The announcement this summer that Alaska will pursue a state-owned natural gas pipeline is a major U-turn after more than a decade of negotiations with the big three North Slope oil companies.

But one person has been advocating this approach all along: Bill Walker.

For years, Walker argued the state should take control of the project, instead of putting its faith in the industry.

Then, he became governor.

This week, Alaska’s Energy Desk is exploring the the state’s 40-year quest for a natural gas pipeline in the series Pipeline Promises.

Today, we look at Gov. Bill Walker’s decades-long mission to build a gas line.

About a year ago, Gov. Bill Walker stood before reporters, addressing his most recent dust-up with the state’s oil companies.

“It has to do with controlling our destiny, and not allowing somebody else to control our destiny,” he said in a Sept. 25, 2015 press conference before lawmakers began a special session on the Alaska LNG project. “I stand firm on that principle.”

This is the heart of the Bill Walker philosophy: this gas line, this “piece of pipe,” as he calls it, is central to Alaska’s destiny, and it is never going to get built unless the state takes charge. We simply cannot leave it to the oil companies, he argued.

Now, Alaska has a chance to test that theory.

For the man in the driver’s seat, the seeds of this philosophy were planted almost fifty years ago, with the state’s other pipeline – the oil pipeline.

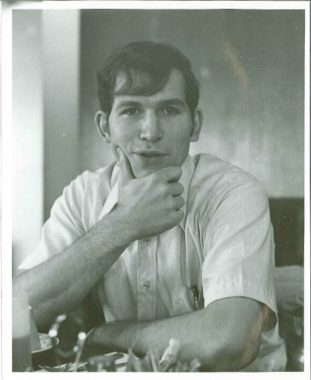

“I graduated from high school in ’69 in Valdez, and I could not afford to go to college,” Walker said in a recent interview. “I mean, there was no way I could afford to go to college.”

What saved him, he said, was early work on the trans-Alaska pipeline. He still remembers getting his dispatch – the piece of paper calling him up for a job on the project.

“I’ve gotten a number of degrees in my life, and I can’t tell you a single name of the person that gave me [them],” he said. “But I can tell you the name of the person who gave me that dispatch. His name was Jim Robinson, it was at the Johnson Trailer Court in Valdez, and I stood there with a couple of my buddies, and I thought, ‘This is my ticket, for my future.’”

Walker says what the last pipeline meant to him, the next line could mean for a whole new generation. Jobs, of course. Revenue for the state. Cheap energy that could launch whole new industries. New incentive for companies to explore the North Slope.

His first encounter with the gas line came a few years after that moment in the Valdez trailer court. Walker was in his mid-20s. He’d just met his wife, and he was serving on the Valdez City Council.

“And the mayor said, ‘who wants to work on the gas line?’” Walker said. “I said, ‘well, I’ll work on the gas line. I worked on the oil line, so I’m happy to work on the gas line.’”

He ended up traveling to California to meet with then- (and now-) Gov. Jerry Brown to advocate for an Alaska LNG line to ship gas to the West Coast. That version of the project, like so many after it, fizzled. But Walker stayed involved in oil and gas — and often found himself at odds with the state’s dominant industry.

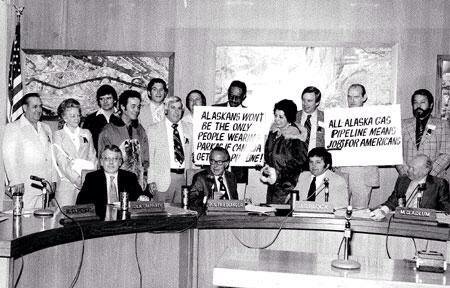

In the late 1990s, the gas line came back into his life. He was called to a meeting of mayors from the North Slope, Fairbanks and Valdez. They had formed a group called “Gasline Now!”

“[They said], what can we do to add a few more percentage of return to the gas line, so the producers would build a gas line?” Walker said.

The idea was to jump-start a project by using the local governments’ tax-exempt status to try to tempt the oil companies to the table. The result was the Alaska Gasline Port Authority (AGPA).

Walker ended up working with the Port Authority for more than a decade, trying to advance what he called an All-Alaska Gasline. (During this time, he also represented the City of Valdez in a long-running court battle with the North Slope producers, arguing the companies had undervalued the trans-Alaska pipeline in order to pay lower property taxes.)

