Citing tough economic times, Alaska lawmakers and the governor slashed funding for several huge, controversial projects this year, including the Knik Arm bridge and the Juneau Access road.

But Gov. Bill Walker’s administration is now envisioning something new. This year’s capital budget includes $7.3 million in funding to plan the construction of a vast network of roads across the Arctic.

It’s being sold as a lifeline for both oil development and remote communities, but it’s already facing criticism.

There’s no denying that if the Arctic Strategic Transportation and Resource Project, or ASTAR, comes to fruition, it would be a massive undertaking.

“It’s a big project — it’s a megaproject,” Dean Westlake said. Westlake represents the North Slope in the legislature.

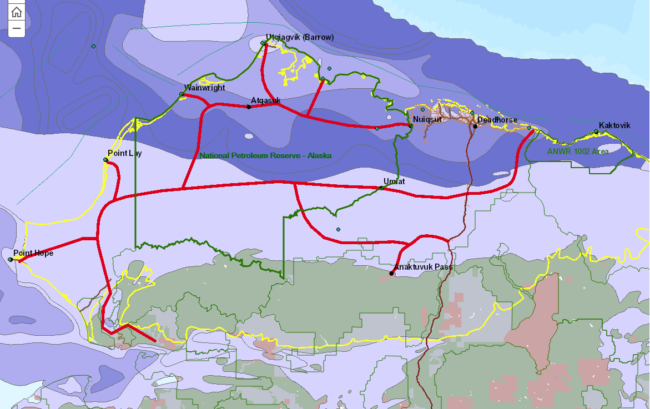

ASTAR would mean a network of roads stretching across the Arctic. If built, you could potentially take a road trip from Nuiqsut, a community near the mouth of the Colville River, to Point Hope, more than 400 miles to the west.

Westlake said the road system would help people in remote North Slope villages where, most of the time, the only way to get from one place to another is to buy a plane ticket.

“It is expensive, a lot of times prohibitively so,” Westlake said. “You have people who want to go to the clinic out there, to the hub, that can’t afford to. And shipping goods to the village — if you lived in rural Alaska, you’d know what I’m talking about.”

The idea also has support from North Slope Borough Mayor Harry Brower; in May, Brower wrote a letter to the legislature in support of the project.

But connecting isolated Arctic communities isn’t the only thing Alaska’s leaders have in mind. On Alaska Public Media’s Talk of Alaska program last month, this is how Gov. Walker responded to a question about why this year’s capital budget included a late addition of $7.3 million for ASTAR:

“We aren’t going to find another 1.6 million barrels of throughput without drilling more wells and having more access,” Walker said.

Walker argued that a network of permanent roads would make finding and developing oil fields in the Arctic a lot easier. The ASTAR project would crisscross one of Alaska’s most promising oil development regions — the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska. One road could lead straight to Smith Bay, where oil company Caelus claims it’s discovered 2 billion barrels of recoverable oil.

The state is hoping the project will hit a sweet spot: it will benefit communities and someday lead to more oil in the pipeline. Andy Mack, who heads Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources, argues that’s why this megaproject makes sense when others don’t.

“Frankly it’s where we have oil plays, and there’s a lot of excitement…and those things are very, very important as we look at our future budgets,” Mack said.

The state also wants to get the project moving during today’s favorable political climate — the industry-friendly Trump administration is now reviewing its management plan for the National Petroleum Reserve. Mack hopes Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke will be open to the idea of permanent roads across the Arctic.

“When Secretary Zinke visited Alaska, he came with a very open mind about what the possibilities were for development in the Arctic,” Mack said.

But there are some big questions that still need to be answered. First, how much will it cost, and who will pay for it? In a letter to the Trump administration asking for support for infrastructure projects this spring, Walker suggested the road from Nuiqsut to Utqiaġvik alone could cost more than $300 million. In addition to federal money, another idea to help pay for the project is to charge industry a toll to use the road.

Some key stakeholders are still trying to figure out what the project might mean to them. That includes ConocoPhillips, which is doing a lot of the oil exploration in the region.

“It is too early in the process to understand how the proposed road system might affect us,” Natalie Lowman, a spokeswoman for ConocoPhillips, said in an email. “We have not been involved with its development.”

Lois Epstein of the Wilderness Society questions why the state is funneling millions into another megaproject that she thinks is unlikely to be built.

“Why are we spending, as a state, lots of money to study projects that have no viability at all? These megaprojects are already being canceled in the most recent capital budget, and at the same time, the ASTAR project is being added,” Epstein said.

Bernadette Demientieff, who leads the Gwich’in Steering Committee, is also against the project. The Gwich’in Steering Committee has long opposed oil development in the Arctic Refuge because of potential impacts to caribou herds. Dementieff said she’s worried a network of roads across the Arctic would threaten subsistence resources.

“The way we look at is they’re looking to do more development. And for us, this is our homeland, these are our children’s birthright to continue to survive off of these areas,” Demientieff said.

As it’s currently envisioned, the ASTAR project wouldn’t connect to any Gwich’in communities.

Amos AguvlukNashookpuk is office manager for Wainwright, a North Slope community that could get its first road out if ASTAR moves ahead. He said a road would reduce the cost of everyday essentials like food and medication — it would even make it easier for Wainwright’s students to travel to basketball games.

“This will help our residents and I hope that one day, it comes true,” AguvlukNashookpuk said.

The state aims to start consulting with communities on the project this winter.

Elizabeth Harball is a reporter with Alaska's Energy Desk, covering Alaska’s oil and gas industry and environmental policy. She is a contributor to the Energy Desk’s Midnight Oil podcast series. Before moving to Alaska in 2016, Harball worked at E&E News in Washington, D.C., where she covered federal and state climate change policy. Originally from Kalispell, Montana, Harball is a graduate of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.