A fermentation specialist stopped in Homer this week. He’s making his way up Alaska, teaching about the crossover among food preservation, microbiology, and community. He taught an intensive fermentation workshop on a local farm.

It’s a sunny day over the Caribou Hills. A group of more than 50 people are milling around a large, green farm, lunch plates piled high with pungent food that saturates the summer breeze.

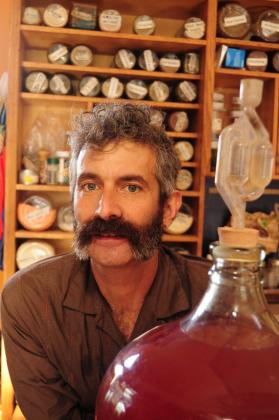

Sandor Katz is sitting on a log near some chickens, wearing a white shirt with a pattern of bright red radishes. He’s the King of Fermentation.

“I ended up being given the nickname Sandorkraut because I was always showing up with sauerkraut and evangelizing about the healing powers of sauerkraut,” says Katz.

Yes, sauerkraut.

“You can make it in dazzlingly bright colors, or contrasting colors, or different sizes and shapes of cutting up your vegetables. It’s actually an incredibly versatile food,” says Katz.

Despite the teasing for always being that guy, the one who brings fermented food to a dinner party, he truly has a deep passion for this process. Through his eyes, the complex world of microorganisms and bacteria at work take on new and beautiful life.

“Before I see anything, like I smell this delicious sourness,” says Katz. “I taste this sourness that speaks to me in this very deep way. What I see is last season’s garden that’s still feeding us and nourishing us. It’s actually never occurred to me that sauerkraut could be ugly.”

And his art is gaining popularity. In the push back against processed and packaged foods, do it yourself preservation methods are picking up steam.

“You know, after a couple of generations of being thrilled to outsource that and enjoying the convenience of one-stop shopping, a lot of people are waking up to the fact that a lot has been lost by severing our connection with producing food and so they’re interested in figuring out how they can play a role in producing their own food,” says Katz.

Charles Meredith, who goes by Chaz, is an active part of the local farmers’ market and independent growing community. He says he’s seen a resurgence of traditional food ways, like canning, pickling, dehydrating, and now, fermenting.

“Well I feel like in rural places in general, the older traditions stick around more and are more appreciated by people in those areas,” says Meredith. “So, I think it’s partially holding onto the past where you can obviously see it slipping away. And also, in a place like Homer, fermentation and things like that are more practical, like he was saying, using it as a means of preservation, in a place where you can only grow vegetables for a third of the year, it’s nice to have a way to have them stick around.”

Like many other people here he’s comfortable with lots of types of food preparation, and of course has tasted pickles and sauerkraut, but still there’s something strangely unfamiliar about fermentation.

Over by the picnic tables, Marcee Gray is scooping up sticky sourdough starter with a spoon.

She finishes packing it into a mason jar, picks up some lunch at the buffet, and settles down in the shade with friends.

“In our culture of course, we do have a little bit of a fear of things like mold and bacteria. And probabl y the nature of it is that it isn’t static, that it does change, that we can’t pin it down and put it in one place and know what it is and where it is,” says Gray.

Marcee’s friend, Mary Lou Kelsey, says she likes the mystery of it.

“I was somebody who asked him, so how do you know what organisms are in there? And if you were really worried about trying to identify all the organisms, it would be difficult because he sort of describes it as a community of organisms. And so, you kind of have to go on that it tastes good and it’s a great mystery,” says Kelsey.

“So, when we’re thinking about fermentation in a practical way, we’re thinking about communities because that’s how microorganisms exist- not singularly but in communities,” says Katz.

That’s kind of like the people who are once again taking an interest in these complex processes.

“You know, if you think of like the baker and the cheesemaker and the sauerkraut maker as some archetypal fermenters- and we can’t forget the beer makers- then these are all products that give rise to exchange and informal barter and economies of community. I think the revival of local food systems is all about building and strengthening community ties,” says Katz.

It can be seen in his own work. He brings people with common interests together, eating communal meals, trading containers of their homemade concoctions, all through his teaching of the art of fermentation…one jar of sauerkraut at a time.