The First Alaskans Institute hosted a Racial Equity Summit in Anchorage this week. The event’s dialogues focused on what racial equity is and how we can start to achieve it.

Racial Equity and racial equality are not the same thing. Equality means everyone is treated the same or given the same resources. It assumes that everyone starts at the same point. Equity means making sure everyone can arrive at the same point, no matter where they start.

Gyasi Ross is a member of the Blackfeet Nation and lives in Washington. He speaks on social justice and race issues and presented at the summit. He says to achieve racial equity, communities first need to acknowledge that underlying systems deny people of color equal starting points.

“We think that now we have this quote-unquote colorblind society — which doesn’t exist but even if it did exist, so what? The foundation wasn’t colorblind. The foundation wasn’t equal. And that creates a structure that’s on an unequal playing field, an asymmetrical playing field from the very start.”

He gives the example of land ownership. Black people in the United States couldn’t own land until the late 1800s. As a result, whites currently own about 850 million acres of agricultural land. Blacks — just 7 million. Ross says to change that basic inequality, people with privilege need to be okay with losing some of their privilege. But that’s not an easy thing to talk about.

“The point is that equity as a serious conversation, and there might be uncomfortable conversations and some level of displacement, and we have to be okay with that,” Ross says.

So how do we get beyond that discomfort? Summit speaker Jay Smooth, who speaks and writes about race and culture, says we need to change how we frame the conversation.

“We tend to frame each conversation as a referendum on whether I am a good or bad person. And if I’m a good person then I don’t need to consider whether I’m prejudice or have any blind spots toward people or whether I’m part of a system that perpetuates injustice even if I’m not consciously contributing to that.”

Smooth says people need to think beyond good versus bad and be actively looking for our own unconscious biases and the ways we perpetuate racist systems.

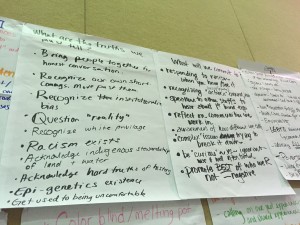

But for some Alaskans, like extension officer Kari van Delden from Nome, that means first identifying why the conversation is so hard to have. She’s white and helps host conversations about race in her community with Panganga Pungowiyi, the director of Kawerak’s Wellness Program.

“For a long time I was really uncomfortable talking about anything around racial issues,” van Delden says. “So I had to start trying to figure out why is this an uncomfortable conversation for me. And there were a lot of things like I would find myself feeling like I needed to defend something or feeling like somebody would misunderstand me. So I had to start understanding why I was backing away from the conversations or avoiding them before I could even start having the conversations.”

Pungowiyi says one of the first steps for talking about race is acknowledging the history of external and internalized oppression.

“True history about Alaska Native people is not taught, and when that history is kept from you and you don’t know how your families and your communities have gotten into the situation that they’re in with all these symptoms of historic trauma manifesting, like alcoholism, like abuse, like violence. All of these things. The high suicide rate. When you don’t realize there’s a reason for all these things, you become internally oppressed. You just feel inferior.”

Pungowiyi says it’s a feeling you have to heal from–it’s part of a community-wide healing process. She tries to incorporate conversations about race into all aspects of life in Nome. Because if people can talk about it, they can make systems more equitable for everyone.

The First Alaskans Institute hosted the two-day conference in Anchorage as part of their ongoing work on racial equity.

Anne Hillman is the healthy communities editor at Alaska Public Media and a host of Hometown, Alaska. Reach her atahillman@alaskapublic.org. Read more about Annehere.