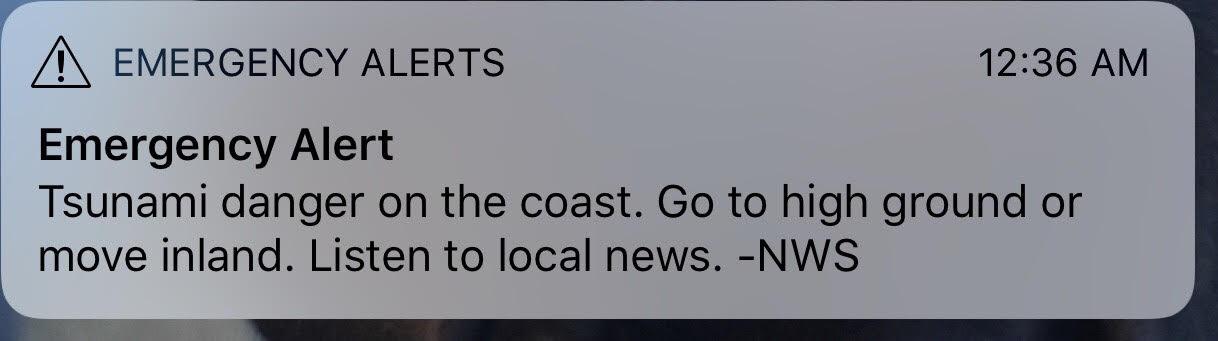

When a powerful 7.9 magnitude earthquake in the Gulf of Alaska hit early Tuesday morning, it sent a host of people and systems into motion. Tsunami sirens were blaring and Emergency Alert System, or EAS, messages were broadcasting over radio and TV stations. But there were parts of the EAS that failed. Local, state and federal officials are now working to sort out those kinks.

When the National Tsunami Warning Center in Palmer decided to issue Tuesday’s tsunami warning, it had to get that message out to the public as fast as possible. The National Weather Service operates the center and it passed the warning on through three primary systems.

National Weather Service offices around the state broadcast the warning over weather radios. Those radios can activate EAS messages at radio and TV stations, but they also set off tsunami sirens and alert those listening to them.

The warning is also sent out through two internet-based systems. The first is called EMnet, which stands for Emergency Management Network. The state contracts out for that service. The other, known as IPAWS or the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System, is run by the federal government.

Both of these services are constantly listening for a signal from the Tsunami Warning Center.

“The FEMA IPAWS system listens to that. Comlabs, who runs EMnet, listens to that feed as well, and it appears that there is a programming error in that link,” Bryan Fisher, Chief of Operations at the State Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, said. “So, it said specifically, ‘do not send it across EAS.’”

Fisher explains that EMnet and IPAWS were supposed to pick up Tuesday’s tsunami warning and send it across the Emergency Alert System.

The systems also listen to each other incase one gets the initial signal and the other doesn’t, but since both were told not to send the message across the EAS, that message stopped there.

However, IPAWS didn’t completely fail. It’s is also responsible for push notifications to cell phones.

“So, it said send it over the cell phone piece, which did work, the wireless emergency alert system, and it blocked it from going to EMnet and EAS,” Fisher said.

The state and boroughs also have the ability to send a signal to EAS equipment, but when warnings are in the National Weather Service’s purview, both typically refrain from doing so.

That left one more method to initiate most EAS equipment, weather radios. When the tsunami warning was issued, National Weather Service offices in Juneau, Kodiak and Anchorage took that message and broadcast it over those radios, triggering EAS equipment across Southeast Alaska and in Kodiak.

But there were some hiccups on the Kenai Peninsula. The National Weather Service in Anchorage said it transmitted four messages to weather radios, but only one made it.

“So, what we’re investigating now is what happened to the second, third and fourth messages that the National Weather Service sent out over NOAA weather radio,” Dennis Bookey said, co-chair of the Alaska State Emergency Communications Committee.

Bookey is one of many people trying to sort things out.

“We’re pretty certain that the audio message, should you have been listening to NOAA weather radio, you’d of heard the whole thing,” Bookey explained. “But there’s electronic coding that gets inside that message that then triggers receivers at the broadcasting and cable facilities. That apparently didn’t trigger them.”

GCI in Homer successfully picked up and broadcast the lone message, but at KBBI, the signal wasn’t clear enough for its system to decode, something the station is working to fix.

KBBI’s system can also be triggered by IPAWS and KSRM in Kenai, but KSRM General Manager Matt Wilson said it received nothing from the National Weather Service in Anchorage.

Officials at every level of government are working to dissect the problem, and Alaska Senator Dan Sullivan expressed concern at a U.S. Senate Commerce Committee meeting Thursday, which happened to be holding a hearing on Emergency Alert Systems.

“Fortunately there was no tsunami, but it was very scary for hundreds if not thousands of my constituents. It would be good to learn from this so we can be ready next time,” Sullivan said.

Bookey said an event with no actual threat like Tuesday’s tsunami warning will be a great lesson because it’s the best test the system could ever have.

“We try our best to do that every March with our annual test, but because of regulations and a lot of variables at play, there’s only so far we can go,” Bookey said. “So, nothing could be more valuable than having a real event and dissect what did and didn’t work.”

Bookey adds that once the issues are diagnosed, changes will likely be made to the system.