The dinosaur hunters are back from this year’s field season in Denali National Park. Composed of researchers from Fairbanks, Japan, Korea and Texas, the team was helicoptered into wilderness in the Riley Creek area to look for footprints laid down 70 million years ago.

It’s been about 30 years since University of Alaska Fairbanks professor Roland Gangloff took a serious look at some tracks found during oil exploration on the North Slope and realized they were made by dinosaurs. Then in 2005, they began finding dinosaur tracks in Denali.

Now retired, Professor Gangloff published his book “Dinosaurs Under the Aurora” last year, describing Polar Dinosaurs – creatures that walked the north near the end of the Cretaceous Age, when temperatures above the arctic circle were about like the northern border of the Lower 48.

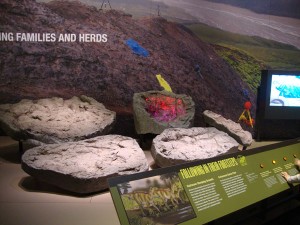

Also last year, the Perot Museum in Dallas assembled an exhibit hall that includes footprints, the assembled skeletons of three Alaska dinosaurs, and begins to tell their story.

Museum curator Anthony Fiorillo has been filling that story out with yearly trips to Alaska for the last 15 years, and they just keep finding more footprints:

“We do answer some questions, but then we raise so many more, and out of the work we did in Denali this year we have made some new discoveries of some animals we haven’t recognized here in Denali before, and it actually was stunning to us because in some cases those discoveries were places we have tromped year after year,” Fiorillo said.

You might not see footprints as exactly dinosaurs’ most exciting features, but you might not be Tony Fiorillo. He can tell from a footprint whether a dinosaur is a meat eater or a vegetarian, and even if it’s a meat eater that switched.

“As a paleontologist you study a lot of anatomy,” Fiorillo said. “And if you know the anatomy of feet – you know, of the skeleton – then you could reasonably interpret um a footprint.”

There are so many footprints now being found, that it’s proving there were an awful lot of dinosaurs in the north.

“We’re demonstrating that dinosaurs didn’t just live in the high latitudes some 70 million years ago, they were thriving back then,” Fiorillo said. “There were big populations of big herbivores, and lots of biodiversity and just some really interesting ecosystem dynamics here.”

There were duck-billed dinosaurs, bipedal dinosaurs, dinosaurs with feathers and dinosaurs that were brightly colored. If you’re thinking that seems an awful lot like birds, you’re thinking like Fiorillo.

“Most of us consider birds to be dinosaurs, and just like birds today communicate with color, we presume that dinosaurs did the same,” he said.

So it’s a whole Cretaceous ecosystem they are puzzling out here. It is near the very end of the time of the dinosaurs, and there are large and small ones, a dinosaur food chain and large abundances of dinosaurs, and their descendants, the birds.

“Denali’s got the best record for fossil footprints of birds anywhere on the planet,” Fiorillo said.

Birds had been evolving from dinosaurs for tens of millions of years by the time of the Denali fossils.

Fiorillo says he’s been studying them so long, and they are so abundant, that he’s beginning to develop a sense for their ancient habitats, 70 million years back in deep time.

“Just like you don’t see animals spread out in one uniform layer across the landscape today – you know, they’re broken out into separate habitats – we think we’re starting to see that with some of these dinosaur remains, some of these footprints,” Fiorillo said. “They’re telling us, there’s patterns that are repeatable enough that we’re confident to make a prediction that when we see a certain type of rock out on the other side of the valley, that if we go over there, we’ll find dinosaur X Y or Z, and we’re starting to have that level of prediction, and so that’s been pretty fun.”

Lugging mould making equipment, GPSs, measuring and image processing equipment up steep slopes that may or may not contain dinosaur tracks might not be everyone’s definition of fun. But now, with the field work over with, comes the interpretation part.

Fiorillo says he returns from every trip with orders to make some changes in the exhibitions. It’s not just the feathers, the colors and the diversity; it’s now subtler and deeper questions about habitat use and how intelligent these creatures were. The dinosaur hunt will go on, and he likes it that way.

“So long as I can remember there were two things I ever wanted to do in life,” Fiorillo said. “One was dig up dinosaurs and the other was play center field for the New York Yankees, so much to the detriment of my parents’ retirement plans, I chose to do what I do, so, yes, I think I’ve been wanting to do this forever.”

The Park Service considers the fossil tracks to be archaeological resources, and locations are closely documented. Public access in the future is not out of the question

sheimel (at) alaskapublic (dot) org | 907.550.8454 | About Steve