waste a lot of money. Ostebo says the perceived need for more icebreakers goes up and down, but the Coast Guard is in the very early stages of possibly acquiring a new one. Meanwhile, though, Ostebo says the clearest need in Arctic waters is for things like better maps and charts, improved communication technology and new

environmental surveys.

“There is a future for the Arctic, and those things would be great investments in whatever future comes up,” Ostebo said.

Sen. Murkowski says she appreciates the GAO report’s emphasis on the need for mapping and charting, but maintains Arctic activity is on the rise, so now is the time to invest there.

Liz Ruskin is the Washington, D.C., correspondent at Alaska Public Media. Reach her at lruskin@alaskapublic.org. Read more about Liz here.