Climate researchers say a giant mass of warm water in the Pacific Ocean may be responsible for unusual sightings of marine life in the North Pacific while also influencing North American weather patterns.

Nicholas Bond, a climatologist for Washington state and a research scientist at the University of Washington’s Joint Institute for the Study of Atmosphere and Ocean, came up with the 1950s sci-fi movie inspired nickname The Blob for the huge, evolving mass of warm ocean water.

“I started seeing this very unusually warm water in a semicircular patch about a year ago,” Bond said.

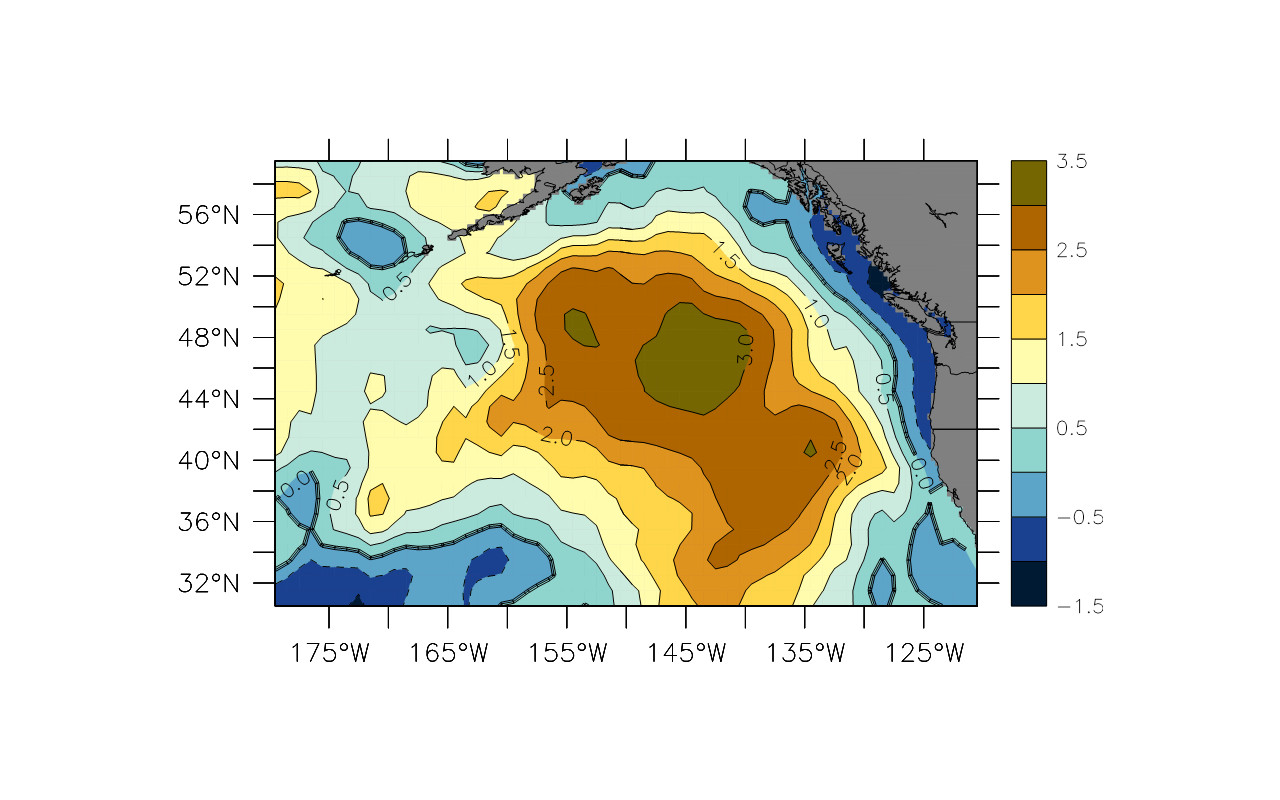

He says down to a depth of a hundred meters temperatures have increased more than two degrees Celsius since the fall of 2013.

“It was a big event,” Bond says, adding that it was the biggest anomaly seen in the last 18 years.

In a paper published last month in the Geophysical Research Letters, Bond and his co-authors say it was caused by a lingering high pressure system that normally inhibits cloud formation and precipitation. The high pressure over the eastern North Pacific blocked the usual parade of winter storms, diverted surface winds and prevented the usual ocean cooling.

“Also, the weird direction of the winds meant that in the region of The Blob there’s more warm water coming up from the south than usual to make it warmer there,” Bond said.

The higher temperatures coincide with unusual bird sightings in the Pacific Northwest and catches of tuna, sunfish and a thresher shark in Alaska.

The Blob wasn’t the sole cause, but Bond says it could’ve helped divert frigid Arctic air to the Great Lakes Region last winter. It also could have contributed to a dry West Coast and mild winters along the Alaska coast, simultaneously bumming out skiers and snowboarders and pleasing municipal managers overseeing street snow removal budgets.

“It makes more sense that — in the short-term development phase — the atmosphere drives the sea surface temperatures in this part of the world,” says Rick Thoman, a climate specialist with the National Weather Service in Fairbanks.

Thoman says they’re seeing those higher temperatures deeper in the ocean, not just at the surface.

“That means that’s not likely to change in the short term, say a few month change,” Thoman says. “That warm water extends through a depth of the ocean and that will take a while to change.”

Bond calls it thermal inertia, and he warns that we may see the effects of The Blob even through next winter.

“So, it’s not due to climate change. But it’s a taste of what we’re going to be getting more of in future decades,” Bond said. “I look at it as an opportunity to learn about what climate change is liable to bring us.”

Six Alaskans are among the scientists and resource managers meeting at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California this week to discuss The Blob.

Over the last two winters, The Blob has moved and stretched out along the western coast from the Gulf of Alaska to Baja California. It’s unclear how it will affect juvenile salmon now heading out to the open ocean and mature salmon returning to Alaska streams this summer.

Matt Miller is a reporter at KTOO in Juneau.