A high school diploma is supposed to be a sign of readiness for the next step, whether that’s getting a job or going to college. But in Alaska, it turns out that most of the high school graduates who enter the state university system aren’t ready for the work. Not only are the latest remediation numbers getting attention from lawmakers seeking education reform — they’re already shaping state policy. APRN’s Alexandra Gutierrez reports.

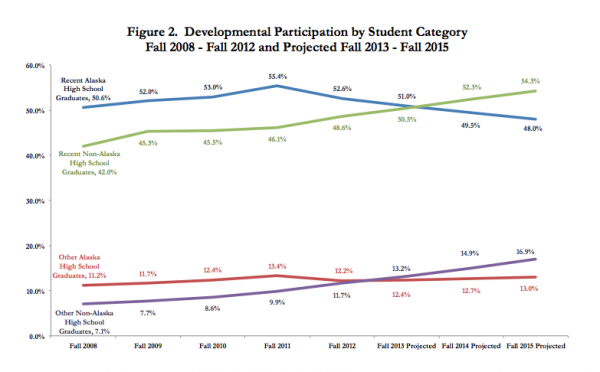

If you’re a recent high school graduate attending the University of Alaska, odds are you’re in the limbo known as “developmental education.” Last fall, a full 52 percent of students were placed in classes that don’t count toward their degrees and are simply meant to catch them up and cover material they should have mastered by the end of 12th grade. If these students were already prepared for undergraduate work, they would be in a much better spot.

“They’re going to typically take at least a year longer to complete their program, so the cost of their education is higher,” says Dana Thomas, the University of Alaska’s vice president of academic affairs. Thomas recently did an analysis of the cost of developmental education.

The financial burden isn’t really on the university. About $2 million is spent getting those kids up to speed, and that’s pretty much covered by tuition. Thomas says it’s mostly hurting the students. On top of paying for extra coursework, they’re losing a year’s salary by not being in the workforce.

“Between those two costs, that’s a substantial amount of money.”

Drilling down into the numbers from the past five years, Thomas found that students who were coming into the university system with their GEDs were the least prepared, with 60 percent of them needing some sort of developmental coursework. On the opposite end were privately home-schooled students. About a third of them had to do remedial work, but Thomas says that percentage is highly variable and based on only a small number of enrolled students.

In the middle were public and private school kids. Fifty-two percent of public school students take developmental education courses, while 47 percent of private school students do.

“[Private schools] do a bit better. Some of that is simply size of operation, I’m sure, and individual personal contact teacher-to-student.”

Sen. Mike Dunleavy has been holding hearings on the cost of education, and he requested the breakdown of which students needed remediation most. He says the public school numbers don’t surprise him, but they’re higher than he’d like.

“If you look at the rates — again, coming from the University and the Department of Education itself — and feedback from businesses and blue collar entities, we still have a ways to go.”

Dunleavy is the former president of the Matanuska Susitna School Board, and he worked as a school superintendent before being elected to the state Senate last year. All the legislation he’s sponsored concerns education, with the most significant item being a constitutional amendment that would allow public money to go to private schools in the form of tax credits or vouchers.

Dunleavy says that while he expects the debate over his amendment to continue next legislative session, he doesn’t anticipate the remediation rates being used in that discussion — even though it’s some of the only hard data that compares public school and private school outcomes in the state.

“There’s both a merit in looking at the numbers in that manner, but there’s also a little bit of a danger.”

Dunleavy adds that he doesn’t think the numbers give a perfect comparison of public schools to private schools. They don’t tell us anything about the students who go out of state for college, or the more than half of Alaska graduates who put off college until later in life or don’t go at all.

On top of that, the public and private school numbers might be dealing with pretty different student populations.

“In the 52 percent that need remediation coming out of the K-12 public schools, we may be including figures that have folks that have special needs. We don’t know if that’s the case with the private schools or the home schools.”

Whether or not the remediation rates factor into lawmakers’ decisions over education funding next session, the numbers are already having an impact on the University of Alaska and the state Department of Education. Officials from both have been in talks about how new state education standards can be tailored to bring those numbers down. The Department has also recently moved to make college preparedness a larger part of its mission.

agutierrez (at) alaskapublic (dot) org | 907.209.1799 | About Alexandra