OceansAlaska Marine Science Center completed its first season of operation this year, successfully producing hundreds of thousands of shellfish seed.

Barbara Morgan, research and training specialist, said the first year was successful enough that the Ketchikan-based center is expanding operations.

“This next season, we intend to produce between 5 and 10 million oyster seed and about 100,000 geoduck seed for oyster and geoduck farmers in Alaska,” she said. “This year, we ended up with 300,000 oyster seed, which seems like a lot, but demand is in the millions. In Alaska. Not only is the demand really big in Alaska, we were receiving calls from BC, Washington, Oregon and as far south as southern California.”

Rodger Painter of the Alaska Shellfish Growers Association agrees there’s a seed shortage.

“We estimate the industry got about 40 percent of what it needed this year, and last year, the figure was at 48 percent,” he said.

Painter said the expanded production next year should meet the current demand. There is one other shellfish hatchery in Alaska, Alutiiq Pride in Seward. That facility, too, plans to expand.

The shortage appears to be the result of ocean acidification. OceansAlaska will continue with seed production at its current facility for at least one more season, to help satisfy demand in Alaska alone. But, Morgan said, it won’t be enough.

“Demand is growing, the mariculture industry, it wants to grow,” she said. “It’s at a tipping point right now. Either it grows, and gets past the seed shortage issue, or it may tip back, and we don’t want it to tip back. We would actually like to build a bigger facility, three or four times bigger.”

The planned new facility would produce up to 50 million oyster seed, and a million geoduck

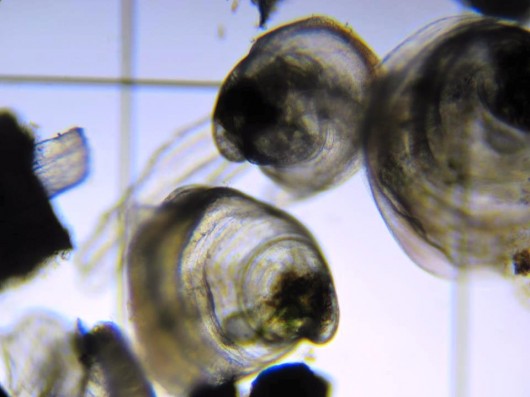

This OceansAlaska photo shows geoduck seeds.

seed for Alaska shellfish farmers. Morgan said that industry has big potential, especially for people in small coastal communities.

“It’s a great economic development potential, here in Southeast Alaska, in particular,” she said. “Small communities, out in the middle of nowhere, I’m from one so I can say that. I grew up in Edna Bay. So, Naukati, Coffman Cove, a lot of small places have oyster farms around them already, but they need the support to really grow, and this could actually be the economic support for those small communities that are kind of in an economic slump right now.”

Painter said there are 75 permits for shellfish farms in Alaska, but only about 25 of those are active. Of the active permits, about 15 are in Southeast.

“But there are a number of additional farms in Southeast that aren’t selling yet, but have animals in the water and are moving in that direction,” he said.

For example, Hoonah and Angoon are developing new oyster farms. Painter said they, and others, all will need seed.

Morgan described how Oceans Alaska grows oyster seed, or spat. It’s complex, and starts with a pile of fertilized shellfish eggs, purchased from Outside.

“The life stages of the oyster is that, after fertilization, they develop into a free-swimming larva stage,” she said. “They can be transported pretty easily at that point. We get those from a company in Washington, Coast Seafoods. They ship them up. They look like a big ball of wet sand.”

The larva are put into a tank, where they swim around for a while eating algae, which Morgan grows at the facility. Then the tiny oysters want to set on something. OceansAlaska crews grind up oyster shell and put it on the bottom of the tanks. That provides an anchor for developing oysters.

“It looks like sand on top of sand to the naked eye,” she said. “You need to use a microscope at that point to see that there is actually something going on.”

The microscopic oysters form their own shells, continue eating Morgan’s high-quality algae, and grow.

“At about 2 mm, the naked eye can see that there is actually something going on, and when we ship them out at 5 mm you can see that they are teeny little oysters at that point,” she said/

Oyster farmers in Southeast can “plant” their seeds in the fall, because the water doesn’t get too cold. The seed won’t grow fast over winter, but once it warms up, the tiny shellfish can feed on algae blooms.

Depending on the species, oysters need two to four years before the first harvest.