Nunam Iqua , in the Yup’ik language, means the “land’s end” – a place on the Bering Sea coast that is so flat it’s hard to tell where the land meets the sea. But when it comes to spelling, this community stands tall.

Once again, the champion for this year’s statewide Yup’ik Spelling Bee hails from Nunam Iqua. In the 12 years of competition, it was one of the first communities to participate.

This year’s tournament, on April 13, was held at the University of Alaska Anchorage at the home of the Alaska Native Science and Engineering Acceleration Program. The site is symbolic because it gives high-school students a leg up on earning a college degree, and also incorporates Native language and culture.

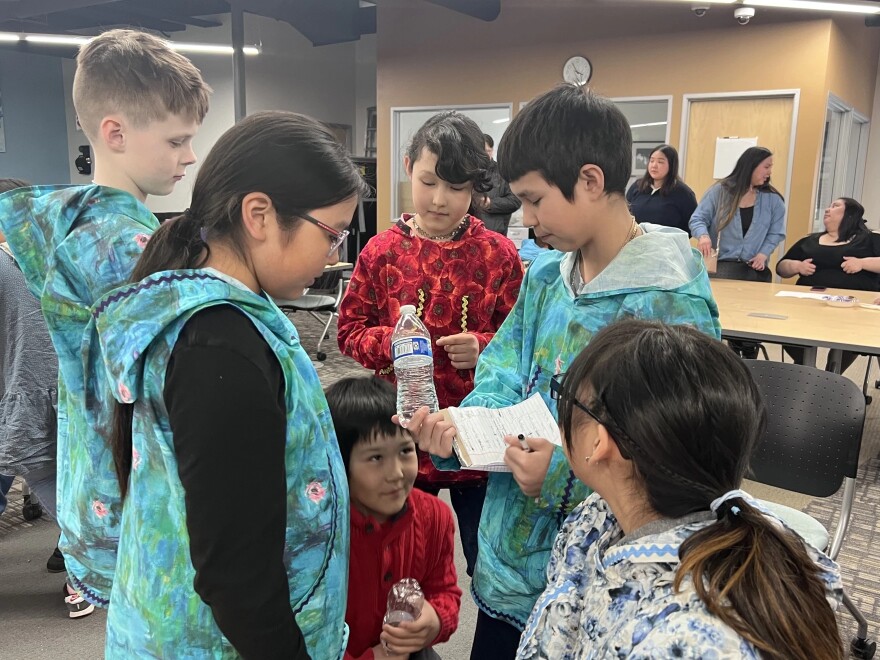

Families and coaches streamed into the building to fill about 50 seats, along with students from nine school districts across the state.

“Please keep to yourselves and be quiet,” said one of the judges, as the Yup’ik competition got underway.

Spelling bees aren’t necessarily the best of spectator sports, but the silence in the room doesn’t mean there’s no excitement.

“I’m happy for the students. Nervous at the same time, and I have butterflies in my stomach,” Marina Barner whispered.

Although she can’t cheer out loud, Barner came to support a student from Bethel. And like everyone else in the, room, she understands that quiet is necessary to help the students concentrate. But the sense of pride that families feel, speaks volumes.

“To be here, to be watching my daughter. I cannot express how it makes me feel,” Thomas Carl said. “I am proud of her.”

Carl is from Toksook Bay, a village where the Yup’ik language, or Yugtun, is still strong. But he married into a family in Akiak, on the upper Kuskokwim River, where the language struggles to survive.

Carl’s daughter Megan is only a fifth grader, but like the many of the kids here, she’s a shining star of hope in her community to keep Yugtun alive.

Despite her young age, she’s finished close to the top in the past two years. Each time the competition grows.

The 2024 Yup’ik Spelling Bee drew 21 students from five districts and eight schools. The Lower Yukon School District added two new teams, in addition to the one at its award-winning Nunam Iqua school.

“Well, we saw the benefits,” said Janet Johnson, who directs language and culture programs for the district, which has seen gains in Nunam Iqua test scores for language and reading.

It’s not clear if there’s a direct correlation, but Johnson says there's a noticeable difference in the Nunam Iqua students.

“They were becoming stronger in their identities,” Johnson said.

She says pride in culture seems to fuel their desire to learn to read and write in Yugtun, something that isn’t easy when you consider that until about 60 years ago, the language was almost never written, only spoken—and had to borrow from an English alphabet that is poorly suited for the sounds of Yugtun.

Essie Beck, in her job as principal at the Alakanuk school, sees firsthand why spelling in Yugtun doesn’t come naturally and takes more work to master.

Although Beck is originally from Alabama, she’s learned quite a few words – and her son, Kian, now in the fifth grade, has taken Yup’ik language classes since he was small. Kian's pronunciation is very authentic, and he says learning Yup'ik has helped him make friends and be a part helps of the culture. But after watching his progress, his mother says she can vouch for the difficulty of learning to spell in Yugtun, compared to English.

“Oh, harder words,” she says, that go beyond a simple alphabet to represent the sounds. “The apostrophes, the dashes, the brackets, everything. It’s a lot more challenging.”

During the competition, Pinlinguasta Brennan Paje, a seventh grader from Stebbins, asked a judge for clarification before spelling a word. A number of students before him were very close but missed one thing.

“What do you call that curve on top of the letter?” he asked.

The curve is called a ligature, which designates how two letters are combined to produce a sound that’s not in English.

Brennan won the round, after he included the word “ligature” when he spelled it out. The word also had an apostrophe, something the other contestants had missed.

There’s another big challenge. Although English has a few extremely long words, like “antidisestablishmentarianism,” Yugtun has a lot more. That’s because it’s a polysynthetnic language, a term for languages in which one word can be used to make a complete sentence.

For example, there’s “angyangqertuq,” which means “He has a boat.”

Often it would take about six to eight tries for contestants to arrive at the correct spelling. The judge would say “Assirtuq” to signal that the speller had the right answer.

Assirtuq means “It’s good.” And even though Ian Agayar, a seventh grader from Alakanuk didn’t hear “assirtuq” very much, he still feels like a winner.

“You get to learn new things. Period,” he said. “It’s a new experience to everybody.”

Nunam Iqua’s principal, Samantha Afcan, says the students involved in the program learn to be persistent.

“They’re awesome. The way their brains can connect it,” she said.

Last year, Nunam Iqua swept the top three places in the spelling bee, but this year they won two. Kirstin Manumik, a seventh grader, won the championship and Jaylynn Strongheart, a fifth grader, finished third.

They spent hours and hours every week to prepare for the competition. One of the benefits was a trip to Anchorage, an exciting change of pace for students who live in a land where there’s not so much as a hill.

“You should hear the kids while driving around,” Afcan said. “'Oh, look at that car. Oh, look at that truck. Look at that tree.'”

A group of Native language students from the University of Alaska Fairbanks were on hand to provide support. They also performed dances to help students relax during the breaks, including a crowd-pleaser called the Polar Bear Shake.

While the Yup’ik competition has had a steady supply of competitors, the Inupiaq spelling bee is still slow to catch on. Only two students from Sitka competed, but those students got most of their words correct. Organizers hope that in time, the Inupiaq bee will draw more interest.