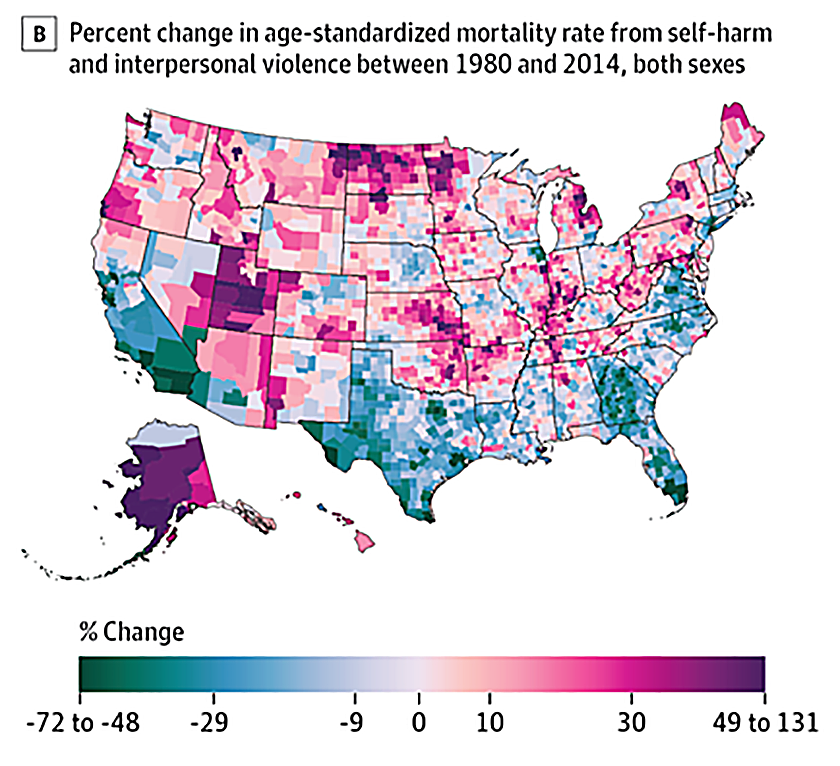

The rate of suicide and homicide in the Kusilvak Census Area, located along the lower Yukon River, more than doubled since 1980, a rate increase higher than anywhere else in the nation.

A study from the University of Washington mapped how people in the U.S. died during those years. Its finding for the area is disturbing. It’s a sobering increase from 51 deaths per 100,000 people in 1980 to 181 per 100,000 by 2014.

The area’s small population numbers were adjusted to be able to compare rates with larger population areas.While the finding from the University of Washington does come with some caveats, Abraham Flaxman, an assistant professor at the University of Washington’s Global Health Department, said it raises a red flag.

“Let me start by saying that 130 percent increase is huge,” Flaxman said. “And anytime we see an increase like that, and it’s an increase in something bad, we want to know about that.”

The data came from death certificates from across the nation, and using this source brings a potential defect to the study.

Flaxman said that even though death certification has been improving since the 1980s, quality varies and coroners in many areas would often list an alternate cause of death to avoid the stigma of suicide.

Another limitation of the study is that it doesn’t show how much of that 130 percent increase is from suicide and how much is from homicide.

But according to the State of Alaska’s death statistics, since 1999, which is about halfway through the study’s timeframe, suicides in the Kusilvak area have far exceeded homicides.

For example, there were 13 suicides and four homicides between 1999 and 2001. Between 2011 and 2013, there were 24 suicides and six homicides.

Presumably suicides account for most of the 130 percent increase, and Flaxman hopes that the numbers help local officials take action.

“So now it is out there, and what happens from there, I really hope this is something people find helpful and can use to improve population health,” Flaxman said.

Suicides in Alaska Natives is no secret.

In this same Census Area in 2015, four people killed themselves in Hooper Bay in a period of weeks.

While the continued high rate of suicides in Native communities took center stage at the Alaska Federation of Natives Meeting that year, one Native man underscored the issue by flinging himself off the balcony and dying in front of the delegates.

One of the people trying to plug the flow of Alaska Native despair is Ray Daw, head of Behavioral Health at the Yukon Kuskokwim Health Corporation.

“Our prevention department, which is about four years old, has done a lot of work at understanding the impact of boarding schools, the impact of the epidemics that occurred two generations ago upon families in the region,” Daw said.

Colonization disrupted the local culture by killing whole families and communities with epidemics and then taking children away from the survivors to educate them in white-run schools. This led to family dysfunction and substance abuse, conditions ripe for suicide because youth lose the capacity to see a viable future.

The YKHC suicide prevention department works to reverse these forces by strengthening the Yupik culture.

It bases its treatment on ways Yupik people lived healthy lives less than a century ago, before there were such high suicide rates.

The department is fully staffed by local Alaskan Natives who all speak Yupik, Daw said.

“Research says that if you’re going to have effective work in behavioral health, you have to have people who are closer to the culture in terms of how they think, feel and behave, and understand the dynamics of problems and solutions a lot more effectively than someone who isn’t,” Daw said.

To get more Alaska Natives providing behavioral health care to Alaska Natives, the department partners with Dr. Diane McEachern at University of Alaska Fairbanks Kuskokwim Campus.

McEachern teaches the rural human services certificate program, and the human services associate degree program. Both are paths to a degree in social work.

Two Yupik elders are always in the classroom with McEachern.

The classes work on how to counsel people and how to heal communities.

McEachern is convinced that these classes can make a real difference.

“So we’re looking at what does it mean for a whole community to experience more health and well-being?” McEachern said. “And if that happens, what are all the ways to help that happen? And then, what outcomes can we imagine from that in terms of the rates of all these issues? Well, they would plummet.”

Professionals are putting their hope in historical healing and resiliency — strengths the elders in the classroom embody, strengths that the students work to build in their communities and strengths that, when they were present, the young did not to take their own lives, but instead grew up and became elders and leaders in their own right.

The classes are rooted in the understanding that the rates of suicide, domestic violence and substance abuse are ways that the fallout from colonization manifest when one culture violates another.

From there, the students can move beyond the past to create a viable future.

“It’s is a social condition that happened to the Yupik people,” McEachern said. “And that’s a powerful insight for people to have, because now they can sit back and go, ‘Oh, it really wasn’t us. So what is us that kept us safe before? And let’s embrace that.’”

But will that be enough to curb a trend that has built and increased over more than 30 years? No one knows the answer to that question.

There have been efforts to bring highly visible discussion of the issue, such as the Pulitzer Prize-winning series “A People in Peril: A Generation of Despair” published in 1988 by the Anchorage Daily News.

There has also been controversy and discussion, both public and private, along with community and private healing sessions. But despite all of this, there is still no sign of a reversal in the trend of increasing suicides in Alaska Native youth.

Johanna Eurich and Steve Heimel contributed reporting to this story.

Anna Rose MacArthur is a reporter at KYUK in Bethel.