It’s being called a marine heat wave. The combination of the strongest El Niño in recent history and the warm water anomaly known as the Blob generated the greatest amount of warm ocean water that has ever been recorded, possibly affecting marine life up and down the West Coast.

New research has now linked the two phenomena, with each believed to be alternately affecting the other through the atmosphere and the ocean.

El Niño is the warming of the equatorial Pacific Ocean and it can affect wind, temperature and precipitation patterns around the globe. While the latest El Niño did bring some needed precipitation to parts of the drought-stricken West Coast, it was also blamed for flooding, mudslides and other damage in California, according to an ABC News story in January.

After peaking in late 2015 with sea surface temperatures of at least 2 degrees Celsius above normal, the latest El Niño has disappeared. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center in Maryland recently reported that sea surface temperatures have dropped to below average in the eastern equatorial Pacific over the last two months.

But while El Niño is dead, the Blob lives on.

“To put it in a little bit more colorful terms, kind of a lingering hangover,” said Nicholas Bond, a research meteorologist at the University of Washington and the state climatologist for Washington.

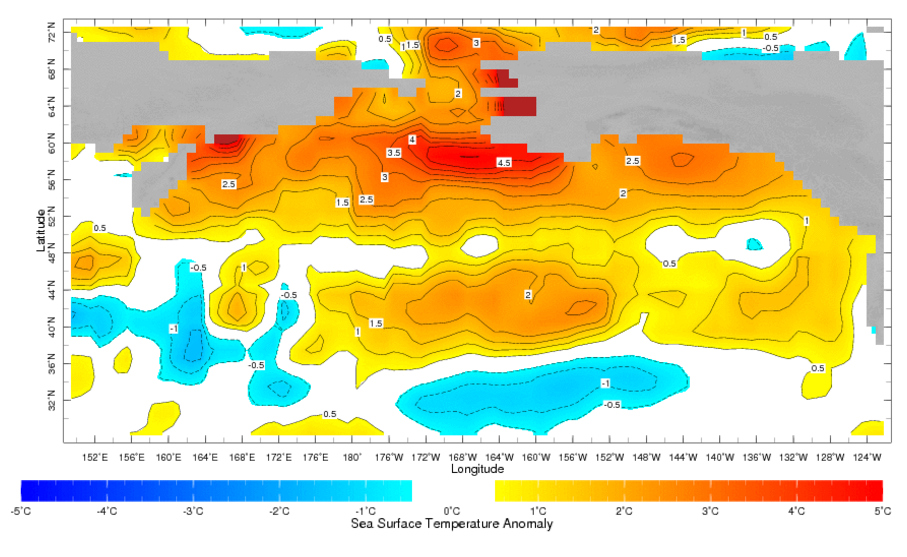

Bond said latest sea surface temperature measurements show that unusually warm conditions are still persisting, especially in the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea.

“For the Gulf of Alaska, 2.5 degrees C warmer than normal and in parts of the Bering Sea it’s 4 degrees C, or 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than normal,” Bond said. “I noticed some temperatures there near the west coast of Alaska that were 16 degrees C. That’s over 60 degrees (Fahrenheit) in the Bering Sea.”

Bond first identified the warm water anomaly three years ago and nicknamed it The Blob. He said unusual weather patterns have allowed the ocean to retain that heat.

“It got quite a bit warmer than normal, quite deep depths, as deep as 300 meters or so,” Bond said. “There was just a tremendous reservoir of this extra heat that is taking a long time to go away.”

That means that Alaskans, especially along the coast, could expect warmer weather this summer.

New research suggests a link between the Blob in the North Pacific and the former El Niño in the tropical Pacific.

“El Niño was kind of in the middle of the event in terms of changing the pattern of ocean warming and making it last for three years,” said Nate Mantua, a climate and fisheries research scientist at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center in Santa Cruz, California.

