Living witnesses to the forced relocation of West Coast Japanese-Americans during World War II are growing fewer every year. Many who were incarcerated are in their 80s and 90s now.

In the wake of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Roosevelt signed an executive order to summarily round up Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans living along the West Coast.

Their descendants — and historians — want to preserve the memory and lessons from the unjust internment.

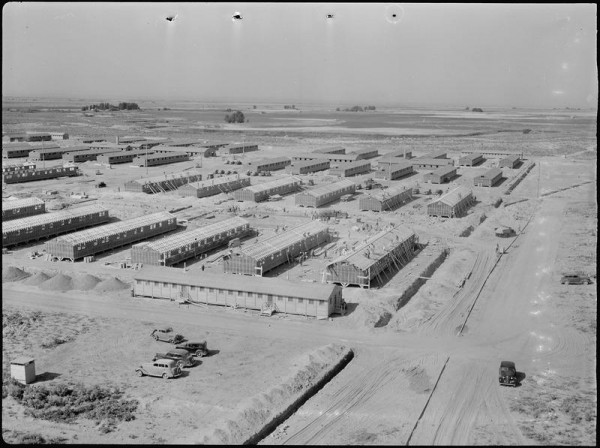

The Minidoka Relocation Center near Twin Falls, Idaho, was one of ten main camps built to confine civilians of Japanese ancestry during the war. It held people from coastal Oregon, Washington and Alaska, most of whom were U.S. citizens.

PHOTO: FRANCIS STEWART, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

At its peak, Minidoka held nearly 10,000 people.

‘It’s not something anyone ever talked about for a while’

The former internment camp is now managed by the National Park Service. It’s also the destination for an annual pilgrimage.

Sam Kito Jr. was five years old when his family was crammed into one room in a barrack block guarded by soldiers amidst the dusty sagebrush of southern Idaho.

On Saturday, he pointed out features inside a former barrack. ”The potbellied stove was in the corner. Then we had a triple bunk on this side,” he said. “And then a double-bunk on this side.”

Kito, 77, hails from southeast Alaska. He said it was his daughter’s idea to join the organized pilgrimage to the site. Hope Kito, 32, is a nurse in Bellingham.

“It was something I always heard about growing up, but it is not something anyone ever talked about for a while,” she said. “I don’t think the magnitude of it was ever expressed. So it was worth coming with him.”

”You can’t rewrite history. You live history the way the cards that were dealt to you and then make sure it doesn’t happen again.”

“When you get new people or younger people involved, what happens is your mind starts thinking about what should have been better for your parents and your generations,” Sam Kito said. “Well, that’s great. But you can’t rewrite history. You live history the way the cards that were dealt to you and then make sure it doesn’t happen again.”

‘We’re afraid of losing those stories’

PHOTO: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Mary Tanaka Abo, 75, was also held at the camp when she was a child. In the midst of war hysteria, her family was “evacuated” — to use the parlance of the day — from Juneau, Alaska.

“Being here made me ashamed of being Japanese when I was young,” she said.

Abo came on the pilgrimage with her daughter and two grandchildren. This was the second trip back for the retired teacher, now living in Bremerton, Washington.

“Just being around people is always good,” Abo said as she fought back a lump in her throat.

”We’re losing the Issei, the first generation, and Nisei, the second generation of Japanese-Americans. We’re afraid of losing those stories.”

Nearly 200 pilgrims journeyed to the site on the final weekend in June. Co-organizer Bif Brigman said this was the 11th edition of the Minidoka Pilgrimage. He said the idea from its genesis carries on today.

“We’re losing the Issei, the first generation, and Nisei, the second generation of Japanese-Americans. We’re afraid of losing those stories,” Brigman said. “That is one of the things that pushes us to do it annually, to keep doing it.”

Brigman said the number of first hand witnesses decreases with every passing year.

“We can see that those memories, those stories are slipping away,” Brigman said.

Preserving memories of a dark chapter in American history

Minidoka National Historic Site Superintendent Judy Geniac also feels the urgency to capture more voices of witnesses before they go silent.

“It would be incredible for us to figure out a way to have young people interviewing, whether it is their great-grandfather or it is their next door neighbor,” she said. “We know that people from the camp went all over the United States after they left the camp.”

Earlier this June, the National Park Service awarded more than $368,000 to the Seattle-based nonprofit Densho, which collects Japanese-American oral histories. The latest grant was directed at enhancing an online encyclopedia about this dark chapter in American history and to help Densho do outreach to connect the Japanese-American incarceration story to contemporary examples of injustice.

Densho curates an online video repository featuring more than 800 interviews about the community’s life before, during and after World War II.

Meanwhile, the physical remains of the Minidoka camp — which nearly disappeared — are being resurrected. A guard tower, barracks, mess hall and fire station have been rebuilt or restored in recent years. Geniac said a visitor center is in the works as are plans to recreate the central baseball field.