The historic Iditarod Trail took center stage during a meeting held by the Army Corps of Engineers Tuesday on the proposed Donlin Gold mine. The route has been changed, but not far enough to suit some longtime mushers.

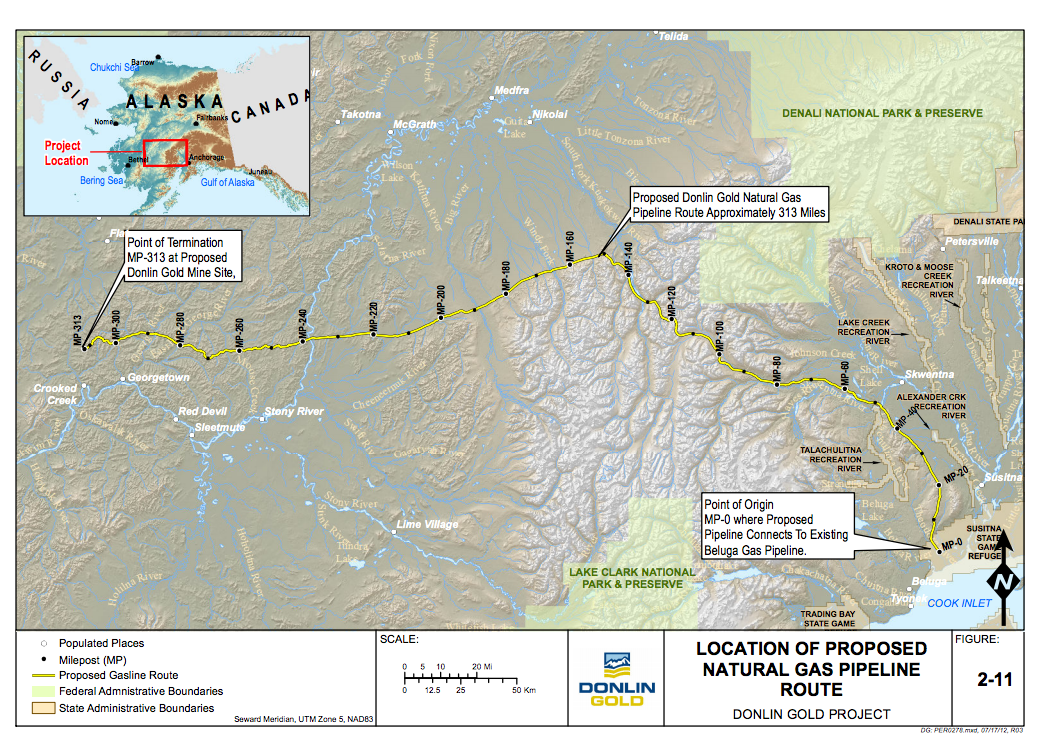

The Iditarod Trail is a National Historic Trail; there is no getting around that. After Donlin Gold’s original proposal for a natural gas pipeline through Rainy Pass raised a storm of objections from some in the dog mushing community, the route of the proposed buried gas line from Cook Inlet now swings north over the Alaska Range through Jones Pass.

This route was used to avoid Rainy Pass, but it does not go far enough, according to Dan Seavey, one of the pioneer mushers who created the last Great Race and worked hard to get the trail its National Historic Trail designation. He notes that the gas line would still follow the trail route from Skwentna to Finger Lake.

“I don’t see any mitigation. I see selecting an alternate to the historic trail,” Seavey said.

Many other mushers weren’t at the meeting, because there is a gag order on those who plan to run the race. Donlin is a major sponsor of the Iditarod.

The Army Corps of Engineers is trying to find ways to mitigate the problem posed by the gas line and other parts of the huge mine project. Sheila Newman, with the Alaska district of the Army Corps, thinks that with enough people at the table, a solution can be found. She hopes that the Seavey family will continue to be involved.

“It was good he was here to talk about what his concerns are and continue the conversation about, you know, what, if anything, can be done to help address some of them,” she said.

Donlin points to community archeological projects like the one recently conducted at Crooked Creek, the nearest village to the mine site, as a method to help mitigate problems. But as far as moving the pipeline right-of-way off the trail route, Enric Fernadez, senior environmental coordinator for Donlin Gold, says the reason it runs along the Iditarod Trail to the Alaska Rage is due to the geography of the region.

“It offers the best geo-technical conditions to place a pipeline, which is coincidentally the reason why the Iditarod Trail is there,” Fernadez said.

There are those who say the company needs to build connections between its proposed gas line and nearby villages. David Gililak Sr. from Akiak says he doesn’t see any reason to build it if it does not improve the infrastructure to the point that affordable natural gas will be available to local residents.

“They shouldn’t actually build a pipeline if it’s not going to benefit Calista region, because we’re the most economically, electrically, socially depressed region in the state,” he said.

Calista Corporation owns the subsurface rights for the proposed mine site. June McAtee, Vice President of Lands and Shareholder Services for Calista, says the Donlin Gold project is not a social service, but it would provide an economic boost to the region, and Donlin’s proposed pipeline would bring affordable natural gas that much closer to the Yukon Kuskokwim Delta.

“The prices of fuel and power and everything else in the region are very high, and there’s no way they’re ever going to come down unless you build something. That’s where we’re coming from, and we think this project has the potential to help us get things built in the region.”

But even if all these issues are resolved, some village residents worry that the pipeline will open remote areas to outside hunters. David Gililak Sr. says the temporary road used to build the gas line won’t stay temporary, even if the company tries to close it, and that would have consequences for Akiak.

“They will be coming in from all over the world. It is a whole lot cheaper to drive than to fly,” Gililak Sr. said. “I mean we’ll have a lot of traffic in that area, eventually to the point where the state will have to call it a road.”

The Army Corps of Engineers plans to hold another meeting on the issue in Bethel by the end of the month or early November.

Johanna Eurich is a contributor for the Alaska Public Radio Network.