Look to the farthest end of the Aleutian chain, so far west that it’s actually east, and you’ll find the Komandorski Islands of Russia.

In 1867, the Alaska Purchase separated them from the rest of the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands. But today, people across the archipelago are still connected by a common history.

A recent cultural exchange helped to renew those ties, bringing Russians and Alaskans together on St. Paul Island.

The potluck is packed and the mood is lively, but the chatter fades as four Russian visitors start to sing. With help from a translator, they explain that this is an Aleutsky song, sung in the Russian dialect of the region’s Native language.

TRANSLATOR: “It talks about how important it is to dance and to listen to music, and I think that’s really appropriate for today. We have all these Unangan people who are together after a lot of years of separation.”

Even though the Komandorski Islands are only a few hundred miles from the Alaska side of the chain, it takes a lot of time, money and effort to bridge that gap across the Bering Sea.

PETROV: “We started out in Nikolskoye and flew to Petropavlovsk …”

Aleksander Petrov is one of the Russian visitors. He’s 15 years old, and he goes by Sasha. He said it took three weeks for his group to make the trip. They traveled through the Russian Far East to Seoul, South Korea, before landing stateside and hopping from Seattle to Anchorage to St. Paul.

PETROV: “At least I got to see the insides of a lot of airports and the electric trains they have in each one!”

Now that he’s finally here, Sasha joked that he’s disappointed because St. Paul looks just like home. It’s foggy and windswept, green and beautiful. Sure, most people live in their own houses, as opposed to the Soviet-era apartments that Sasha’s used to. But for the most part, his life isn’t very different from a kid in the Pribilofs.

PETROV: “I like to walk around and go ride my motorbike and collect mushrooms …”

The similarities do nothing to diminish the significance of the exchange. On the contrary, Aquilina Lestenkof says the islands’ connection is everything.

LESTENKOF: “This is an historic event. I put today in the timeline I maintain for St. Paul history.”

Lestenkof is a teacher and tribal leader in St. Paul. At the potluck, she takes locals and their Russian visitors back to the beginning of that timeline, when their homes were still uninhabited.

LESTENKOF: “In the early 1800s, Unangax were placed on both islands. Both sets. Komandorski Ostrova and Pribylov Ostrova.”

Lestenkof says Russian fur traders moved the Unangax to feed a system of forced labor. A system the American government would later continue. People from Attu and Atka were sent to the Komandorskis to hunt the northern fur seal, while those from Unalaska and other islands did the same in the Pribilofs.

LESTENKOF: “It began a loss of Unangan culture [and] Aleutsky culture. Same time over there and here.”

The long history of oppression has left a lasting mark on all Unangan people, but Lestenkof says it’s part of their shared strength as well.

LESTENKOF: “Who here is of the Bourdukofsky or Lestenkof family lineage? How did you get your last names? Russia!”

PETROV (in Russian pronunciation): “Russia!”

LESTENKOF (in Russian pronunciation): “Russia!”

Beyond celebrating their heritage, the people of the Komandorskis and the Pribilofs are using this time to discuss a common challenge: the changing environment.

FOMINA: “The climate is similar.”

Natalya Sergeevna Fomina is the leader of the Russian group. She works in ecotourism and environmental education on Bering Island.

FOMINA: “The most interesting place is the fur seal rookery.”

Fomina says her community is seeing fewer and fewer seals, just like in St. Paul. They’re also noticing changes to their salmon streams, seabird populations and snowfall. That’s why she was so determined to make this trip a reality. She says it’s important to show young people like Sasha what’s at stake across the region.

FOMINA: “[I] want to inspire them to protect their nature, and the only way to do that is to get them to see it.”

