The number of wolves on Prince of Wales Island and nearby islands has dropped dramatically, according to a draft report from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

A state official said that decline is something to watch carefully, but he’s not concerned yet about the viability of wolves in that area.

Conservationists, though, are alarmed and say that number could be too low to maintain genetic health among remaining wolves.

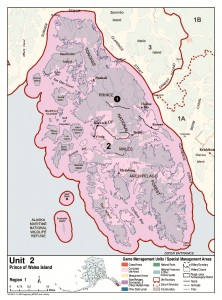

In 2013, the estimated population of wolves in Game Management Unit 2 was 221 animals. A similar study conducted just one year later shows that number dropped to an estimated 89.

Ryan Scott is the Southeast Region Supervisor for Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Wildlife Conservation Division. He stressed that those numbers are estimates based on a small study area on the big island.

“We utilize DNA collected from wolf hair that’s captured in passive hair traps. They roll on it, and we collect the hair and use the follicles to collect the genetic information,” he said.

“We utilize DNA collected from wolf hair that’s captured in passive hair traps. They roll on it, and we collect the hair and use the follicles to collect the genetic information,” he said.

From that information, state biologists determine how many wolves are in the study area, and then use that to estimate the number in the entire game management unit.

Scott said it’s an imprecise tool for such a large area. Prince of Wales Island alone is slightly larger than the State of Delaware.

“We know the conditions are different, we know that the numbers of wolves are different in various places,” he said. “But we do it because by regulation, we have to set a harvest guideline based on a fall population estimate.”

The estimate of 89 wolves is the midpoint of a range. Scott said the population could be as low as 50, or as high as 159.

Despite the lack of precision in the methodology, he said the study does show a clear drop.

“A decline is real, it’s the magnitude of that decline that I think we have to be really careful with,” he said. “It’s going to take additional data collection and additional field work to identify what the trend is.”

State biologists have been studying wolf populations on POW for three years. The first year’s information was not useful, Scott said, because scientists weren’t able to collect enough data. That means there’s only two years’ worth to consider so far.

Scott isn’t overly concerned about the long-term viability of wolves in Game Management Unit 2, and despite the study’s lower population estimate, he anticipates there will be a trapping season this coming winter.

By regulation, the state can allow a total take of up to 20 percent of the estimated population, which in this case would be no more than 18 wolves.

“That number is not set at this point,” he said. “It’s something we are discussing and will be discussing not only internally, but it’s important to have conversations with the trappers, with the communities and subsistence users, the Forest Service. While we know the harvest guideline will be reduced based on regulation, to identify what that number is going to be, there’s a lot of road to travel there yet.”

Larry Edwards is with the Sitka-based Greenpeace office, and he is worried about Prince of Wales Island wolves. He points out that the wolf population study took place last fall, before the winter trapping season.

“The quota for that was 25 wolves. Actually, 29 were taken,” he said. “So, the number now is surely lower than what was reported.”

Edwards said the genetic health of the remaining wolves needs to be considered when determining the population’s future viability.

He gives an example of a group of wolves on an isolated island in the Midwest’s Lake Superior. That group had low numbers for many years, and people thought it was stable.

“There’s recent reports and science that’s come out on that, that the population has crashed,” he said. “There’s only three wolves left there, and those wolves are in very poor health because of inbreeding. So, once you get to a small population, you need to be concerned about inbreeding.”

Edwards said his group will review the official Alaska Department of Fish and Game study once it’s released. But, based on information available so far, he said Greenpeace likely will ask for an emergency closure of wolf trapping in Game Management Unit 2.

“And that would involve both Fish and Game and the Federal Subsistence Board,” he said.

Subsistence hunting is managed separately by the federal government, but often in cooperation with state agencies.

Greenpeace and other groups filed a petition in 2011 to get the Alexander Archipelago wolf protected under the federal Endangered Species Act. Edwards said that petition is still under review.

Conservation groups say logging and activity related to logging – such as building roads – has led to the decline of wolves on Prince of Wales Island, partly because more roads provides easier access for hunting and trapping.

Edwards said information from the state’s wolf population study likely will be used in future challenges to old-growth logging on POW.

At deadline Wednesday, the state had not yet released the official wolf population study for Game Management Unit 2. It is expected to be published within the next few days.