Food scientists with the help of a botulism expert are trying to combine science and traditional Alaska Native methods to make one prohibited food safe to eat. Regulated programs under the State of Alaska Food Safety and Sanitation Program are not allowed to accept or distribute seal oil due to the danger of botulism, a potentially fatal disease which is caused by bacteria in contaminated food.

But how or when the neurotoxins enter the rendering process is still a mystery. That’s what researchers want to find out.

Val Kreil describes seal oil as “a little bit like a heavy olive oil.” He’s the administrator of Utuqqanaat Inaat, a long-term care facility in Kotzebue that falls under the Maniilaq Association.

He says elders at the facility identified seal oil as a priority food.

“For them it’s like eating butter. This is just part of their daily diet. This is what they’ve always been eating and, in terms of health, it’s actually healthier than fish oil. So, there’s a lot of benefit to eating seal oil.”

But because the bacteria that causes botulism grows in anaerobic environment – or one without exposure to oxygen – traditional methods using containers like bottles or barrels to render the seal oil can lead to contamination. The challenge is how to prevent the risk of poisoning while working with the traditional techniques.

Kreil says, beginning last year, Maniilaq started looking for ways to get a variance approved to distribute seal oil. He says he’s one of a number of Alaskans interested in getting prohibited traditional foods safe and approved for consumption, and he hopes to clear the way for other programs.

The first step in the mission was to turn to regulators.

Lorinda Lhotka, a section manager with the State of Alaska Food Safety and Sanitation Program, says the state was willing to allow organizations to serve the seal oil if they could demonstrate a safe process.

However, she explains Lorinda Lhotka needed to reach out to resources other than the state.

“We do testing, but it’s usually in result of outbreaks of illness, and we don’t do a lot of preventative testing to help evaluate the safety of the product. So, it’s usually just in response to illnesses, and our labs don’t have that capacity.”

So, along the way, Maniilaq got in touch with UAF’s Kodiak Seafood and Marine Science Center, and Dr. Eric Johnson, a botulism specialist and professor of bacteriology at the University of Wisconsin – Madison.

He has a long history in researching botulism and his lab is registered for toxin analysis.

Johnson says he’ll watch the traditional process in action in the community of Kotzebue and, once he understands the preparation, examine samples in his lab.