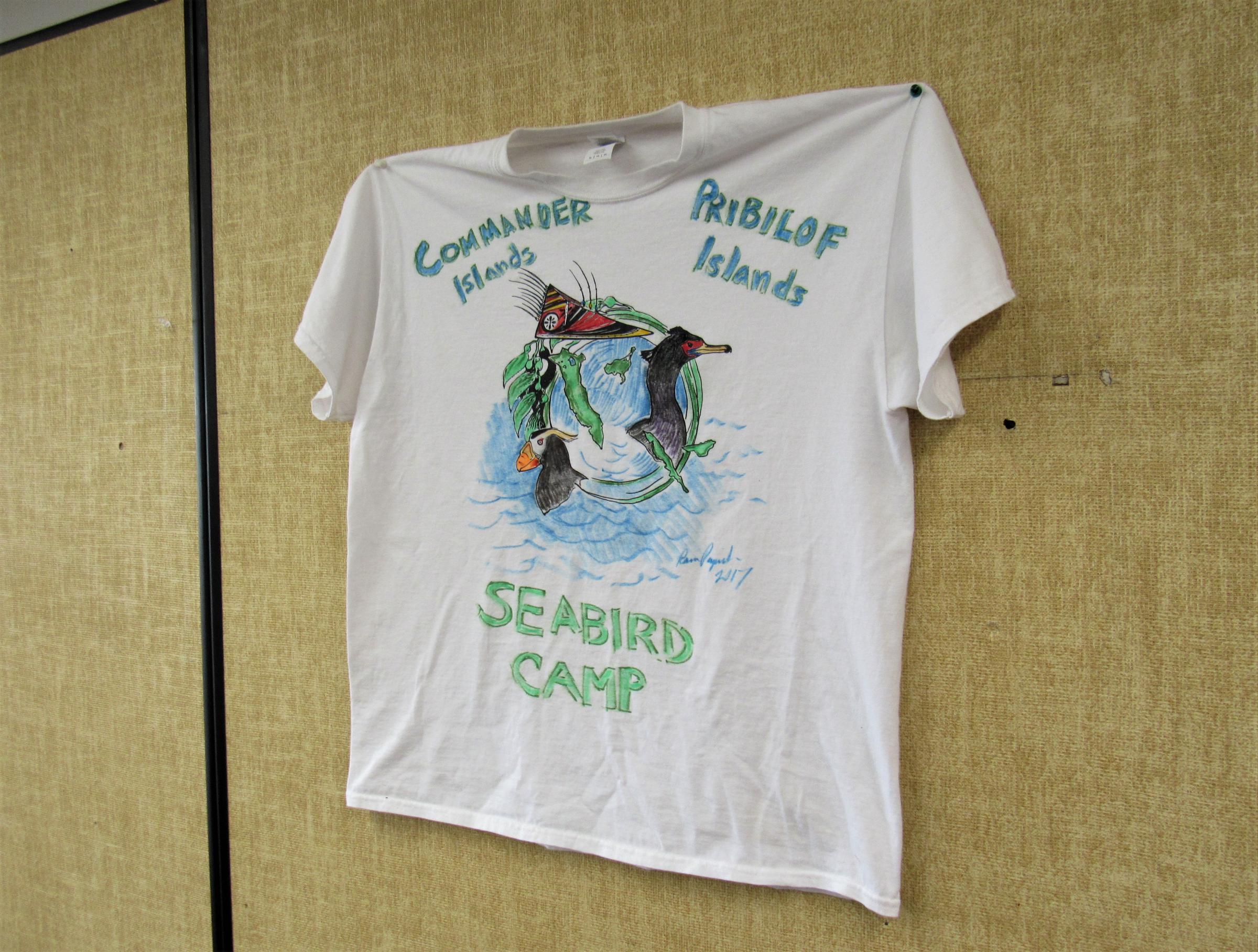

Thanks to the exchange, which was organized by the Seabird Youth Network and National Parks Service, Fomina says she’s collaborating with Alaska educators on a seabird curriculum.

It’ll be taught in the school on Bering Island and in the Pribilof Island School District, educating students about species they share across the archipelago.

TRANSLATOR: “Do you guys remember his name?”

STUDENTS: “Sasha!”

Towards the end of the exchange, Sasha gives a short preview to the students of St. Paul. He teaches them the Russian word for “seagull,” a bird they all know very well.

PETROV: “Chaika.”

STUDENTS: “Ch … ?”

PETROV: “Chaika.”

TRANSLATOR: “Say it again! Chaika!”

STUDENTS: “Chaika!”

Laura Kraegel covers Unalaska and the Aleutian Islands for KUCB . Originally from Chicago, she first came to Alaska to work at KNOM, reporting on Nome and the Bering Strait Region. (laura@kucb.org / 907.581.6700)