The battered remnants of two whaling ships from the 1800s were discovered in the Chukchi Sea this fall. NOAA archaeologists say they can thank an increasingly ice-free Arctic for the find, saying it’s improved their access to potential shipwreck sites.

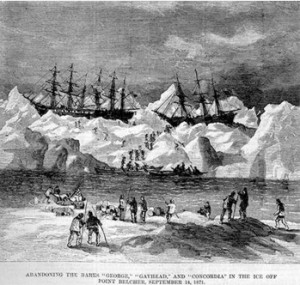

The ships are believed to be from the 1800s — specifically 1871, when 33 ships were trapped by sea ice in an unusual stranding event. The whaling captains had counted on a wind shift from the east to push the ice back out, as was the seasonal norm. But the favorable wind never came.

The ships were destroyed, leaving more than 1,200 whalers stranded. Miraculously, all survived. They were rescued by ships moored farther south in Icy Cape. But the loss of property was a major low for the Yankee whaling industry.

A team of archaeologists from NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program had an inkling a 30-mile stretch of coastline near Wainwright could be fruitful searching grounds for remnants of the 1871 stranding event. Previous searches had found traces of gear salvaged by local people, plus washed-up ship debris on shore.

Brad Barr is a NOAA archaeologist and co-director of this project. “Earlier research by a number of scholars suggested that some of the ships that were crushed and sunk might still be on the seabed.”

The team used modern sonar technology to outline the flattened hulls of the two wrecks. Anchors, fasteners, ballast and brink-lined pots used for rendering whale blubber into oil were also found.

“Until now, no one had found definitive proof of any of the lost fleet beneath the water,” Barr says. “This exploration provides an opportunity to write the last chapter of this important story of American maritime heritage.”

At the time of the stranding in September 1871, the captains of the 33 whaling ships convened to weigh their options for saving the 1,219 officers, crew and even families from an icy fate. The nearby mooring of seven ships 80 miles to the south was a godsend.

But in order to make room for the survivors, the seven ships in Icy Cape had to jettison their cargoes of whale oil, bone and whaling gear. Barr calculates the loss to the New Bedford whaling fleet was over $33 million in 2015 dollars. All seven rescue ships sailed safely out of the Arctic to a myriad of different destinations: Honolulu, San Francisco and New Bedford among them.

Sonar images of the shipwrecks are available through NOAA.