Craig Richards went to work for Walker as a 27-year-old lawyer in the early 2000s. He went on to become Walker’s law partner, confidant and ultimately his first attorney general.

“Bill wasn’t doing academic papers. Bill was doing the real deal, he was meeting with Fortune 500 companies, and having real meetings about ways to monetize the gas. It was just very enticing,” Richards recalled.

He said the Port Authority years taught Walker several things. There were moments when Walker thought he’d pulled it off. He brought in big outside companies, like the California utility Sempra Energy, or Mitsubishi, who were interested in a project.

They’d reach out to the North Slope companies who controlled the gas.

But, Richards said, “Phone never rang. Dead silence.”

“The answer of course, is that producers weren’t interested at that stage in making a pipeline happen,” Richards said. “They were interested in accomplishing other goals.”

This included goals like using gas line negotiations with the state to lock in their oil and gas taxes and a friendly regulatory regime, Richards said.

Critics say the Port Authority never put together enough of a project to merit a real response.

But Richards said for him and Walker, the lessons were clear: The oil companies have their own priorities and their own timeline. If the state wants a gas line, it can’t wait for the companies to lead the way.

“One, he decided that he needed to be governor, if he was going to really see the gas line go to the next phase. And that was the beginning of his political ambitions,” Richards said. “And two, he realized it’s gotta be the state of Alaska that does this. At least in terms of the pre-development work.”

In 2010, Walker ran against then-governor Sean Parnell in the Republican primary, with the gas line as his main issue. In an ad from that era, Walker says: “Folks ask me if I’m a one-issue candidate, and I’ll admit and it’s certainly no secret, I am committed to Alaskans building an all-Alaska gas line…”

He lost that year, but ran again in 2014, as an independent. By then, Parnell and Republican lawmakers were advancing a new plan, a partnership with the big three North Slope producers – ExxonMobil, BP and ConocoPhillips – as well as the pipeline company TransCanada: the Alaska LNG project.

Bill Walker was not a fan.

“The fatal flaw of what he is doing is, again, again, he has put control of Alaska’s future in the hands of companies that have competing projects around the world,” he told KTVA’s Rhonda McBride in an interview in May 2014.

Then, the unexpected happened: Walker won the election.

Former Anchorage Daily News reporter Bill White has researched the history of the gas line. I asked him if Walker’s single-minded pursuit of a state-owned project is his white whale – his Moby Dick.

White: It’s his big obsession, for sure. Remains to be seen if it’s his white whale.

Alaska’s Energy Desk: Why?

White: Well, maybe he’s right. I wouldn’t bet on it, but maybe he’s right.

Now, Walker has a chance to prove it.

When he took office, oil and gas prices were plunging. Suddenly Alaska faced a massive revenue shortfall, and Walker was more convinced than ever that a gas line is the solution.

But low prices also created an opening, changing the dynamics of the Alaska LNG project Walker had inherited from Parnell.

On February 9, 2016, the state’s three oil-company partners sat down with Walker’s team.

“It was a day I’ll never forget,” Walker said.

According to both the governor and ExxonMobil, the companies told him that lousy market conditions and slow negotiations with the state meant they probably couldn’t move the project ahead as planned.

They proposed either slowing down or letting the state take over.

For Walker, this was his moment. And he seized it.

“I thought, my goodness. How long have we waited for this opportunity,” he said. Within months, his administration had announced it would pursue a state-owned project.

For many Alaskans, news that the big three oil companies have stepped back from the project is a sign the state’s gas line dream has hit another wall. But Walker doesn’t see it that way.

“We have proved over the last forty years what won’t work,” he said. “This is the first time we’ve said, let’s try it, one time, like other sovereigns do around the world.”

It’s not a wall, he said. “It’s a starting gate.”

Rachel Waldholz covers energy and the environment for Alaska's Energy Desk, a collaboration between Alaska Public Media, KTOO in Juneau and KUCB in Unalaska. Before coming to Anchorage, she spent two years reporting for Raven Radio in Sitka. Rachel studied documentary production at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, and her short film, A Confused War won several awards. Her work has appeared on Morning Edition, All Things Considered, and Marketplace, among other outlets.

rwaldholz (at) alaskapublic (dot) org | 907.550.8432 | About Rachel