The first time the state tested for PFAS in Yakutat’s groundwater, it found contamination in a cluster of wells around the airport.

One of them exceeded the state’s standard for drinking water and that property is now being supplied bottled water.

That’s because PFAS is a group of bio-accumulating chemicals linked to serious health problems including cancer. For decades, they’ve been produced for commercial and industrial applications from non-stick cookware to fire-retardant foam used at airports.

A second round of testing in June expanded the survey: the same 14 wells were tested, plus seven more. But this time none of the wells exceeded the state’s safety threshold for PFAS.

A cleanup effort is still likely years away. So what changed in the months between tests?

“Basically, they’re changing the test so that it will pass and it’s very disappointing,” said Yakutat City Manager Jon Erickson.

He’s a former school administrator. So he knows something about standardized testing.

The EPA recommends testing for more than a dozen different PFAS compounds. Which is what the Department of Environmental Conservation did when it first tested in Yakutat back in February.

But in the months between the two tests, Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s administration directed DEC to change its regulations.

It now screens for two PFAS compounds rather than five when determining whether water is safe to drink — a move that led to internal criticism from some of its own scientific staff.

DEC Commissioner Jason Brune told CoastAlaska that the revised regulations are designed to bring Alaska in line with the federal government’s standard until there’s more known about the problem.

“We are following the lead of the EPA on the new testing that we are doing,” Brune said, “and the EPA has identified PFOS and PFOA as the ones that have lifetime health advisories.”

By limiting its testing to just two compounds, the DEC is no longer screening for others — such as PFHxS — which in February had been one of the drivers for declaring a Yakutat drinking water source contaminated.

“Which is really incredible,” said David Andrews. a chemist with Environmental Working Group in Washington D.C. The nonprofit is pushing for stronger PFAS cleanup efforts nationwide.

“Because, the rest of the country has moved to testing methodology that allows you to detect more of these PFAS compounds,” he said.

Andrews says while some states don’t regulate PFAS at all, he’s not aware of any that have rolled back existing standards like Alaska has.

“It is striking and concerning that the state is moving the opposite direction,” Andrews said. “Both with respect to the standards as well as with respect to testing and disclosure of contaminants.”

PFAS contamination is a nationwide problem that is emerging as a major health concern as plumes are detected around factories, military bases and near airports where firefighting foams made with PFAS compounds are used.

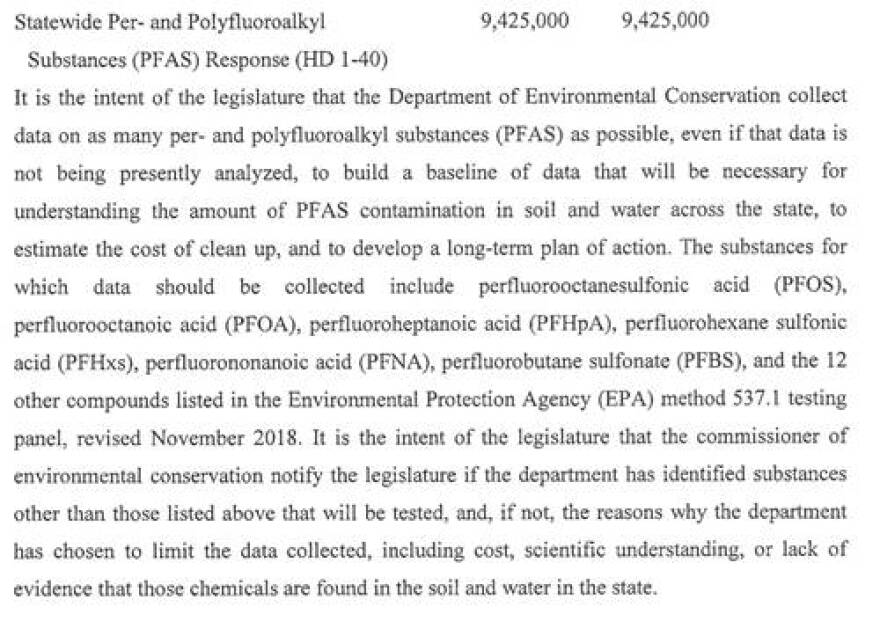

This year, Alaska’s legislature appropriated $9.4 million to DEC to deal with PFAS contamination. And attached to the money came specific instructions for the agency to test for at least 18 PFAS compounds, even if it’s now just regulating for two: PFOS and PFOA.

“Getting the data collected is the first step in understanding the extent of the problem,” said Rep. Geran Tarr (D-Anchorage), who co-chairs the House Resources Committee.

She says if DEC ignores the legislature’s intent, it could invite a lawsuit from a third party like an environmental group.

“Because at this point, they are violating the law that we just passed,” Tarr said.

DEC Commissioner Jason Brune says the legislature’s budget language is still being analyzed.

“We’re planning on having that discussion internally,” he said.

Internal emails released under a records request show DEC’s PFAS response was directed in part by Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s top political staff.

Brune defended his agency’s record.

“Since the Dunleavy administration came on December 3, we have done more testing, we are providing more drinking water, and we are absolutely paying attention to this issue,” Brune said.

Back in Yakutat, City Manager Jon Erickson says there are lingering concerns for wells around the state-owned airport. He’d like to see the state assist by extending the city’s municipal water supply.

“We have really good water,” Erickson said by phone. “In fact, that is my hope is that the state will come to its senses and say, ‘Hey let’s hook into the city water supply four miles away’ and save the people out there at the airport.”

As it stands, the state is still supplying one property with bottled water: it’s grandfathered in.

But whether any of the other wells included in the second round of test would’ve been considered fit to drink under the previous standard remains unknown.