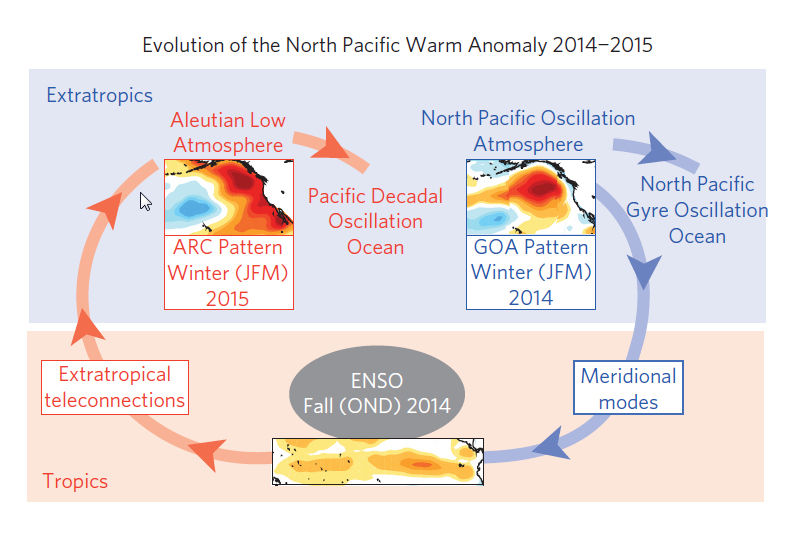

In a paper published in July in the journal Nature Climate Change, Mantua and his co-author, Emanuele Di Lorenzo of the Georgia Institute of Technology, examined the connections between the two separate ocean events despite the great distance between them.

The Blob’s formation in the Western Pacific’s extratropics, or mid-latitudes beyond the tropics, in 2013 could have had a small influence on the development of the weak tropical El Niño of 2014. Then, during the stronger El Niño that developed in 2015, warm temperatures at the equator remotely affected the storm track and weather patterns in the North Pacific extratropics.

“The El Niño influence favors a much stormier weather pattern that includes a lot of wind from the south along the coast of the Pacific Northwest into Alaska,” Mantua said. “That is what caused the offshore warm Blob to move inshore and to expand.”

Mantua calls it a marine heat wave, and he said the amount of warm water was dramatically more than any other event in the historical record dating back to 1880.

The Blob and El Niño tag team is the prime suspect for several unusual biological events along the West Coast in the last three years. They include sea bird die-offs, giant algal blooms, demoic acid in shellfish, whale and marine mammal strandings, and low salmon returns and lightweight salmon.

“This is all indicative of a lot of stress on the marine food web lower productivity that’s in keeping with this idea of what warm water typically does,” Mantua said. “It just reduces the ability to get nutrients up into the sunlit upper ocean and cuts down on the abundance of the lipid-rich, sub-Arctic species that we find at the base of the food web.”

Mantua said there’s no evidence yet that global warming prompted the recent arrival of the Blob. But he and his co-author do believe that such events may happen more often and with greater intensity as the ocean warms.

“We see that the energy in the climate patterns that caused the warm Blob, it increases,” Mantua said. “By the end of this century, the energy increases about 16 percent over that from the late 20th century.”

Short-term relief may just be around the corner. Temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean are cooling, finally signaling an end to one of the strongest El Niños in 20 years. Bond said there’s an increased chance that the pendulum will swing the other way this winter toward La Niña, or equatorial cooling.

“And, if it has the usual sort of atmospheric pressure and wind patterns associated with it, then we should continue to see continued moderation of temperatures in the Northeast Pacific, Gulf of Alaska, Bering Sea, and off the Pacific Northwest Coast,” Bond said.

“And more wind out of the north, more cold storms, and that could start moving the Blob out,” Mantua said.

Mantua notes that current weather patterns are already much different than those that created the Blob. He said we’ll know more in six to nine months.

“So, La Niña would be good for bringing things back to normal, maybe even getting us a little cooler than normal,” Mantua said.

Matt Miller is a reporter at KTOO in Juneau.