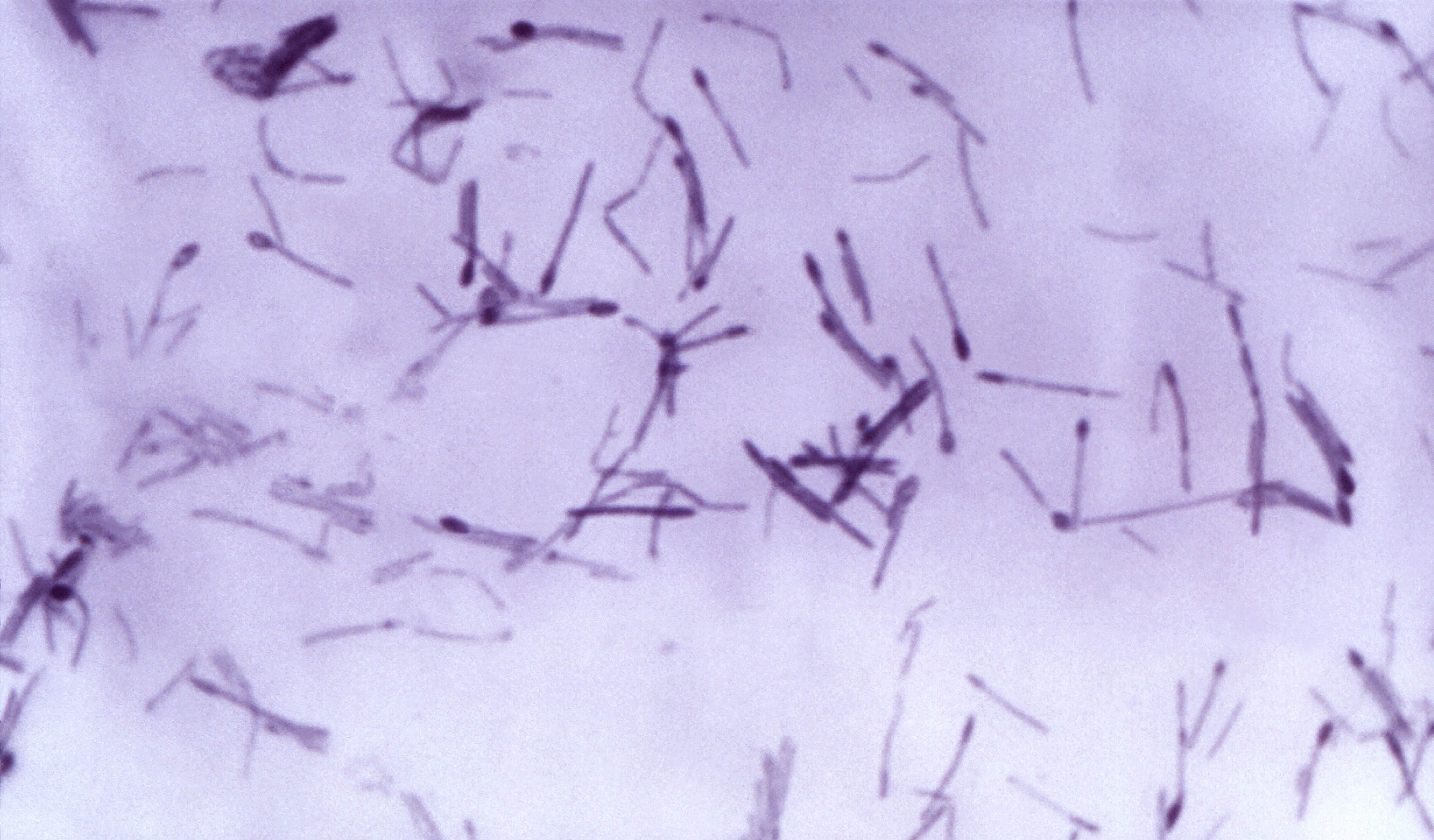

“My interest is in helping validate the process from a safety perspective – for example, what aspects in this process may contribute to the growth of clostridium botulinum and its formation of toxins and to implement minor changes in the process that will enhance its safety.”

While the Seafood and Marine Science Center is not registered to work with toxins, it does focus on the research of seafood. Associate Professor of Seafood Microbiology Brian Himelbloom explains they can study the other aspects of a seal oil sample, like what it’s composed of and how much water is left in the extract.

“Because that will give us an idea when things go bad maybe that’s because some of that seal oil has some residual water available and that’s where we theorize clostridium botulinum is actually going to operate.”

Himelbloom says, in theory, the preparers of the seal oil can avoid a botulism incident if they pour off 100% oil.

“But in their mixing, if there’s splash over from water or they’re not careful how they’re pouring it off, maybe that’s the situation – because under what we call ambient temperatures, room temperature or outside temperature, that’s probably in the range where this organism can proliferate.”

So far, it’s all speculation. The trick according to Himelbloom and the other researchers is to find the solution while keeping scientific intervention to a minimum.

“We know something about clostridium botulinum and how it acts and how it behaves and where it can be found and how you test for it and how do you assay for the toxin, and so if we can combine those two worlds of traditional knowledge and Western science, we might actually come to the point of oh, now we know how we can most likely guarantee, hopefully, that there won’t be a botulism incident if they follow these particular steps.”

Next, researchers will observe the traditional process, and then, through collaboration with each other, Maniilaq, and other community partners in Kotzebue, they’ll decide on what they should test and how much of it.

Johnson will visit Kotzebue today and Friday to watch how local processors render seal oil.

Kayla Deroches is a reporter at KMXT in Kodiak.