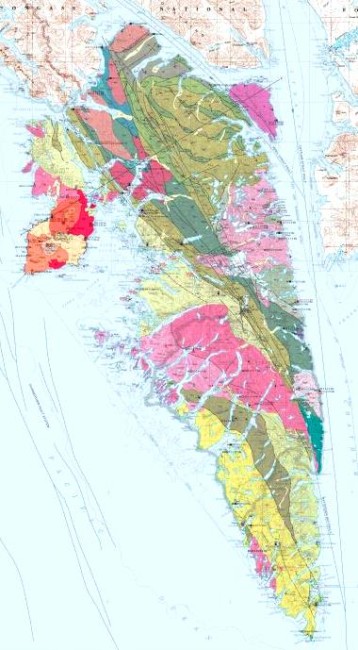

Sitka sits on a different chunk of the Earth’s crust than the rest of Alaska. Decades of scientific research have led to a report and map showing where the faults lie. The new information expands scientists’ understanding of what’s going on beneath Alaska’s surface.

Fly into Sitka on a reasonably clear day and it’s hard to miss its most prominent chunk of rock.

Mount Edgecumbe volcano rises 3,200 feet above sea level. Neighboring cinder cones from separate eruptions are also impressive.

But it’s only one of Baranof Island’s geologic features. Over the past 40 years, researchers have turned up some less-obvious portions of what’s below Southeast Alaska’s landscape.

“We now know that the geology on Baranof Island and West Chichagof Island does not match the rest of Southeast Alaska,” says Susan Karl, a research geologist for the U.S. Geological Survey in Anchorage.

She and other scientists collaborated to research and create the new Baranof map and accompanying reports.

“We also have spent a lot of time trying to figure it out where it came from, why it came, how it came and when it came from wherever it came from before to where it is now,” she says.

Baranof Island, and part of its northern neighbor Chichagof Island, sit atop their own block of the Earth’s crust.

It’s one of many plates and blocks, as they’re called, in motion around the world. It’s slow going, taking millions and millions of years.

Some crash into each other, others scrape edge-to-edge, and still others just sit there, at least for now.

So, Karl says, parts of what’s now Alaska made its way here from someplace else.

“They’re various pieces of other continents. And we have been working very hard over the years to try to figure out which other continent they are tied to,” she says.

Parts of the Southeast Alaska appear to have come from Siberia, and even the Ural Mountains, way on the other side of Asia. Some moved up the coast from points south.

One of those is Baranof Island.

It sits between two long faults in Chatham Strait to the east and the Pacific Ocean’s Fairweather Fault to the west. But about half-way up its eastern side, a separate coastal crack, called the Peril Strait Fault, heads west. That fault separates Baranof from just about everything else in the region.

Geologists know this because they’ve charted the island’s bedrock. Among other discoveries, they found a huge chunk of granite and similar rock in a common formation called a batholith. But, Karl says, part of it is missing.

“That batholith is cut in half, or cut off right in the middle, by the Peril Strait Fault. And the other half of it, in those old rocks, they’re not there at all,” she says.

So, where is it?

Geologists compared its makeup with rocks nearby, then father away, then, much farther away. The closest match was about 1,000 miles down the coast, in western British Columbia.

“The best fit that we have is on Vancouver Island,” Karl says.

Scientists say Baranof’s last contact with Vancouver happened about 50 million years ago.

Another match may be Haida Gwaii, formerly known as the Queen Charlotte Islands. They’re off British Columbia’s coast, about 300 miles to the southeast of Baranof.

Geologist Karl says that means Sitka — and the whole island — made a slow slide up the Pacific Coast. It’s separate from Juneau or Ketchikan or any other part of Alaska.

That knowledge, along with earlier findings, expands our view of the region’s mineral makeup. Practically, that can show where there might be valuable metals, and it could help us understand where where future earthquakes or even volcanoes, might happen.

“Every time you get new data, it just leads to new questions. You might answer one question, but then you have three more. And it just keeps growing and it’s just endlessly fun,” she says.

All of this is part of a larger picture of the region’s complex natural history.

Karl says the map probably couldn’t have happened a few decades ago.

“We have a lot of new technology and we have a lot of new data that has allowed us to understand some things we never knew about before,” she says.

So next time you fly over Baranof Island, or its general neighborhood, take a look at what lies below. The straits, channels and long inlets may show where a fault lies and the Earth’s crust has moved.

In addition to Karl, the map and report credit Peter Haeussler, Glen Himmelberg, Cathy Zumsteg, Paul Layer, Richard Friedman, Sarah Roeske and Lawrence Snee.

Ed Schoenfeld is Regional News Director for CoastAlaska, a consortium of public radio stations in Ketchikan, Juneau, Sitka, Petersburg and Wrangell.

He primarily covers Southeast Alaska regional topics, including the state ferry system, transboundary mining, the Tongass National Forest and Native corporations and issues.

He has also worked as a manager, editor and reporter for the Juneau Empire newspaper and Juneau public radio station KTOO. He’s also reported for commercial station KINY in Juneau and public stations KPFA in Berkley, WYSO in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and WUHY in Philadelphia. He’s lived in Alaska since 1979 and is a contributor to Alaska Public Radio Network newscasts, the Northwest (Public Radio) News Network and National Native News. He is a board member of the Alaska Press Club. Originally from Cleveland, Ohio, he lives in Douglas.