In the winter, in the late fifties and early sixties, when construction season in Anchorage was dead and Dad grew bored with painting landscapes, he got out his tripod and the black Graphlex he’d bought at Stewart’s Photo on Fourth Avenue.

The large box-like camera looked like those used by professional photographers, maybe for Life Magazine. It had cost twice Mom’s monthly salary and, for a few weeks, dark looks and strained silences filled our small house on Tudor Road.

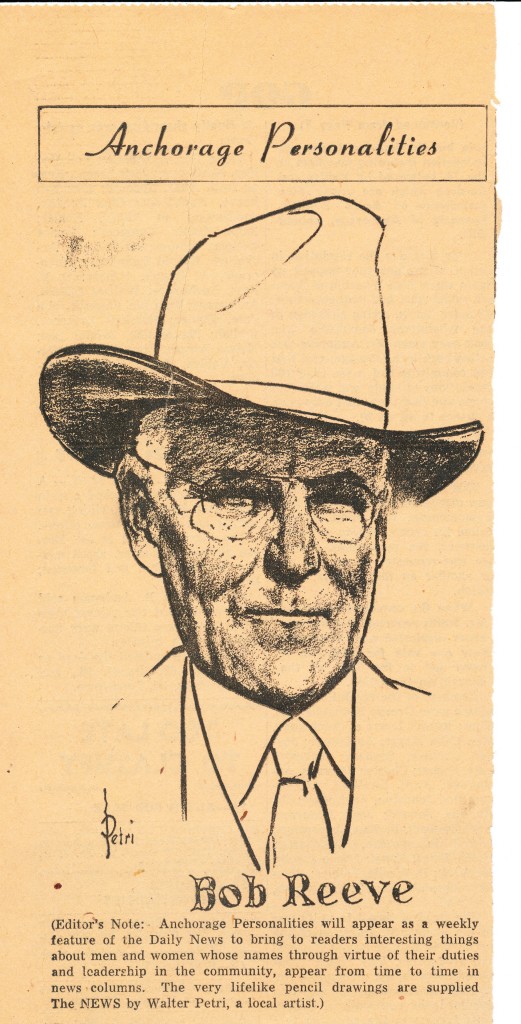

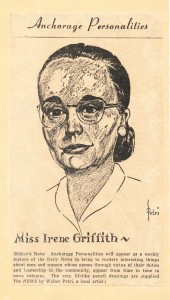

Dad set up appointments. Then, with his hat at a rakish tilt, he’d drive to offices or homes of his clients and set up his tripod. Using the bulky camera, he took portrait photographs of, among others, the head of the carpenters’ union, Irene Griffith, the town’s librarian, Bob Reeve of Reeve Aleutian Airways, and Ora Dee Clark, a noted teacher who left me $250 in coins in her will for my college fund. Later, Dad drew portraits from the photographs in charcoal.

He converted our tiny bathroom into a dark room with a built-in fold-down table and, with the house reeking of developer, turned out black and white photographs. I liked the ammonia smell; it told me something was happening. Mom, having come to grips with the price of the Graphlix, didn’t complain. “At least he doesn’t drink,” she told friends.

Dad didn’t charge for the photographs or the portraits he made from them, some of which appeared in the Daily News and Anchorage Daily Times. When I asked why he didn’t ask to be paid, he said, “Nah, I’m flattered they’ll sit for me.”

Nor was he interested in opening a photography studio. “What photographer in Anchorage is making any money?” The few he knew were hanging on by their fingernails. I knew he wanted to stop pounding nails for a living. He was tired of the twelve-hour days, seven days a week that came with the short construction season. He wanted to explore other possibilities for work.

Even if professional photography wasn’t in his cards, I could tell from his smile that he enjoyed those moments when he talked to people, took their photographs and carried an important looking camera.

They are all gone now, including Dad. Yet, I think about those times and I imagine the people who sat for him must have felt a brief, even heightened moment of specialness when the focus was on them.

As for Dad, he also had a heightened moment, a moment when he was not a carpenter, but an artist, respected and in command when the flashbulb went off.

Read more snapshots from Jan on the Growing up Anchorage blog:

www.growingupanchorage.com

Jan (Petri) Harper Haines was born in Sitka, Alaska and is Athabascan, Irish and Russian. In 1990 she began gathering the stories told by her mother and grandmother about their lives on the Yukon. Her book "Cold River Spirits" grew out of these early stories. Jan’s short stories have appeared in literary publications and magazines. She is a graduate of Anchorage High School (West), and earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks. She is a former secondary education teacher, and had a twenty-year career in advertising and marketing.

Jan lives in Marin County, California with her husband, and often visits Alaska.