New research reveals salmon played an important role in the diets of ice-age Alaskans. The information comes from an archaeological dig on the Tanana. Two University of Alaska Fairbanks scientists applied new techniques to uncover clues about the lives of Alaska Natives almost 12,000 years ago.

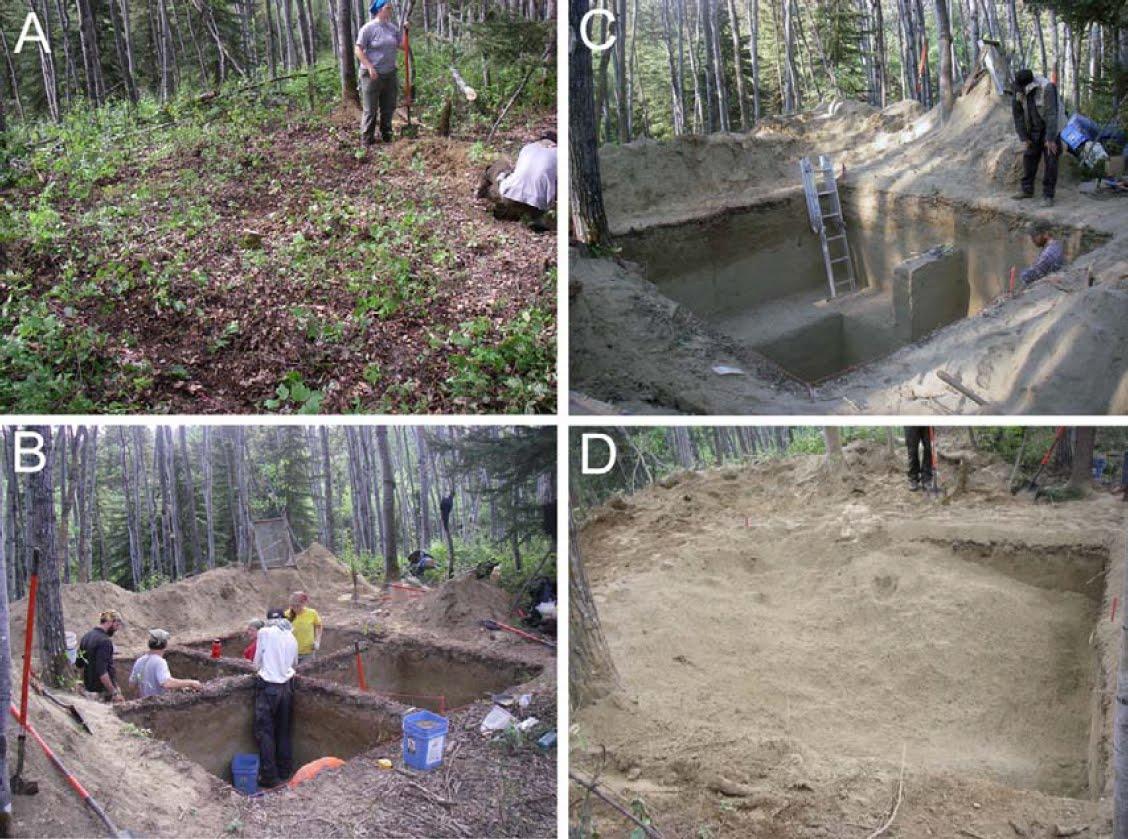

This isn’t the first time new insights into the lives of ice-age Alaskans have come from the Upward Sun River site. Besides cremated human remains, the archaeological dig on the banks of the Tanana River has revealed some 17 cooking hearths of ancient people stretching aback more than 13 thousand years. UAF Anthropology professor Ben Potter is the key researcher of the dig and he says he and his colleagues had previously uncovered salmon bones more than 11 thousand years old.

“We had to get the genetic analyses to identify what species it was, and it was chum salmon,” Potter said. “And so the isotopic analyses to show that they were marine. In other words that they were behaving as chum salmon do today.”

The question, says Potter, was whether those ancient peoples were opportunistically catching salmon, or whether they systematically and repeatedly returned to the site each season to harvest the fish. To answer that he turned to a geochemist working at UAF, Kyungcheol Choy.

Choy drew on a recently discovered technique of analyzing long lasting chemical residue in ancient cooking pots. Unfortunately, there weren’t any pots, only hearths. Nevertheless, by gathering the unique nitrogen and lipids chemical signatures of modern fish and animal species he was able to test samples dating back 11,500 years for the chemical signatures. He said Alaska conditions helped.

“We in Alaska have a very good preservation conditions compared relatively to other areas,” Choy said. “But our study proved that nitrogen is still preserved for a long time.”

Choy says once he got the test results back he and his colleague ran them through statistical models to determine just how much fish figured in ancient diets. Anthropologist Ben Potter said the results open a new window into ancient practices.

“It’s one thing to say you got a salmon, and we could say that before,” Potter said. “Now we could say that there were probably different, multiple groups that are clustered around these different hearths and they were doing the same thing. So that’s different. That suggests that they were here specifically to capture the salmon.”

Moreover, Potter says the data demonstrate the practices extended across hundreds if not thousands of years. Choy and Potter’s research was published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.